Talk about mixed messages.

Forecasts of continued hotter weather, greater risk of “megadroughts,” more destructive wildfires, more tree dieoffs, future Colorado River shortages and more deaths from extreme heat peppered a University of Arizona climate change workshop last week.

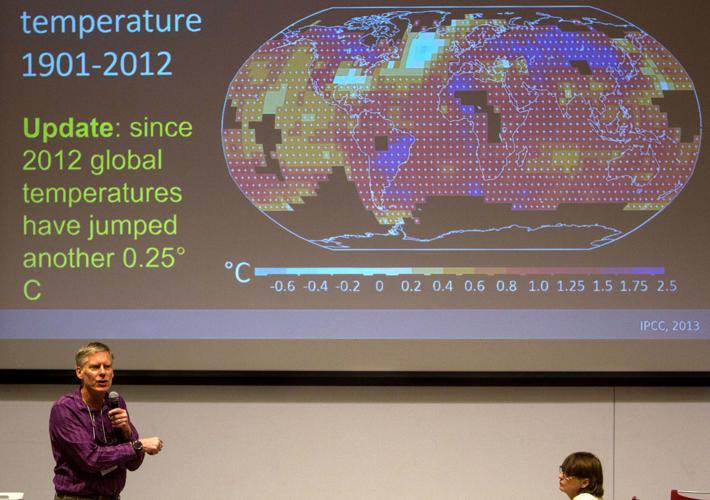

While the groundbreaking Paris Climate Accord has pledged to limit future temperature increases to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), “I don’t think you need to worry about 1.5 or 2 degrees” as the upward temperature limit, said a semi-joking Diana Liverman, a UA geography professor and a workshop co-organizer. “They are not on the horizon.”

But at the same time, many speakers talked of plans and hopes for how Tucsonans can adapt to the specter of scorching days and parched landscapes. Researchers talked of using solar panels to shade and grow garden vegetables and studying how to turn downtown into a low-water, low-energy-use mecca, and urging residents to tailor their future landscaping plans to match their yards’ “microclimates.”

Former UA researcher Jonathan Overpeck says the biggest uncertainty about climate change is “what humans are going to do” about fossil fuels that create greenhouse gases.

The two-day workshop drew about 80 people. Featuring 40 speakers from the UA and out of state, it was sponsored by the University of Arizona Institute of the Environment, the University of Michigan and the federal National Center for Atmospheric Research. Financing came from the National Science Foundation.

Commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions made in the December 2016 Paris accord and in other discussions were weak enough as to “take us significantly above 2 degrees C warming, globally, and probably even higher in the Southwest,” Liverman told the gathering Thursday.

She’s working with other researchers on a report on the feasibility of holding temperature increases to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels. It’s being done for the International Panel on Climate Change, which monitors global climate health.

The report’s conclusions remain under wraps, but several major newspapers have published stories on leaked versions that say meeting this goal is impossible. That conclusion is supported by “a lot of papers I’ve read,” was all Liverman would say about the report.

To even hope to reach that goal, the world must achieve “negative emissions” of greenhouse gases, in which civilization takes more out of the atmosphere than it puts in, she said.

University of Arizona geography professor Diana Liverman helped assemble an international gathering of migration experts and climate scientists at a two-day workshop on campus.

To do that requires extensive reforestation in “deforested” areas, she said. It would require creating new forests, better farmland management and storing carbon underground so it doesn’t escape into the atmosphere, she said.

“All of these are feasible, but they’re occurring at a very, very slow level,” Liverman said.

But at the same time, just-published research out of the UA warns that wildfire size and damages to forests will only increase as the West’s climate keeps warming and drying. The amount of area burned should increase by up to five times by 2040 in half of the Western states, including Arizona, said workshop speaker and study co-author Donald Falk, a professor at the UA’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“The bottom line is that the gigantic fire seasons we had in California this year, Montana and Idaho in 2017, are likely to become the norm by the mid-20th century,” Falk said in an interview.

As for megadroughts, up to four of at least 35 years have struck the Southwest in the past 1,000 years, said speaker Toby Ault, a Cornell University earth and atmospheric sciences professor. A megadrought would be worse than the Dust Bowl drought of the 1930s, the West’s major drought of the 1950s and the 18-year drought currently plaguing the Colorado River Basin, he said.

