A group of business owners and concerned citizens has been trying to convince local leaders that the homeless problem in Tucson is a serious threat to their livelihoods and public safety, and that immediate action to find solutions is needed.

The Tucson Crime Free Coalition advocates for “adequate staffing and resources for law enforcement, treatment for those in need, and prosecution for criminals who are unwilling to abide by our laws,” per the group’s mission statement.

Dozens of members attended the Pima County Board of Supervisors’ Nov. 15 meeting to speak to the crime they say is perpetuated by homeless people residing near their businesses. Speakers said they’re losing business due to hesitant customers, and they are doling out money for repairs after frequent property damage.

Grant Krueger, the owner of three restaurants in St. Phillips Plaza, said small businesses are “dying on the vine here in Tucson,” detailing how homeless people are bathing in the fountains in the plaza on River Road and Campbell Avenue, using drugs in the bathrooms and “scaring off my customers and making it unsafe for my business.”

Steve Juhan, president of the Grant Road Industrial Center Owner’s Association that represents about 20 property owners, said he’s dealt with vandalism of two air-conditioning units that cost him $25,000 in damage, while other businesses in the center have had to pay for other repairs to their buildings because of vandalism they say is being caused by a growing homeless population.

The coalition has caught the attention of local politicians, has a weekly meeting with County Administrator Jan Lesher, and after the Nov. 15 meeting, influenced the board of supervisors’ action to address increasing homelessness.

The county board unanimously approved directing county administration to plan for the expansion of the county’s pretrial services operations to the county-owned Mission Annex near the Pima County jail.

Pretrial services, a division of the Pima County Superior Court, assesses the release eligibility for those booked into the county jail to help judges make decisions on defendants’ release conditions. The board is set to discuss what an expansion of pretrial services would look like, and how it would address some of the crime-related issues brought on by homelessness, at its Tuesday, Dec. 6, meeting.

County leadership has also been working with the city to come up with ways to address homelessness for months — but the expansion of pretrial services is the first substantive, though uncertain, response.

“We’ve been meeting for two, three months, and nothing has happened,” Lesher said. “And there are some things happening … but I talk with people and they don’t feel they can safely bring their children to their own businesses, or they’re losing inventory because of criminal activity of their business. Nothing would happen quickly enough if I was in their shoes.”

Estevan Park

In a wash nestled between the edge of Estevan Park near downtown Tucson and the Union Pacific railroad tracks, dozens of homeless people have set up camps in tents and makeshift shelters stretching throughout the sunken stretch of land.

Across the park’s large recreational field sits the Dig Deep Athletic Training Academy, a nonprofit that trains student athletes. Covaughn DeBoskie began renting out the city-owned building in 2020, but said parents have become reluctant to bring their children to train at the academy due to increased criminal activity at the adjacent park.

DeBoskie said he’s had to sleep at the gym at times to prevent vandalism, which has included attempted break-ins with crowbars and graffiti on the building. “Our numbers have dwindled because of this,” which has “hurt us for having to pay this lease,” he said.

But also adjacent to Estevan Park is the Splinter Collective, a community center that provides aid to the surrounding unsheltered population and has recently begun a partnership with Tucson. The center has a charging station and a free store with fresh produce and bread for the unsheltered community.

Natalie Brewster Nguyen co-owns the center and has developed an understanding of what she calls a “constellation of issues” that cause the homeless people at Estevan Park to reside there.

Two people organize their belongings at Estevan Park.

“They are experiencing high levels of instability, trauma and violence,” she said, which results in mental health issues, substance-abuse disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Brewster Nguyen said she’s seen several attempts by the city to remove the park encampment.

“People got really scared, and kind of scattered to the winds, and people were traumatized and devastated,” she said. “When you see that happen, you also watch people who had been struggling to manage their substance-use disorder, have been struggling to manage their mental health, you watch them totally destabilize.”

In August, Brewster Nguyen said, Mayor Regina Romero, Vice Mayor Lane Santa Cruz — whose Ward 1 contains Estevan Park — and other city staff met with the Splinter Collective at the park to negotiate conditions at the encampment. While the partnership is in its nascent stages, the Splinter Collective has identified park managers to clean up litter, maintain the park’s restrooms and ensure playground equipment is clean, according to the city. A report from Assistant City Manager Tim Thomure said, “Parks and Recreation staff will be working with the Splinter Collective to ensure a successful partnership.”

