Editor's note: This section contains graphic images and descriptions and may not be suitable for all readers.

Arizona's border is a desert of death.

Nearly 2,000 men, women and children have died trying to cross the border illegally in the past decade - not counting the bodies still out there, waiting to be discovered.

A decrease in illegal crossings over the past six years hasn't slowed the deaths, steady at about 200 annually. This year could be the worst yet.

The deaths surged after a mid-1990s security push beefed up enforcement in Texas and California. Authorities expected Southern Arizona's harsh desert and deadly heat to be a natural deterrent from crossing.

It wasn't.

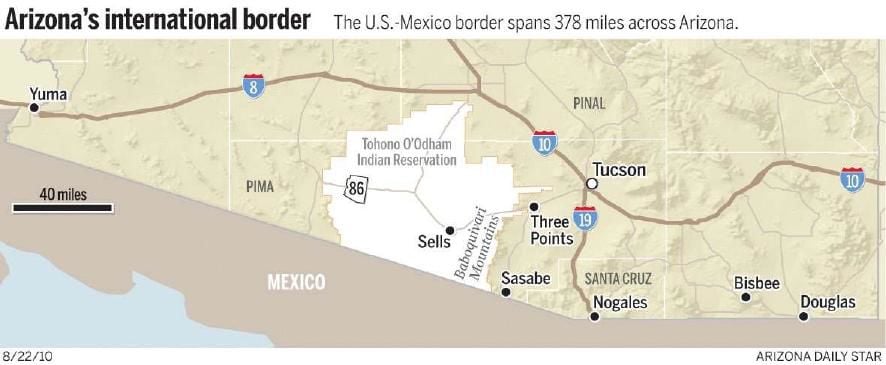

Arizona became the busiest stretch of the border, and a massive buildup of agents, fences and technology followed. That prompted smugglers to lead crossers through ever-more-remote terrain to avoid detection, making the trek more deadly.

Most bodies end up here, at the Pima County Medical Examiner's Office. The onslaught has transformed the jobs of the forensic-science staff, especially during the scorching summer months when illegal border crossers are found dead almost daily. The office has handled 1,700 bodies in the past decade - 81 this past June and July.

Border crossers make up about 20 percent of the exams done in this office that serves a county of more than 1 million people. But especially in summer, they take up a big chunk of the staff's time. Field agents drive for hours to pick up bodies in remote reaches of the desert. Investigators take fingerprints, snap photos and coordinate with law enforcement and foreign consulates.

It's difficult - and harrowing - work because people found dead in the desert are often robbed of all distinguishing features by searing sunshine and scavenging animals. On top of that, Mexican border crossers commonly die without identification - smugglers tell them not to carry it. And illegal crossers from other countries often carry fake Mexican IDs so if caught they'll be deported just across the border to Nogales, where they can try again.

The lack of ID turns cases into mysteries that require doctors to be part pathologist and part investigator, spending nearly as long looking for clues to the person's identity as determining the cause of death. The office's only anthropologist spends most of his time on them, taking DNA samples and analyzing pelvic bones, skulls and femurs.

People have died along the U.S.- Mexico border for decades, but no medical examiner's office has dealt with this many, for this long.

There's a cost to taxpayers, too, although it's tough to say exactly how much. Recoveries, autopsies and investigations are blended with the rest of the county-funded office's work. But each autopsy runs about $2,000, and the office did 194 last year. That adds up to $388,0000, 13 percent of its budget.

To handle all the bodies, the county hired an additional doctor and a full-time anthropologist and paid $350,000 for a second storage cooler. The office also gets state and federal money, like $60,000 in Homeland Security funds that bought a refrigerated trailer to store bodies during busy summers like this one.

For the 27-person office - which gets every crosser found in Pima, Santa Cruz and Pinal counties - there's never enough time and never enough answers. But they share a common goal: They will ensure that the dead go home.

"We treat people like we would want our family members to be treated," says Dr. Bruce Parks, the chief medical examiner since 1991.

The staff's stories - and those of the people brought to the office in bags - embody what has become the one constant along Arizona's stretch of border: death.

"The names change, the location maybe gets a little more remote as the years go on," says Bruce Anderson, the office's forensic anthropologist. "But it's the same story."

Field Agent Ron Foster examines the belongings of an unidentified border crosser, case no. 10-1227, at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner on June 22, 2010.

DAY 1: 10-1227, John Doe

A soiled brown backpack rests on a white body bag.

Both sit on a gurney Field Agent Ron Foster unloads from his SUV and wheels into a receiving room at the Medical Examiner's Office.

Foster's faded black cap lies low on his head, covering his eyes. It's discolored with dirt, but the yellow words remain clear: "Pima County" in lowercase above "Medical Examiner" in uppercase. It looks like it's been on his head for every one of his desert body-recovery trips over 19 years.

One by one, he takes items from the backpack and sets them on a white sheet. Brown pants, a brown jacket, four Mexican peso bills that add up to about $15, two bus passes, a hotel receipt, boots, a torn piece of paper with scribbled phone numbers, and a prayer card with the picture of Pope John Paul II.

The backpack was on the ground near the man inside the body bag - the 1,587th illegal border crosser to end up here since 2001.

THE HANDOFF: As the sun rises, Trevis Hairston, a field agent with the Pima County Medical Examiner's Office, left, picks up a body from a sheriff's deputy. Hairston has been up much of the night - common for field agents during the summer, when they often get a new body a day. "Sometimes at night I don't know how I do it," he says. "I eat a lot of sunflower seeds out there."

A Border Patrol agent found him on the Tohono O'odham Nation. Foster picked him up at the police station in Sells and now investigators will try to figure out how he died and who he is.

Until they make that determination - if they ever do - he'll be Case No. 10-1227, John Doe.

He's the first of seven illegal border crossers brought here this week. As is the case with most who arrive during the summer, the cause of death is hyperthermia, or an extremely high body temperature.

This is the busy season for the office, just 60 miles north of the busiest and deadliest stretch of border. Today is the eighth of 19 straight days with temperatures at 100 degrees or hotter.

Trekking across Arizona's desert is always treacherous, but the heat makes it lethal, leaving no margin of error for those who run out of water, or get lost or left behind.

Death out there is painful and grisly. As the body temperature climbs as high as 108 degrees, muscles rot, blood vessels dilate and the water-starved heart beats ever faster, doing all it can to compensate for the reduced volume of blood. Cramps come first, then weakness, nausea, fainting. Finally the mind betrays the body, leading to disorientation or hallucinations.

Phone numbers, peso bills

Investigator David Valenzuela comes in, joins Foster at the still-closed body bag and leafs through a worn black wallet. For nine years, Valenzuela was a field agent like Foster.

Six months ago, "Sarge," as his colleagues call him, was promoted to investigator in charge of piecing together the identity puzzles.

"Was this on him, Ron?" Valenzuela asks Foster.

"I think it was probably in the bag because I don't think it has any fluid on it," Foster answers. Then: "He's got some peso bills."

"Phone numbers," Valenzuela says.

"Calling card," Foster says.

Just then, Field Agent Tessa Lee asks for help moving a heavy bag that belongs to another dead border crosser. Interruptions like this are frequent: With so much to be done, it's rare to complete one task before being hit with the next.

Forensic Medical Investigator David Valenzuela looks through the wallet of a unidentified border crosser, case no. 10-1227, at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner on June 21, 2010.

Clues from bus tickets

Valenzuela turns back to the new arrival, looking at bus tickets found in his wallet.

"He started out in Culiacan. This was on May 26. And he had another one in here for Jalisco."

"In the End" from metal/rap band Linkin Park plays in the background as Lee and Pathologist Assistant Nina Kniffin catalog the belongings of another border crosser across the room. Conversations overlap.

"A man's black belt," Kniffin says. "A man's socks, white."

"Yeah, Guadalajara, Jalisco," Valenzuela says.

"One black wallet," Kniffin says. "Blue shirt."

"So, is he clothed, then?" Valenzuela asks Foster.

"Uh, yes."

Valenzuela partially unzips the body bag. He holds it open, squinting a little at the man's face.

The eye sockets are hollow. The right part of his jaw is exposed. There's black hair with a bit of white on his chin and head.

Valenzuela unzips the rest of the bag. Beetles scuttle across the man's sunken stomach. His hands are black, frozen in a half-clench.

The stench of decomposition permeates the room. It's not the odor of clean death found in a funeral home, but a breath-stopping stench like meat left outside during an Arizona summer - but worse.

"You don't get used to it," Field Agent Trevis Hairston says. "You just tolerate it."

"Soiled shirt," Foster continues as he digs through the man's pockets.

"I don't see any tattoos," Valenzuela observes.

"Black pants, black belt. He was off-trail in the desert under a tree."

"Did they say that it looked like he lay there or was he placed there?"

"They didn't say. Probably lay there because of the way his legs were."

"This could be like an older gentleman," Valenzuela says. "He's got white hair."

"So do you," Foster retorts.

"I'm old," Valenzuela says, laughing.

After their inspection, Lee and Foster wheel the body into the cooler.

It's 103 degrees outside, probably hotter on the Tohono O'odham Reservation where this man died. The temperature inside the cooler: 37 degrees.

A body shipped for burial

When the Medical Examiner's Office has exhausted all options for identification or finding relatives, it turns bodies over to the public fiduciary in the county where they were found.

That's why Micah Powell of J. Warren Funeral Services in Casa Grande is here today.

Victor Valencia-Valencia died on April 27, 2008, when a pickup he was traveling in with 30 other illegal immigrants crashed and rolled northwest of Tucson in Pinal County. He was one of four who died.

Investigators were able to identify him, but they never found his family. After two years inside the crowded storage cooler, it's time for him to leave.

"If there is no family, there is nobody to ship him to," Lee says.

His body is in bad shape, and the three decide to lift the double-bag and add a third. Dark red fluid splashes onto the floor.

When they're finished, Powell drapes a decorative red blanket over the body and wheels it to his van.

Valencia-Valencia, 19 when he died, will be buried the next day in a pauper's grave. He'll get a small headstone with his name on it. A volunteer minister will lead a short graveside ceremony with a couple of mortuary workers standing by.

REHYDRATION: Krystal Poulin fingerprints an unidentified woman's severed hand, which first had to be soaked because it was so mummified. Nobody likes having to cut off the hands, but it's the only way to still get prints, which is key to figuring out who a person is.

TAKing fingerprints

Investigator Gene Hernandez slides a bucket across the counter.

He lifts the lid and pulls out a slender, discolored hand. It's severed at the wrist.

The hand came from a woman who looks to be in her 30s, found badly decomposed on the Tohono O'odham Reservation the week before. Investigators don't have any good leads on who she is, which is why her hands have been soaking in a pink fluid called sodium hydroxide.

Rehydration gives investigators a chance to get decent prints from people whose hands have mummified. When it works, they send them to law enforcement in hopes of finding a match.

Under Arizona's blistering sun, finger and toes start to harden within a day or two, as they turn purple or black. The heat speeds up the decomposition of the rest of the body, too, causing rapid bloating, blistering and splitting of the skin.

Investigators also use this rehydration process on cut-out sections of skin with tattoos they need to get a better look at.

Nobody likes having to cut the hands off of the body, but it's the best way to fully submerge them in the liquid. Getting good prints can often lead to identification - and answers for frantic families, the ultimate goal.

With a towel around the palm, Hernandez stretches each finger backwards. Then he leaves the towel-wrapped hands to dry, the critical step in this process. Through trial and error, Hernandez and others found that wet hands make for smudgy and slippery prints, but dry ones print neatly.

Hernandez is comfortable in this small room behind the exam area - he worked as a pathologist assistant for four years before becoming an investigator in 2004. He started working at Tucson's University Medical Center at 19 years old and got hooked on forensic science.

A few years ago, Hernandez saw a Discovery Channel program about a forensic scientist who had developed a way to fingerprint mummified hands. He called and arranged to visit him in Los Angeles and learn a micro-seal technique that creates a mold of the finger, which is then printed. He recently used the technique successfully for the first time on a decomposed border crosser whose fingers were so mummified that even rehydration wasn't enough.

DAY 2: Inside a boot, a clue

"Pásale, pásale," Investigator Hernandez says, welcoming Lorenia Ton and Laura Ruiz of the Mexican Consulate in Tucson with a kiss on the cheek. "Come in, come in."

Ton and Ruiz are here for updates on cases they are following and to review new arrivals. Investigators work closely with the consulate for help calling phone numbers found on bodies and getting identification documents, pictures and DNA samples from family members. Some of the dead come from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, but most are Mexicans.

The clickety-clack of Ton's high heels resonates as Hernandez leads the women from one building to the other.

The north building is for bodies, the south for offices. The cloud of death shadows everything here, but the separation draws a clear line between the dirty work and the clerical work.

Hernandez and Ton have a bit of both to take care of today. The dirty work comes first.

Hernandez leads them into the room where bodies are brought upon arrival and heads over to four dry-erase boards with grids for each box representing a spot in the cooler.

In 2006, a second permanent cooler was added, giving the office space for 220 bodies - more if they are skeletonized. Both coolers are nearly full.

The office also owns a 55-foot-refrigerated trailer it bought in 2005 with a state Homeland Security grant. It holds 25 bodies when needed, as it is this summer.

Hernandez brings out the body found the day before, which is set for an autopsy this morning. "He was found by Border Patrol, looks like three miles south of 86," Hernandez says of the highway that crosses the Tohono O'odham Nation.

Ton and Ruiz untie a biohazard plastic bag with the man's belongings. Ruiz examines a brown boot and pulls out the sole.

Bingo: a Honduran ID card for Manuel Vargas Salvidar, age 36.

"We've got to make sure it's not falsified and that it's a legit ID card, but at least we have kind of a direction in which to start," Hernandez says.

Next, he brings out the body of the woman whose hands have been cut off. He turns over a thin red belt she was wearing and inspects it for a name, initials or a phone number. He rips open a sewn cuff on the jeans.

"Sometimes you'll find something in there," he says.

From another room he brings things found on the woman: a small ring, a 50-peso bill, lip balm and a small tin of menthol.

"This might be something that we can use," Hernandez says. "The family might say, 'Hey yeah, she always wore this little ring' or something, you know?"

Ton holds up the menthol, likely used to treat blisters, and notices tiny letters that read, in Spanish, "Made in Guatemala."

Ton tells Hernandez the Guatemalan Consulate in Phoenix is looking for a woman who has been reported missing. They agree to e-mail photos.

One step forward, two back

Sometimes what looks like a promising lead turns into a disappointment.

Hernandez, Ton and Ruiz are excited to tell Investigator Valenzuela about the Honduran ID card they found in the boot. It's Valenzuela's case.

"Were those boots on him?" Hernandez asks Valenzuela.

"No, they found them away from the body."

"So, those might not even be his boots?"

"They don't think that's his wallet, either," Valenzuela says, "because none of that was close to him, really.

"Ron (Field Agent Ron Foster) said he couldn't see why he would take his boots off because it was too hot out there to be barefoot," Valenzuela says. "But you know, once you start going delirious, you just take off all your clothes out there."

MAP OF THE MORGUE: Forensic medical investigator Gene Hernandez searches a dry-erase board for the location in the morgue of an unidentified border crosser. Each box on the four grids represents a spot in the cooler. Border crossers are outlined in blue.

Prints match, but don't

Ton moves to Investigator Dave Thompson's desk to discuss a man found June 8 on the Tohono O'odham Nation.

They found an ID card on him and Ton located a family in Phoenix. But the body was so decomposed the family couldn't identify him by photo. The Border Patrol found prints for a man with the same first and last names but they don't match those from the Medical Examiner's Office.

Ton knows why. The family told her the missing man has a cousin with the same first and last names who has been apprehended by the Border Patrol. That's why the Medical Examiner's prints don't match the Border Patrol's.

It's a difficult case, but these investigations are what prompted Thompson to take the job in January. He worked as a Pima County Sheriff detective for 12 years before an injury forced him to retire, and he missed the action.

Thompson tells Ton he plans to resubmit fingerprints to the Border Patrol with the new information. If that doesn't work, investigators will take DNA samples from the family and compare them with DNA from the body, a process that usually takes months.

"TWINGE OF EMOTION"

It's about 1:30 p.m and Parks, the chief medical examiner, has just begun an autopsy scheduled for first thing this morning.

It was pushed back so he could examine a 27-year-old man stabbed to death the day before at a Tucson apartment.

The office performs autopsies or external exams on about 2,000 bodies a year. Homicides generally take precedence.

Holding an audio recorder, Parks stands over a gurney with belongings recovered near the man found the day before on the Tohono O'odham Nation. He looks closely at two bus tickets found in a wallet.

Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Bruce Parks speaks into a recorder during the external exam of an autopsy of an unidentified border crosser, case no. 10-1227, at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner on June 23, 2010.

One is dated May 24, from Mexico Norte to Jilotepec. The other is from May 26 from Culiacan to Tijuana.

"On one of the receipts is the name Ernesto Nogueda," says Parks, speaking into the recorder. "N-o-g-u-e-d-a."

There's a May 27 hotel receipt with the same name but no location.

"Multiple numbers are printed on the back of the hotel receipt," Parks says into the recorder.

Next, he grabs the boots.

"Brown boots, LA Gear brand, U.S. size 9. … Within one of the boots is a national registration card from Honduras with the name of Manuel Vargas Saldivar. S-a-l-d-i-v-a-r.

"One pair of gray socks, each bearing U-S-A on the sock cuff. Next, one pair of light-colored, perhaps light gray, Lee brand denim pants. The pants are perhaps size 38-30."

After the exam, the clothes will be machine-washed so investigators can better read sizes and any marks that could help identify the wearer.

Parks picks away the frayed pieces of what once was an undershirt. He examines hair on the man's chin and skull. He holds the boots up to the man's feet. They look too big, but feet can shrink during decomposition.

Parks grew up in Nogales, Ariz., the son of a customs inspector. He attended medical school at the University of Arizona, where he was drawn to forensic science. He wasn't sure at first he could deal with the dead but he soon found the key: distancing himself from their human characteristics.

"You get a little twinge of emotion with these deaths but you can't focus on that," he says. "You would be consumed with grief."

He became chief examiner four years after he was hired. He's been the soft-spoken and calm voice of the office ever since.

The door opens and a tall man with streaked blond hair walks over to the body. He leans over the man's face, his hands behind his back. Then he turns to the belongings.

This is Bruce Anderson, the key to solving many of these cases. The office anthropologist for the last decade, Anderson gets involved if there's a question about identify, which there is about half the time.

"There's two different names," Parks tells him. "There is a name on the ID in the pants and there is a name on some bus receipts."

"I'll ask Robin to run both," says Anderson in a deep voice made for radio.

Robin Reineke is a University of Arizona anthropology graduate student who has worked here for four years, trying to match missing-persons reports with bodies.

As is common in summer, the cause of death is heat.

The man's identity is trickier, but is solved six weeks later after a woman in California watches an Univision report on border deaths and calls to report a missing person: her brother, Manuel Vargas Saldivar. Investigators confirm the match when, using a special infrared camera, they spot an "M" tattoo on his forearm that the sister told them about.

Saldivar, the father of four and a gardener, was returning to Sacramento, Calif., after his first visit home to see his father in 19 years.

DNA IS LAST SHOT

Anderson is in the property room, looking for the belongings found with Case No. 10-1157, a skeleton discovered on June 11 in a wash near Rio Rico. He pulls a Mexican voter card out of the bag and holds it up in the air.

He looks at the name but covers the date of birth with his finger.

"I like to work blind," he says.

The Mexican Consulate believes the remains are from the man on this ID card: 40-year-old Alberto Donato Lopez. They have asked Anderson to cut a bone sample for DNA analysis.

Before he does, Anderson wants evidence the remains are those of an adult male, and not a woman or a much younger or older man.

The Mexican government pays for DNA tests used to confirm tentative matches. U.S. state and federal grants pay for DNA samples from unidentified bodies in an effort to match to them with people in the national missing-persons database. The tests cost $800-$3,000 each.

This case is a prime candidate for DNA analysis. There is no face for family to identify, no skin that might have a defining tattoo or birthmark, no fingers to print.

The DNA sample will be sent to a lab in Virginia, and compared to samples from the family. This is the best science has to offer, but it accounts for a small portion of solved cases - 98 of 1,030 from 2001 to 2009. Most are solved the old-fashioned way: through matching descriptions, fingerprints and visual confirmation from families looking at photos.

NOT MUCH IDENTIFYING DETAIL: Forensic anthropologist Dr. Bruce Anderson gets involved in nearly every case in which identity is unknown - more than half of them. Illegal border crossers often don't carry ID and many are found as skeletal remains, as in Case No. 10-1157. The last option for cases like this is often cutting bone samples to send for DNA analysis.

"A lot of Bones"

Anderson unzips another body bag, revealing a skeleton covered in beetles and other small bugs.

There is no head.

Animals could have chewed it off, along with his hands, Anderson surmises.

He focuses on the pelvis, which lets anthropologists determine the person's sex 99 percent of the time because in women it's adapted for childbirth.

After using a scalpel to pry away excess skin and tissue, he cuts out the left and right pelvic bones with a small electric saw.

He puts the bones in a pan with water, then adds both collarbones and the tip of the fourth rib. These will help him estimate age.

He sprinkles sodium carbonate, a softening agent, over the water and moves the pot onto a burner for about an hour, then lets the bones soak overnight to get off cartilage.

Anderson has worked on about 100 of the 160 unidentified border crossers - UBCs, according to office lingo - that have come in each year for the last decade.

Hislaid-back appearance - he's in scrubs and Crocs whether in the exam room or his office - belies the intensity he applies to his work, which focuses almost exclusively on illegal border crossers.

"Probably over the half of the UBCs that have come in here, I've had my hands on their bodies or bones," he says. "That's a lot of bodies. A lot of bones."

DAY 3: Hope, then letdown

Dr. Eric Peters stares into the mouth of a woman Tohono O'odham police dropped off earlier this morning.

"Pretty distinctive dental work," he says. "Hardly any decomposition.