Past megadroughts are suspected of playing a primary role in the collapse of past civilizations, including the Anasazi on the Colorado Plateau, Cambodia’s Khmer empire, the Mayan empire, China’s Yuan dynasty and Bolivia’s Tiwanaku, capital of a dominant pre-Inca civilization between 500 and 900 AD, said Ault, who got a doctorate at UA.

In the period 2030-2060, a temperature increases of 1 to 2 degrees pose a 20 to 50 percent risk of another megadrought, Ault said later. If precipitation drops or temperatures increase faster, “those risks would be considerably higher,” Ault said.

After hearing several discussions about climate computer models and climate science, former UA researcher Jonathan Overpeck told the workshop that the biggest future uncertainty about climate isn’t in the science or computer models.

“It’s what humans are going to do” about fossil fuel use that creates the greenhouse gases that climate scientists say causes warmer temperatures, said Overpeck, now dean of the University of Michigan’s School of Environment and Sustainability.

But even under severe drought and heat, Tucsonans could still maintain landscapes, said Margaret Livingston, a professor at UA landscape architecture. They’ll simply have to change.

Some of that change will come from continuing the area’s longstanding conversion from non-native to native plants that use less water. But people will also have to match their yards’ landscaping to its “microclimates,” she said.

That would mean planting some kinds of desert plants on their home’s east side where it’s generally cooler than on the west side, she said. Perhaps solar panels could shade west-side plants.

Switching from non-native to native trees will make planting street trees more difficult because natives have many trunks, spanning beyond sidewalks, she said. But with planting of smaller shrubs in streetscapes, solar panels there could work like nurse trees in the desert, shading yuccas.

Solar panels have also shaded crops of kale, tomatoes, chiltepines and cabbage, among other garden veggies planted for the past year and a half at the Biosphere II research laboratory near Oracle and at Manzo Elementary School and Rincon-University High School in midtown Tucson. For the most part, that experiment using the panels as shade structures has worked, said Greg Baron-Gifford, an associate professor at the UA’s School of Geography and Development.

At the Biosphere 2 site near Oracle, researchers from UA and elsewhere are testing the use of solar panels as shade structures to extend the growing season for crops such as tomatoes and chiltepeno peppers along with others.

Tomato crops under the panels were 40 percent bigger and their growing season expanded significantly compared to those grown in open air, he said. Chiltepine crops were about one-third larger. Jalapeno crops under the panels were no better than normal, but used one-third less water, he said.

On the flip side, thanks to the plants’ shade, solar panels were 9 degrees Celsius cooler than normal, and much more efficient, he said.

UA architecture assistant professor Courtney Crosson’s students have over two years produced two booklength reports outlining how downtown could be made much more energy efficient by using taller, more tightly packed buildings by 2050.

They’ve looked at using more autonomous, self-driving cars to allow the city to reduce parking spaces, leaving more room for trees along streets, and maybe even closing of some streets to encourage walking, she said.

Rainwater gathering “pods” could provide potable water to the homeless and average persons in summer heat waves, she said.

Asked if these schemes are realistic, Crosson said that’s the goal, and that several city and county government staffers have come to the classes to pose questions and comments to the students.

“That said, the goal to reach carbon and water neutrality is ambitious,” said Crosson. She’s also separately doing research on the feasibility of using rainwater harvesting on a large scale in Tucson in case Central Arizona Project water goes away.

But another speaker, UA Sustainability Director Ben Champion, said as the need for air cooling grows, buildings will become more energy intensive and their air-conditioning will be less efficient.

“Arizona wouldn’t be what it is population-wise without the invention of air conditioning,” he said. “If our survival depends on a continuing growth model or sustaining population that we have, we have to deal with the energy intensive issue.”

Summing up, UA’s Liverman said it probably wasn’t just megadroughts that caused the past collapses of civilizations. It could have been conflicts, diseases and overuse of the soil.

She said she’s hopeful about the potential for climate adaptation here and the tremendous creativity that people can marshal.

“The question is not whether this civilization will survive; it’s who will do well or who will suffer.

“People ask me should I move to Tucson. I tell them if you have enough money, you can buy water and air conditioning.

“It’s people without money we have to worry about.”