The image of a stopped clock — right twice a day — could apply nicely to either of two Republican politicians on opposing sides of the U.S.-Russia relationship.

But which prominent American represents the stopped clock?

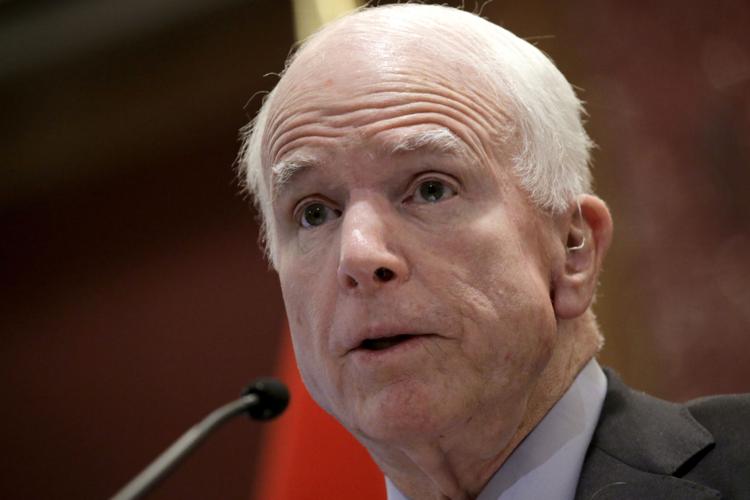

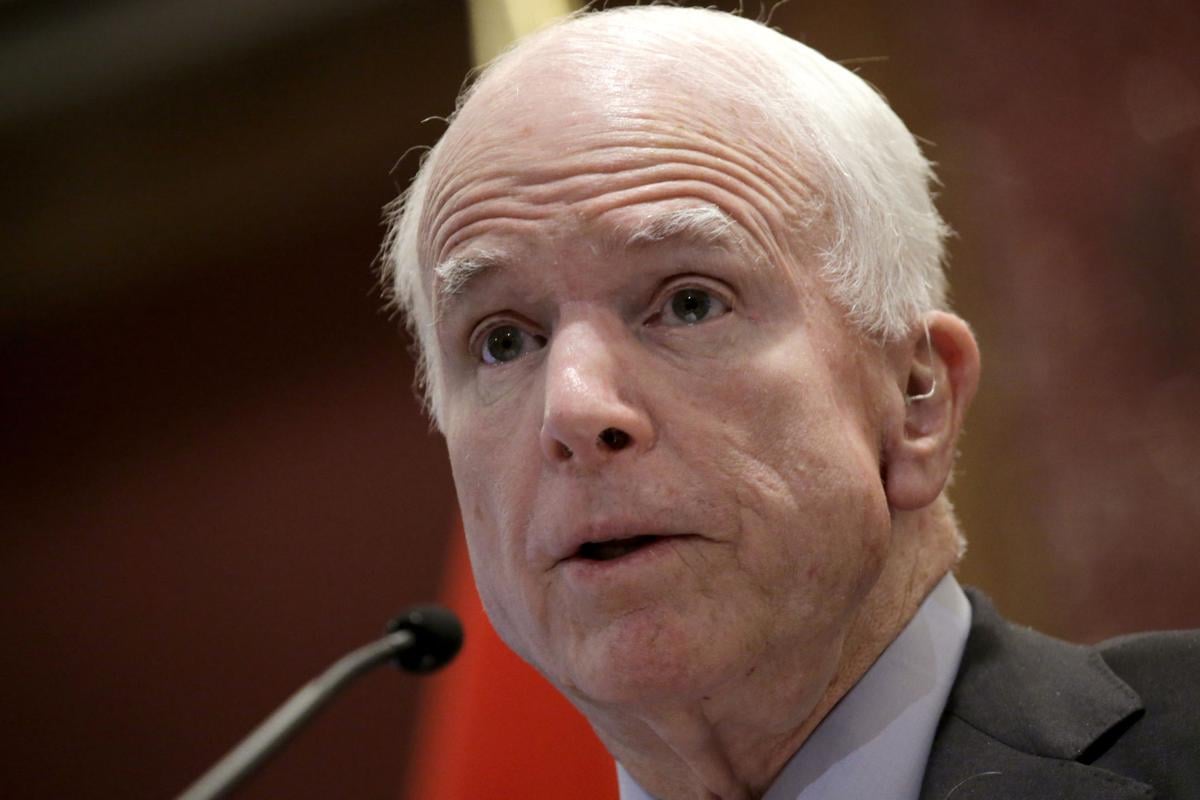

My pick was Sen. John McCain, who showed up in the Baltic countries on Ukraine’s front line with Russia over New Year’s weekend. McCain always seems game for U.S. intervention abroad, right or wrong, and in this case he seems to me smart to offer reassurances to countries that want our protection from Russia and are worried about our new president.

But then I spoke with John “Pat” Willerton, a professor and Russia specialist in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Arizona. Willerton made use of the stopped-clock image, too — this time in reference to Donald Trump. Willerton supported Hillary Clinton for president, but much preferred Trump’s conciliatory approach toward Vladimir Putin.

“He’s right on Russia,” Willerton said of Trump on Tuesday.

McCain, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., visited Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine and Georgia in an unannounced trip that began Dec. 26 and lasted a week. It was similar to trips McCain has made through the years in which he has acted as a sort of shadow secretary of state, presenting an alternative American policy to the one put forth by the sitting president.

Perhaps surprisingly, it looks like McCain will continue this practice with a Republican in the White House, as he did with the Democrat who beat him, Barack Obama.

But maybe it shouldn’t be surprising. One of the most disturbing aspects of Trump’s run for president was his consistent embrace of Putin, a dictator who suppresses dissent at home and acts increasingly aggressive abroad.

Infamously, when asked about Putin’s alleged killing of journalists and opponents in December 2015, Trump said, “He’s running his country, and at least he’s a leader unlike what we have in this country.”

This comment showed a willingness to turn a blind eye to Putin’s bad acts, which raised the ire of old-fashioned hardliners like McCain. It infuriated me, too.

So I was happy to see the tweets start rolling in from McCain last week from the nervous Baltics and from Russian border zones that have been the site of military conflicts — Ukraine and South Ossetia in Georgia. The biggest surprise was a tweet from near Mariupol, a Ukrainian city on the front line of the battle with Russian-backed separatist groups.

“Spending #NewYears- Eve w/ brave #Ukrainian Marines at a forward combat outpost — we stand w/ them in their fight against #Putin’s aggression,” McCain wrote, using the hashtags common on Twitter.

Putin is pushing forward in a multifaceted offensive that has undermined western democracies. Leaving aside the discussion of hacking during the presidential campaign, Russia engaged in campaign disinformation, helping spread false stories and create doubt about the political system we live in.

McCain has scheduled a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing Thursday on foreign cyberthreats.

Disinformation is not new, but the way Russia has been using the internet to do it is, as Daniel Rothenberg, co-director of the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University explained to me Tuesday.

“Information warfare is nothing new,” he said. “There are things that are new about the movement of information.”

Rothenberg cited the hacking of the U.S. Government’s Office of Personnel Management files, probably by China, which released volumes of information on federal employees previously unimaginable to our adversaries.

In the case of last year’s election campaign, what became clear was adversaries’ “ability to forge people’s debates and play off of people’s uncertainties.”

Willerton, the UA professor, sees things differently.

“I have a totally different view of Russia than most of the people you’ll talk to,” he said.

In an interview and in two papers he’s written for an Italian journal, Willerton explained that Russia views the U.S. as encroaching on its sphere of influence. Russians, he said, generally view Putin as a great leader restoring their country’s glory.

He dismissed McCain’s trip as “a stunt.” And in a paper published in November after the election, Willerton said Trump ought to be given a chance to try to make peace with Putin’s Russia, especially over Ukraine.

“Top congressional Republicans such as Senator John McCain have long led the charge in Putin-bashing,” he wrote. “Are these politicians capable of permitting Trump to engage in a new rapprochement with Putin?”

Of course, the new administration will formulate its own foreign policy, and it appears Trump will try a friendlier approach with Putin. The strange thing about his positioning, though, is that he talks about Putin and Russia as if they were a greater power than they are.

Russia has a weak economy and is only prominent on the world stage thanks to its aggression on the ground and in the world of disinformation.

So it is good that there are congressional Republicans like McCain willing to press our case, the case of the western liberal democracies, assertively. It at least balances Trump’s apparent willingness to negotiate with Russia from a position of weakness. And it makes clear that we have values that won’t be easily sacrificed in the new administration.