As thousands of women crossed the border with their children this summer, the government opened more detention centers to send the message that they will be sent back if they come illegally.

But the difference between being detained or dropped off at a bus station to reunite with family members in the United States could be a matter of the day they crossed, a chicken pox quarantine — or just plain luck.

Reyna Perdomo left her native El Salvador on June 26. She was caught in South Texas on July 5, a few days after the government opened a family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico, that can hold nearly 700 women and their children.

Perdomo said she met another woman on her journey. Both of them were brought to Tucson to be processed. But while Perdomo was taken to Artesia, the other woman was sent on her way.

“I cried, because she was only held three days, and she was told to call her family so they could buy her bus ticket to Minnesota,” Perdomo said recently from the Border Patrol training facility in southeastern New Mexico. Perdomo also has family in Minnesota.

She’s been detained for more than two months, with limited access to an attorney who can prepare her asylum claim. Several groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union, say that’s all too common, and on Friday they sued the federal government for creating what they called an illegal “deportation mill,” where women seeking protection from violence in their home countries are not being given their fair day in court.

“You can’t win an asylum case if you don’t have the time to put it together,” said Laura Lichter, former president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association and one of the attorneys who has spent time in Artesia. “It’s an extremely complicated area of law.”

About two-thirds of the women in Artesia would have successful asylum claims, Lichter said, if they were represented by an attorney and had time to prepare their cases.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials said in an email that the agency makes the determination on a case-by-case basis, depending on the availability of beds in family detention centers when migrants are apprehended.

The women are also screened for criminal history, said Amber Cargile, ICE spokeswoman in Phoenix. Those who have been in trouble or deported before, for instance, are more likely to be detained.

Other factors are at play, too. In late July, for example, ICE stopped receiving and deporting women and children from the Artesia facility for about 10 days after a chicken pox quarantine.

To Laura Lunn, an immigration attorney who volunteered at the Artesia center and worked with Perdomo, whether a family is detained or released depends on luck.

“If bed space is full when someone is being processed, then they get to be released — likely on bond or on their own recognizance,” she said.

The reasons are often unclear. Lunn saw one case where two sisters came to the country to live with their mother in Florida. One was sent on her way, while the other remains in Artesia.

government response

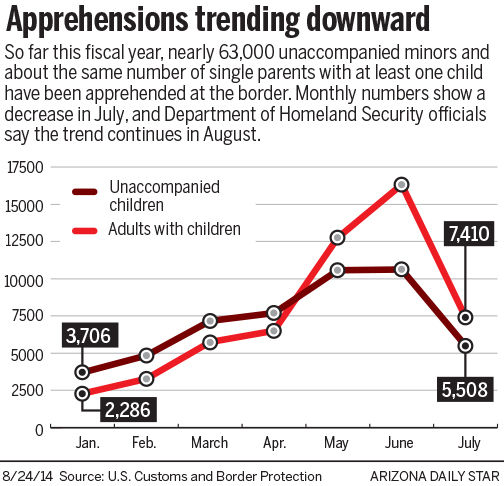

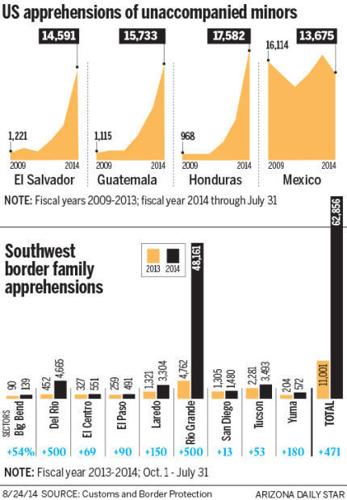

So far this fiscal year, which ends on Sept. 30, nearly 63,000 single parents with at least one child have been apprehended at the border — a nearly 500 percent increase over last year.

In response to the surge, the government is opening more centers to hold families. Until this year, there was only one — an 85-bed facility in Pennsylvania.

The government also started working to deport unaccompanied minors and families more quickly. Nearly 300 women have been deported with their children from the two family detention centers in Texas and New Mexico, the Los Angeles Times reported.

“We continue to have much work to do to address this issue, and our message continues to be clear — our border is not open to illegal migration,” Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson has said. “Unless you qualify for some form of humanitarian relief, we will send you back consistent with our laws and values.”

The government should have responded earlier to the increase, said Mark Krikorian, executive director for the Center for Immigration Studies, a nonprofit organization that advocates immigration reduction in the United States. There should be a variety of places that can be adapted quickly when necessary, he said.

But immigration attorneys and human-rights advocates say detention is not the solution.

“We would love to see the immigration court system get enough resources and judges and lawyers to speed up its processes,” said Clara Long, a Human Rights Watch researcher who visited the Artesia center in July.

In Krikorian’s view, not detaining people is what led to the current problem.

“Letting people go with permisos, summons to show to immigration court, and having people calling home and saying ‘It’s true’ is one of the major reasons we have this spike in illegal crossings in South Texas,” he said.

Krikorian thinks everyone who crosses the border illegally should be detained, and all the adults should be prosecuted for illegal entry.

one shot

Nearly all of the women in the Artesia detention center are in expedited removal, meaning they don’t have a right to see an immigration judge unless they say they are afraid to return to their home country and they pass an asylum officer’s interview. About two-thirds of those detained in Artesia have asked to go through the asylum process, attorneys said.

Perdomo had her first appearance before an immigration judge via videoconference this week and will have another one in September. She is seeking asylum, and passed the first credible-fear interview. She’s among the 38 percent of women in Artesia who have cleared that threshold.

She said she had a small business in El Salvador selling tacos, bread and sodas. One day she was robbed and told that from that day on, she had to pay the criminals a fee to operate.

“I’m alone,” said the 23-year-old single mother. “I don’t have anyone to help me survive, and if I didn’t work for them, they would kill me and my son.”

She reached out to her sisters in Minnesota, who helped her flee. El Salvador is one of the world’s most dangerous countries, with an annual rate of 41 homicides per 100,000 people. She couldn’t go to the police, she said, because many of them are corrupt.

Despite that, asylum approval rates from Central America have generally been low. U.S. immigration courts granted 6 percent to 7 percent of asylum applications from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras in fiscal year 2012.

While detention of asylum seekers in expedited removal proceedings is mandatory, it becomes discretionary when the person passes the credible-fear interview. Perdomo, like many of the women in Artesia, is applying to be released on bond. But ICE has decided the Artesia women are not eligible because they pose a risk to national security: Releasing them would send a message to others that if they come, they can stay.

So for Perdomo and her fellow detainees, their only shot at leaving the center is to go before an immigration judge. Until recently, the few bonds that had been set were for $25,000 and $30,000.

A different judge started issuing bonds that are more aligned with the national averages for people in immigration proceedings. That’s closer to $6,000, Lunn said. Perdomo has her next court appearance on Sept. 8.

rock, hard place

Asylum cases before immigration judges can take months, or even years.

“For low-priority detainees, it makes no sense to continue to be detained,” Long said, “especially when children are involved.”

Perdomo, like many of her fellow detainees, is growing desperate.

Some days she wonders what life is worth if she’s locked up, she said in a telephone interview. It’s especially bad when her 2-year-old boy, Jesson Chacon, cries and she has no control over what can be done to help him. In detention, access to doctors and medicine is up to strangers, not mothers.

Half the children were under 6½ years old, and many were toddlers or still nursing at the end of July, when Long, with Human Rights Watch, visited.

“Until I actually spent the week in Artesia, I didn’t really get in a gut level why detaining families is so absolutely wrong,” immigration lawyer Lichter said.

“These are not summer camps, despite pictures of Barbie dolls on the bed. People are under extreme stress,” she said. “Mothers are watching their children getting sick and wither in front of them.”

Leticia Zamarripa, an ICE spokeswoman in El Paso, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. But in a Department of Homeland Security release, Johnson said, “ICE ensures that family detention facilities operate in an open environment, which includes classrooms with state-certified teachers, access to an online legal library and bilingual teachers.”

Sometimes Perdomo said it feels like a dead end.

“If I’m in my country, it’s a terrible suffering because I fear for my life and the life of my son,” she said. “But I come here only to fall into another type of suffering.”