"Pretty young," he adds.

It's about 10:15 a.m. and Peters has already done three exams: two suicides and a natural death.

The deputy chief medical examiner, Peters has worked here since 1998. Autopsies of illegal border crossers have gone from an occasional part of his work to a daily occurrence in summer.

These exams are almost flip-flopped from the rest. The focus in other exams is cause of death because identity is usually known. Most Americans die with multiple forms of ID.

But with border crossers, the point is to find clues that could lead to identification.

Peters estimates this woman, Case No. 10-1239, died recently, perhaps within the last day. There is only a little decomposition on her legs and back. Her face is still recognizable.

Border Patrol agents found her about 11 miles southwest of the village of Cowlic on the Tohono O'odham Nation.

"She should be pretty easy to ID with those teeth," Peters says. They're capped in gold and silver.

TWO PHONE NUMBERS, NO HELP: Hidden inside the watch pocket of a woman's blue jeans, investigators find a tiny piece of plastic tied with a bow. On it are two partially smeared phone numbers. One belongs to a smuggler who won't talk, the other to someone who claims no one he knows would be crossing the border illegally.

Then, pathologist assistant Krystal Poulin makes what could be a key discovery: Inside the watch pocket of the woman's jeans is a tiny piece of plastic tied with a bow. It's no bigger than a ladybug. Peters tries to untie it, and finally cuts it open.

Inside is a torn piece of paper with two partially smeared phone numbers.

"Why would someone wrap up a phone number so tight?" he asks.

This is investigator Chuck Harding's case and he comes to see what they've found. He writes down the numbers for Ton of the Mexican Consulate to call. One is from Guatemala and the other from Caborca, Sonora, Mexico.

Harding is optimistic because the woman was traveling with three other people, who survived. "Maybe we'll get lucky," he says.

Peters echoes that: "Hopefully we'll have her ID by the end of the day."

But their optimism soon wanes. The man who answered the Guatemalan phone number said he knew nothing about any relative who planned to cross the border. The Caborca number was a smuggler who wouldn't talk. And the three people found with the woman told Ton they didn't know her.

It's possible the man in Guatemala and the three travelers were scared and might provide more information down the road. But for now, the woman's identification is unknown.

Bones tell a story

Anderson, the forensic anthropologist, scrubs the bones he left soaking the night before.

"Looks like he's going to be past 25," Anderson says. "The shapes of the bones are diagnostically adult male."

More than three-fourth of the illegal border crossers this office handles are men, and the average age is 28 to 29. Ninety-two percent of the identified are Mexican.

Anderson estimates the man's age at 35, plus or minus nine. The ID card says 40.

Next, Anderson uses an anthropometer to measure the hip socket and femur to get a height estimate. He measures the femoral head, or hip socket: 41 millimeters. Next he measures the femur: 404 millimeters.

"So he is going to be quite short," Anderson says.

He punches numbers into the calculator on his computer. The formula tells him the man was between 4-feet, 11-inches and 5-foot-4.

Anderson's anthro exam matches the family's description of Donato Lopez, so he sends off the bone sample for DNA analysis.

AN ID CARD, BUT A LOT OF DOUBTS: Pathologist assistants Krystal Poulin, left, and Marcie Yates look at an identification card found under the sole of a boot recovered from the desert. Investigators hoped it would help them ID Case No. 10-1227, but aren't sure the two are related. Heat-induced hallucinations often lead people to do things like take off their clothes before they die.

Prints and "logic problems"

Poulin, the pathologist assistant, had hoped to take fingerprints of the woman's severed hands a full 24 hours ago. But autopsies ran past quitting time. So today's the day.

She wipes the hands with acetone and uses a paint roller to ink the fingers.

"These are pretty good, actually," she says.

Holding the palm in her left hand, she presses each finger against a thin strip of paper at the edge of the counter, rolling it back and forth.

She does each finger again on another strip of paper and then both thumbs on the third. Applying more ink as necessary, she completes more than a dozen sheets, each with "Case No. 10-1194, Jane Doe" at the top.

"If she has anything on file, we should be able to get a hit," Poulin says.

Poulin used to work in labs, drawing blood, but she got hooked on "Dr. G, Medical Examiner" on Discovery Health and decided she wanted this job.

"I like logic problems," she says.

Dealing with the dead can be less stressful, too.

"These ones are silent," she says. "They don't complain."

DAY 4: Recovery at dawn

The full moon slips below the horizon as Field Agent Hairston drives a Medical Examiner van west from his home in Tucson.

It's at about 4 a.m. and he's headed toward Sasabe to pick up a woman who died the night before.

He got his first call at around 11 p.m. But Pima County sheriff's deputies decided they wanted more time to investigate. Hairston went back to bed.

When his phone rang again at 3 a.m., Investigator Hernandez told him to go. After two years on the job, he's used to middle-of-the night interruptions.

When he's on call, he keeps his uniform at the ready and a notepad and pen on the entertainment center in his living room. Even half awake, he makes sure to write clearly the who, what and where.

Veteran investigators like Hernandez wait several seconds before they talk, giving agents time to wake up.

When Hairston arrives at 4:50 a.m., he finds a Pima County sheriff's vehicle parked 7.5 miles north of the border near the entrance to the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. A tattered white body bag is taped to what looks like a metal luggage rack mounted to the bumper of the deputy's SUV.

"How's it going?" Hairston asks the deputy.

"Just terrific." He's been waiting for two hours and isn't feeling chatty.

"Anything abnormal about this one?" Hairston asks.

"It's a homicide investigation," the deputy says.

Hairston begins to open the body bag for the cursory inspection agents perform in the field but stops. He decides it's best to wait until he knows why deputies suspect this is a homicide.

The Border Patrol found her east of here the night before. Agents performed CPR but she died at the scene.

It's a quick handoff, and Hairston is back en route to Tucson as the sun peeks out from behind the mountains. After another sleepless night on call, he'll work straight through until the end of the day.

Hairston stays awake without the assistance of coffee. He doesn't like hot drinks.

"Sometimes at night I don't know how I do it," he says. "Sunflower seeds? I eat a lot of sunflower seeds out there."

The self-proclaimed "Army brat," born and raised in Germany, has always been interested in serial killers, which is why he took the job here two years ago after he earned a bachelor's degree in criminal justice. Before he pursued a career in law enforcement, he wanted to make sure he could handle being around dead bodies.

At 7 a.m., Investigator Hernandez arrives at the office on his bike. He rides 11 miles each way from home as part of an exercise routine that also includes afternoon swims and lunch-hour jogs. He has lost more than 110 pounds in two years.

Hernandez has been up most of the night, too, fielding calls as the on-duty investigator. This case is particularly challenging because of the talk of it being a homicide.

The dead woman's green t-shirt has been cut open by officials who administered CPR. Several white pads used to monitor her heart are stuck to her chest and stomach.

Hairston puts a red-orange tag around her left ankle with her case number: 10-1248. He zips up the bag and writes on it her presumed name, found on an ID card and confirmed by others found with her: "Filiberta Vasquez."

Hernandez returns with wet hair and fresh clothes.

"What a night," he says.

A question of homicide

A few hours later Dr. Gregory Hess is ready to begin his examination of the woman believed to be Vasquez, 42, of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The former Air Force flight surgeon, who joined the office three years ago, dials Hernandez's desk to get more information, and puts him on speaker phone.

Hernandez has spoken with the Border Patrol and relays what he learned:

POSSIBLE HOMICIDE: Assistant Medical Examiner Dr. Gregory Hess examines an illegal border crosser, Case No. 10-1248. The Border Patrol found this woman alive east of Sasabe the night before but was unable to save her. Hess is examining her for signs of a trauma because he was told she fell 15 feet before dying.

"Apparently, she was traveling in a group of about 11 people," Hernandez says. "They broke off into a smaller group, her and three other people, when she started to become distressed and apparently fell approximately 15 feet.

"These three folks that stopped to help her, dragged her off of the trail she was on and gave her some type of rubbing alcohol or something to drink," Hernandez says. "I don't know how much of that is lost in translation but that's what he said to me.

"Then, these three folks who stopped to render some type of assistance went to look for somebody to kind of get some help for her. They ran into an agent for the Border Patrol and that's when they called Borstar (the Border Patrol's search, rescue and trauma team). But when Borstar landed she was down hill quick and was pronounced dead.

"Then because of this rubbing-alcohol incident, they said, 'That sounds kind of fishy,' they ended up calling it a homicide."

But after interviewing everyone officers decided there was nothing suspicious.

Investigators are confident they know who she is, so Dr. Hess will focus on cause of death in his exam. He'll look for signs of trauma that would be caused by a fall. And he'll have toxicology tests run to see if she ingested rubbing alcohol, although he doubts it.

"My suspicion is that it's just plain not true," Hess says, "and that they might have had some kind of bug juice like Gatorade that they may have concocted and tried to give that to her as rehydrant but that may have translated into rubbing alcohol somehow."

Hess and Poulin, the pathologist assistant, look over her belongings, which include four photos. Three are of women who could be her sisters or mother. A fourth is of a little girl.

Marcie Yates, another pathologist assistant, goes through Vasquez's matted hair and takes out a hair tie. She rolls her next to a sink and begins cleaning her body with a hose attached to the ceiling.

A clean face makes a better picture to show possible relatives. But there's a more humane reason for the washing, Yates says: "We always try to get them clean."

Hess doesn't find any skull fracture or broken bones, just scrapes on her head, arms and legs. If she fell, it didn't kill her. He believes she most likely died from the heat but he's going to list the cause of death as pending until he gets toxicology results.

The tests later reveal he was right: She didn't ingest any rubbing alcohol. After his third autopsy of the morning, Hess fits in a quick workout and then picks up more exams in the afternoon.

One of them is a 31-year-old man Tucsonan who died when his pickup caught fire the previous night on I-10 near Marana.

A FAILED RESCUE: Field Agent Trevis Hairston, right, unzips the body bag of 23-year-old Rey David Perez Vera, Case No. 10-1264, as Field Agent Tessa Lee looks on. Someone traveling with him called 911, and Border Patrol agents tried to save him but he died. He carried a birth certificate and a prayer card to San Antonio, patron saint of lost things and missing people.

DAY 5: Corridor of death

No introductions are needed as Tohono O'odham police Detective Sean Dailey greets Field Agent Hairston behind the Sells hospital just before 10 a.m.

Hairston and other field agents know all of the tribal police officers. Most of the bodies they pick up are discovered along the 75 miles of international border the Tohono O'odham Nation shares with Mexico.

Hairston's here to pick up Case No. 10-1264, found the day before three miles southeast of Sells in the deadliest migrant trail in the country - an 18-mile-wide swath of mesquite and cactus running from Mexico north through Sells.

Bordered by the Baboquivari Mountains on the east and by open desert on the west, this smuggling corridor has long been popular because it's remote, sparsely populated and near foothills and canyons that offer cover. Those characteristics makes it ideal for avoiding detection, but also mean people who get lost or left behind face long odds for survival.

They walk in the hospital's back entrance, which leads to a morgue with room for two bodies.

"This is a UDA from last night," Dailey says, using law enforcement lingo for "undocumented alien."

Somebody in the man's travel group called 911 for help, triggering an all-day search by Borstar. By the time he was found, he was clinging to life.

He was pronounced dead at just before 6 p.m. On him agents found a birth certificate for Rey David Perez Vera, 23, of Hidalgo, Mexico.

"It came in real late and we were just really busy," says Dailey, explaining why they left him in the morgue overnight rather than calling the Medical Examiner.

Dailey says Tohono O'odham police and the Border Patrol were slammed the day before working several rescues. Dailey spent eight hours on a quad in the western part of the Nation looking for a father who is still missing this morning and feared to be dead.

Earlier that day, two badly dehydrated men came out to a road about 25 miles north of the border, and asked for help. They said they had left their father behind but they couldn't give good directions.

"I don't think they even knew where they were," Dailey says.

The veteran detective doesn't care why people cross. His job is to get answers for relatives.

"I'll bust my butt to get closure for these families," Dailey says.

Lately, people have been found in more remote areas, he says. Twice this year, officers have flown to scenes in helicopters because they were unreachable by car.

Each case takes about eight hours because officers treat each body recovery as a possible homicide. They process the crime scene, bring in the body and produce a report.

Dailey is on call all weekend and praying for a quiet day. "I'm fried," he says.

Hairston takes the body and leaves, both knowing they could see each other within hours, especially if the father is found. By noon, Hairston is back in Tucson, unloading the body at the Medical Examiner's Office.

"What do we got?" asks Kniffin, the pathologist assistant.

"A UBC," Hairston says.

"Has he been there a long time?" Kniffin asks.

"No, he's fresh."

As Hairston unzips the bag, that "freshness" is haunting. The young man's eyes are still open, his clothes only dusty and his neck still red from a sunburn. He looks like he could sit up and walk away.

On him, Hairston finds a laminated prayer card of San Antonio. This is the patron saint of lost things and missing people, but some believe he can help them find their way on long journeys.

DAY 6: Questions, 1 answer

Monday morning feels like Friday afternoon for Investigator Harding.

He worked all weekend, at the office during the day and taking 18 calls from home between 4 p.m. and 7:30 a.m. over three nights. Then he started his regular work week.

"I'm exhausted," he says.

Staffing is lean, so on-call duty is followed by regular shifts. Harding will work through Thursday, including being on call Wednesday night, before getting a long weekend.

But he's enjoying forensic science, an early passion fueled by his love of the 1970s TV show "Quincy, M.E.," starring Jack Klugman as a coroner. He started as a pre-med student at the UA with plans to become a pathologist. But he changed his mind, earned a business degree and worked 20 years as a chef before finally getting a job at the Medical Examiner's Office.

After three years as a pathologist assistant, he became an investigator six months ago. He's still learning to juggle his case load, now at 18. Eleven are John and Jane Does, probably UBCs.

Nobody complains about the border-crosser cases. But the truth is, especially in the summer, they push everyone to the brink.

Robin Reineke, doctoral student at the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, left, who helps the Medical Examiner match unidentified border crossers, searches through unidentified border crosser documents with the Consul General of Guatemala Julia Guzmán, right, while going over cases of missing Guatemalans at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner on June 28, 2010.

"Beyond Grief. It's Terror."

A bookcase is filled with thick red and black binders labeled "Unknowns." There's one for each year since 1994.

On another shelf are five more large binders labeled, "UBC missing persons." There's one for men for each year since 2005-06 and one for women that covers 2001 to 2010.

Reineke, the UA grad student, spends her time comparing the two, looking for a possible match. This morning she checks her voice mail to find it full with new missing-persons reports.

"I'm concerned because this is a really high volume," Reineke says. "It makes me nervous for what we are going to be looking at for the summer."

Her words, spoken in late June, prove prophetic when the office handles the bodies of 59 illegal border crossers in July, the second-worst month on record.

This is Reineke's fourth summer in the office. She is paid from an anonymous $200,000 donation that is being used to create a database of unidentified and missing persons, and develop a computer program that can find matches between the two. In the meantime, Reineke does the work by hand.

Each day she comes in, usually three times a week, she fills out missing-person forms based on her phone messages. She also gets reports from the Tucson-based Coalición de Derechos Humanos and the local Mexican Consulate and from family members, such as the sister in California who called about Case No. 10-1227.

For each missing person, she lists all unidentified border crossers brought to the office since the date he or she was last seen. She looks for anything that could signal a match: clothing, dental work, something on the ID card.

She works backwards, eliminating cases that definitely don't match, leaving ones that might. She's made about 20 matches but she can't keep up.

There are more than 500 unidentified border crossers still in the database and 771 missing-people reports. When she started in 2006, there were 222 unidentified border crossers and about 200 missing-persons reports.

The work, she says, is "like trying to count stones as an avalanche is coming down the hill."

Today she's working on the case of a 32-year-old Guatemalan man missing since June 6. The report came from a family member in North Carolina who was talking to Reineke on one phone and the wife in Guatemala on another.

The couple has a 11-month-old baby and decided their best bet to support the family was for the husband to go to the United States. His wife last talked to him before he left Altar, Sonora, a popular staging town about 55 miles south of the border.

She received an anonymous call later from someone, perhaps a people smuggler, saying her husband had walked for three hours and given up.

The anguish of the unknown has the wife so upset that she can't produce breast milk for the baby, she tells Reineke. And she can't afford formula.

"It gives us an idea of the emotional and economic impact it has on people," Reineke says.

Not knowing can be the worst for families. With death, there is a reckoning. When somebody is lost, the distress never ends.

"It's beyond grief," Reineke says. "It's terror."

Reineke finds 10 unidentified male border crossers who arrived at the office since or just before the man was last seen. Two have been tentatively identified and five more don't match, leaving three possibilities.

She's about to open the case files again when the receptionist tells her the Guatemalan consul is here from Phoenix to discuss several missing-persons cases.

Consul Julia Guzmán hands her a Guatemalan ID card for an 18-year-old man they think might be a body found last summer. The card gives the office a fingerprint to compare to those taken from the man's hands.

Reineke has already tentatively identified him as William Vasquez Barrera after his family told her he had a root canal, porcelain front teeth and missing molars. She found a man who arrived the month Barrera went missing with the same teeth, and the rest matched up, too: age, height and clothing.

The only thing separating this case from a positive ID is a fingerprint analysis.

"I'll have to find out from the investigator where the prints are and we'll do a comparison," she says, "but hopefully that will work out."

There's lots more to talk about, including two sons looking for their father, Juan Manuel Esteban Sebastian. It's the same case Detective Dailey told Agent Hairston about on the reservation the day before.

Guzmán's cell phone rings. A Guatemalan man living in Nebraska has driven to Arizona in search of his wife, who he fears is dead. Guzmán takes a piece of paper and begins asking questions.

"What is the deceased's name?" she asks in Spanish.

"How old?"

"And this is the real name?"

"When did she die?"

The signal drops; the call is lost.

While they wait for the caller to ring back, Reineke starts a new missing-person report.

Guzmán's phone rings again. She learns the missing woman went back to Guatemala in 2008 to wait for legal residency but was denied. She was trying to cross illegally to rejoin her husband.

Reineke wants to know if the family has dental information, but the caller hangs up before Guzmán can ask. Both unidentified women who have come in since June 5 have distinctive dental work.

The caller's wife was last seen wearing blue jeans, a black shirt and a green sweater. Reineke looks through the list of belongings found with the two women she mentioned.

"No," she says. "No green sweater."

THE BODY COOLER: Investigator Tessa Lee puts the body of Case No. 10-1227, John Doe, into one of two body coolers, which are both nearly full even though together they have space for 220 bodies. More bodies are being held in a refrigerated trailer that is only used when deaths soar, as they have this year.

NOTHING AS SIMPLE AS IT SEEMS

It's noon and Investigator Thompson has a new case: Tohono O'odham police have found another body west of Sells.

The field agents know every inch of this road. Whether going to the reservation or toward Three Points and south, most body recoveries happen out here. Back in July 2005 when the office handled a record 69 bodies, agents passed each other day after day.

Today Hairston is meeting a police officer to transfer the body from her truck to his van.

Early this decade, field agents spent much more time going into the desert and bagging bodies. But as deaths soared, Tohono O'odham police and Pima County sheriff's deputies realized it was quicker to meet field agents rather than wait for them at the scene.

This afternoon a Tohono O'odham ranger waits for Hairston outside the tribal-police station, the bagged body in the bed of her pickup truck. It's 108 degrees when he arrives at about 1:45 p.m.

"He was in the fetal position," the ranger says. "Just looks like he was dragging himself in the dirt."

Hairston unzips the bag.

"Boy, he's young," he says.

The man's face is charred black on the side that was likely exposed to the sun. He's wearing a peach t-shirt with gray stripes, gray dress pants and brown dress shoes with no shoelaces.

At the office, Hairston finds a cell phone and a wallet in his pockets. The wallet has a Mexican voter registration card for Hindemas Mejia-Peres of Benito Juarez, Quintana Roo, the southeast Mexican state bordering Belize.

Hairston holds up the ID to the man's face. They seem to match.

Next, he empties the backpack found with the man. Everything is organized: a roll of toilet paper, a toothbrush, a small tube of toothpaste, scissors, two packages of electrolyte powder, a small tube of lotion, a tube of Ultra Bengay, a clove of garlic, underwear and a white collared shirt.

"This is the best-dressed UBC I've ever seen," Hairston says.

"It's like he's going to the office," says Field Agent Lee.

Also found with him are a black-leather-bound Bible, an evangelical hymn book and three pieces of paper with dozens of tiny, neat phone numbers. Inside a small matchbook in his pocket are two short needles and, deep at the bottom, a tightly rolled dollar bill.

The agents believe this is the person on the Mexican ID card. So Hairston puts the belongings in a biohazard bag, places it inside the body bag and zips up the young man and the things he carried so carefully on his final journey.

Case No. 10-1277 closed, it seems. Hairston takes a black marker and writes on the bag: "Mejia-Peres, Hindemas."

But things are rarely so simple.

LOVED ONES LEFT BEHIND: These photos were found in the backpack of Case No. 10-1277, an illegal border crosser found dead on the Tohono O'odham Nation. The man, determined to be a 28-year-old Guatemalan, also carried a leather-bound bible, an Evangelical hymn book, a clove of garlic and a white, collared shirt.

In the weeks to come, photos of the man and his belongings land in the e-mail of Guzmán, the Guatemalan Consul. She recalls a missing-person report filed by a Miami man whose description of his cousin matches the pictures. She calls him, and he calls an uncle in Guatemala to ask if he knows the name on the missing man's fake Mexican ID card.

He does. Hindemas Mejia-Peres.

It seems the well-dressed, highly organized young man was prepared for everything - even his death. By giving his uncle the name on the fake ID, he helps connect the dots of his identity and ensures himself a proper funeral.

Six weeks after arriving here, 28-year-old Enemias Francisco Lopez Lopez flies home in a casket.

Another death, another twist. And for today, at least, a mystery solved.

Contact reporter Brady McCombs at 573-4213 or bmccombs@azstarnet.com.