As far as the Tucson Crime Free Coalition’s work with the city goes, Josh Jacobsen, a restaurant owner and steering leader of the coalition, said the group has met with Romero and some council members, but “they are not seeing the same immediate urgency that we are to find a solution for this problem.”

The group has caught the attention of the Goldwater Institute, a conservative think-tank that’s supporting a lawsuit that Phoenix property owners filed against the city of Phoenix for a stretch of a downtown area encampment dubbed “the Zone.” The group says the encampment has become a public nuisance that spurs frequent break-ins at nearby businesses.

The Goldwater Institute wrote a letter to Tucson’s council members on Nov. 29 to “express concerns regarding the homelessness crisis in Tucson.” While the letter lauds the county’s board for passing its Nov. 15 motion, Municipal Affairs Liaison Austin VanDerHeyden wrote, “The county cannot adequately resolve the underlying problem without the city’s involvement, and Tucson citizens and county officials have told us that the city refuses to engage.”

Jacobsen said the Goldwater Institute intends to continue working with the coalition, and “hopes that the city comes along so that, frankly, we don’t have to file a lawsuit against the city.”

Josh Jacobsen, of Tucson Crime Free Coalition, stands at a homeless encampment that has grown at Estevan Park.

Tucson’s approach to homelessness

The city’s made its approach to homelessness clear: it relies on a housing-first model that focuses on providing people shelter without barriers. People are not required to participate in behavioral health services or substance abuse treatment as a condition to receive shelter, but the programs are there for those willing to accept.

The city has four shelter sites managed by its housing-first staff and Community Bridges, a social services organization. According to the city, 152 people currently live at the sites that have sheltered 414 residents this year through Nov. 21. About 225 of those occupants have moved into permanent housing.

Also, the city and county have agreed to fund a multi-agency resource coordinator, Amaris Vasquez, to coordinate homeless protocol between the two jurisdictions. Tucson has also assembled a homelessness task force that meets weekly with city department heads and county administrators.

There’s a variety of reasons the homelessness crisis has reached the level Tucson is seeing, Vasquez said. The pervasiveness of substance abuse — compounded by the fentanyl crisis — pandemic-induced evictions and a lack of available government aid to meet the demand, all play a role. The focus when working with businesses, however, is centered on the criminal activity the city finds when working with unsheltered communities.

“We’re not talking about the unsheltered that, you know, don’t have a home and need help getting one. We’re talking about the people who are choosing to break the law and we have a way to hold them accountable,” Vasquez said.

Vasquez is set to speak to the City Council at its Dec. 6 meeting about “community safety and strategic initiatives for unsheltered,” a conversation the council requested updates on every 60 days.

The City Council will discuss an encampment clean-up program the city launched at the end of October, largely in response to concerns from local businesses. The program allows people to report homeless encampments that results in a joint response from city and social service workers. Based on the danger the encampments pose to the public, encampment inhabitants are either allowed to stay after a cleanup or forced to leave with 72 hours’ notice.

As of Nov. 22, the city has cleared out 52 encampments by relocating or “identifying shelter/housing for occupants,” cleaned up 146 sites that “do not pose health or safety risks,” and cleaned 55 sites with no current occupants, according to Thomure’s report.

While clean-up crews and social services were provided at the sites, the report says, 15% to 18% of cases required Tucson Police Department intervention over “concerns regarding illegal activity.”

Jacobsen said the coalition doesn’t believe the city’s encampment response is a valid solution “because really all it does is move people around. So we don’t think that it’s an effective tool for getting to the root of the issue, being the lawlessness and the crime and the drug use.”

Expanding pretrial services

Instead, Jacobsen’s looking forward to the pretrial services expansion county supervisors approved, a solution he said will provide a place to take homeless people who are arrested “where there are wraparound services … and then people ultimately would have the decision to make: door A leads to treatment, door B leads to the actual Pima County jail.”

Supervisor Steve Christy has also expressed support for the dual path of treatment or incarceration, but Lesher said current considerations for a triage and probation facility are still being discussed.

