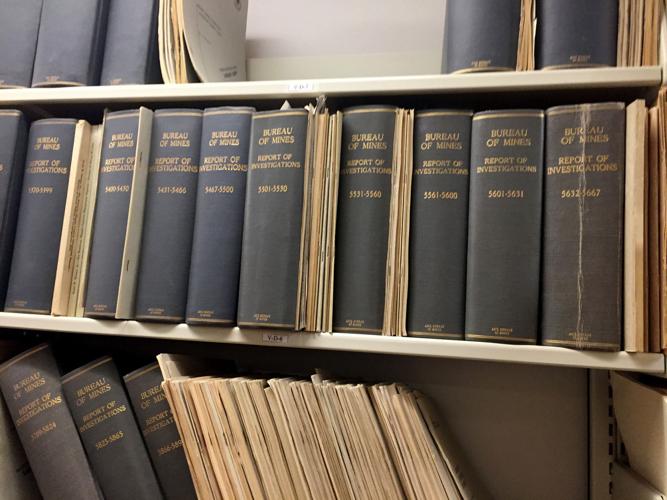

A University of Arizona librarian was in the stacks Tuesday afternoon packing up old U.S. Bureau of Mines circulars and reports of investigation.

A representative of a sportsman group was trying to figure out how to move thousands of topographical maps of Arizona, all housed in large metal cases with rolling drawers.

And the staff at the Arizona Geological Survey was preparing for an important meeting Wednesday. Today, they finally break apart the decades-old collections of their library, parceling out the pieces among members of Southern Arizona’s geological and mining communities.

It’s a frantic, haphazard effort to remove a treasured resource, necessitated by an edict from Phoenix. In the state budget, passed last month, the Legislature ordered that the Geological Survey be absorbed by the University of Arizona. The state’s previous $941,000 appropriation for the survey was zeroed out.

Of course, this was done via the state’s top-down budget process, in which the affected agencies and departments are given no opportunity to explain their activities. The message from those who pushed the measure was: You figure out how to do it and how to pay for it. You’ll get no help from us.

This was done in the name of consolidation of government agencies and cost savings, but also on the argument that it will help end users.

“Anytime we can find a way to make government work better for people who interact with it, we want to approach that opportunity,” Daniel Scarpinato, the spokesman for Gov. Doug Ducey, told me Tuesday. “In this particular case, you have a lot of resources and wisdom to bear at the U of A that can really enhance the geological survey’s work.

“On top of that, you have an agency that’s more of a research/academic type agency than a state agency like DCS (Department of Child Safety) that’s providing some kind of regulatory role.”

It’s true the geological survey is different from typical state agencies, in that it performs research projects and provides information. And when your philosophy of governing is that less is more, then naturally you’ll look askance at oddball offices like this.

But I don’t see why it or similar offices, such as the Employment and Population Statistics division of the Arizona Department of Administration, should be downgraded. They provide valuable, baseline information to industry and the public.

“If there’s one state in this country that ought to have a geological survey, it’s Arizona,” Bob Cummings, president of Saguaro GeoServices, said Tuesday. “Pennsylvania can have a well-funded geological survey, but we can’t?”

He and other end users I talked to couldn’t disagree more that this consolidation is a good idea. Since the University of Arizona had no significant input into the decision, it had to scramble to find space. It found 2,500 square feet to house the 10,000-square-foot survey office.

Naturally, the library and other archival material is what’s being sloughed off to whoever could offer a good home, as state geologist Lee Allison explained.

“The state library has been down. The state archive has been down. We shipped off three boxes to the American Geosciences Institute this morning,” he said. “The Arizona Railroad Museum in Chandler was down and picked up a lot of topographic maps.”

Private companies, too, have carted off some of the archives for their own purposes.

The survey is retaining 100 boxes, and the rest is scheduled to go out today.

That hurts a lot of geologists and small or new mining companies, as my friend Brad Herbert explained.

“For me, when I go into a new project, the first thing I do is go into the Geological Survey library,” