Millions of Americans made the trek to the narrow strip of land across the United States where the moon completely blocked the light of the sun during Monday’s total solar eclipse.

Among those who soaked in the brief darkness of totality were students from Cienega High School’s astronomy club who took part in a citizen scientist experiment to capture images of the sun’s elusive corona.

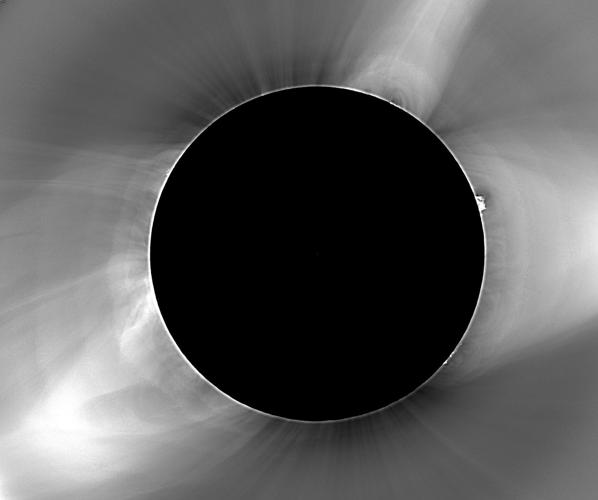

The corona is the sun’s incredibly hot plasma atmosphere that generates the solar wind. The corona is usually hidden by the blinding light of our star, making it difficult for astronomers to untangle its mysteries.

The best time to view the corona is during a total solar eclipse. In a single location, though, the most time that the corona can be seen is during the frustratingly short 2 minutes and 20 seconds of totality, which isn’t enough for a deep understanding of the corona and solar winds that it produces.

To tackle this problem, Matt Penn, National Solar Observatory astronomer, coordinated a nationwide citizen scientist experiment, called the Citizen CATE — Continental-America Telescopic Eclipse — Experiment.

Citizen scientists from 27 universities, 22 high schools and 19 other groups participated in a transcontinental network, including students from Cienega who traveled to Pawnee City, Nebraska.

On the day of the eclipse, 68 telescopes captured images of the corona along the 2,500-mile-long path of totality. Solar astronomers will stitch together the images into a 90-minute movie to study the speeds of the inner corona.

The eclipse was the only opportunity for this kind of detailed science because the part of the corona nearest the sun’s surface is too hard to see with current sun-blocking methods.

When studying the sun, astronomers use occulting disks in telescopes to drown out the light from the sun, but this only works so well. The moon however, is the best occulting disk.

Understanding the corona, which generates solar wind, will allow scientists to confirm their theories about how it works and refine their models of the sun and solar wind based on this information.

The solar wind is ejected from the sun and interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field, which has consequences for our electrical grid. Typically, power companies can accommodate incoming current from the sun. But particularly large solar storms can overload the electrical grid and cause widespread power outages. If power companies can predict these events, then they can mitigate the damage that they might cause.

“Think about hurricanes. If you had 20 minutes of warning for hurricanes, you’re not going to be able to evacuate very many people, but if you have a week or a day, you can do a lot more,” Penn said.

“Fantastic” response

So far, 56 project sites successfully collected data from Monday’s eclipse. One had instrumentation problems, 5 were blocked by clouds and the results from seven sites are still unknown. Penn only expected to have data from about 30 sites, so he’s over the moon about the outcome.

“The best published work is from three sites, so I thought, if we can do a factor of 10 better, with 30, that’d be fantastic,” Penn said.

Penn estimates it will be about two months before the final movie is stitched together. So far, he has a 10-minute clip up on the citizencate.org website. In the clip, thin, faint, white tendrils of the corona worm their way out from the sun.

Any published research results from this data will include the Cienega High students’ names as well as any other citizen scientists who contributed.

“Miracle” for Students

Cienega students met with Penn for more than a year to perfect the process so that things went smoothly on eclipse day. The plan was to set up a telescope, calibrate it and then when totality hit to simply allow the telescope to record for about two minutes as the corona shone.

They trained especially hard this summer, practicing camera alignment, calibration, taking the lens off and other techniques to get the best images possible.

“We practiced once every two weeks at the start of the summer. The last month, we did it once or twice a week every day,” said student Bruno Acevedo.

Unfortunately, weather was the only thing out of their control. On game day, they were disappointed to see clouds hanging in the sky.

Despite the gray skies, “We got everything set up as much as we could right as the eclipse started,” said student Brynn Brettell.

It started to rain.

“We started to huddle around the telescope,” she said. But their patience paid off and the “clouds broke through. It was a miracle.”

Jack Erickson, the teacher leading the Cienega astronomy club who accompanied them to Pawnee, said that it took them a third of the time as usual to set up the telescope.

Once all the excitement and anxiety over the rain passed and they activated the telescopes, they sat back and enjoyed the total eclipse.

The corona was a “white heavenly glow of light,” said student Bentley Bee. “It brought awe to me.”

“Seeing the eclipse was the coolest thing I’ve ever done,” said Brettell. “It makes me think I want to do astronomy in the future.”

So what’s next for the club? The students hope to be ambassadors to the OSIRIS-REx mission and maybe travel to the upcoming solar eclipses in South America.