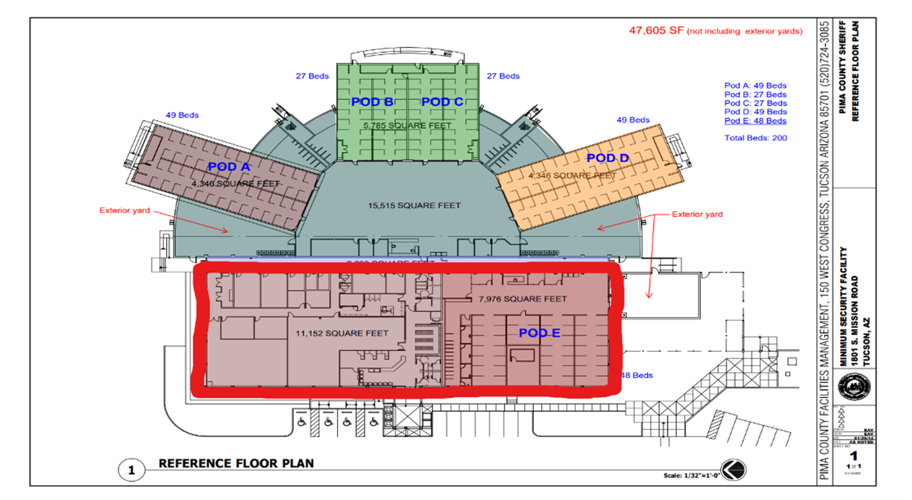

The Mission Annex at 1801 S. Mission Road, which previously served as a minimum security facility for the sheriff’s department, has been left vacant with a broken air conditioning system and electrical problems. It’s not yet clear, Lesher said, what the expansion of pretrial services and its operations would look like.

A homeless encampment has grown at Estevan Park, 1001 N Main Ave.

Initial considerations are to use an 11,152-square-foot area of the building where pretrial staff can establish release conditions for those charged with nonviolent misdemeanors that are “tied to the engagement of resources for behavioral health services, substance abuse services, housing services, and/or employment services,” a memo from Lesher said. Another part of the area could become a detox unit for those struggling with substance use disorders.

Staff estimates completing the Mission Annex renovations could take until late January, but a “first-phase launch” in collaboration with social service providers could happen in February if other stakeholders agree to the changes.

The motion the board approved Nov. 15 also stated, “anyone who violates laws in place to protect public health and safety should be arrested and prosecuted. Anything that prevents the enforcement of our laws should be identified and removed,” and told county administration to work with other criminal justice agencies to do so.

Current considerations for the expansion of pretrial services are to create a processing center and detox facility in a 11,152 square-foot area of a county-owned building at 1801 S. Mission Road.

The board directed county administrators to report on current county and city of Tucson efforts to provide social services that address the root causes of homelessness while identifying opportunities to expand services. Officials will also look into using the county’s remaining federal COVID-19 relief dollars to carry out some of the plans. Lesher’s memo said staff has determined American Rescue Plan funds can be used for the pretrial expansion but reallocating the dollars will be an ongoing task at a yet-to-be-determined cost.

However, pretrial services is a division of the Superior Court, so judges, and sometimes, pretrial services staff, make the ultimate call on who is released from jail.

Pretrial services can release those charged with nonviolent misdemeanors before they see a judge in a process called “prebooking release.” In 2019, this process was conducted in trailers outside the jail where about 75% of individuals arrested were released without a jail booking, according to Lesher’s memo.

The memo details potential revisions to the pretrial process discussed at a Nov. 28 meeting where representatives from county administration, pretrial services, the superior court, TPD, the county attorney’s office and the public defender’s office, which included ways to keep better track of repeat offenders. Staff could place harsher restrictions on those frequently arrested at the same locations, the memo said.

Attendees also discussed improving wraparound services in the pretrial process, as many arrests can be traced back to drug abuse and actions taken to obtain those substances. “For example, participation in substance use treatment could be required as a ‘condition of release’ and arranged immediately,” Lesher wrote.

While the considerations could contradict the city’s housing-first model that provides shelter without conditions, and places Tucson’s policy against criminalizing homelessness into murky waters, they would only be applied to those found breaking the law.

“Being homeless is not a crime. However, if you’re choosing to engage in behavior that is criminal, then that’s a different story,” Vasquez said. “My goal is to find common ground (between the county and the city), it’s not to pick a side.”

Lesher agrees that crime is part of the overall problem, but said the county plans a wide approach to deal with all issues brought on by homelessness.

“There’s a different population, frankly, those are individuals who are homeless in a temporary way, and we can help find them shelter. But that chronic individual, or the person who is caught participating in criminal activity, is who we’re really focused on now,” Lesher said. “I know we’ve been at this several months, but if we could fix homelessness in a couple of months, you know, we’d take our show on the road.”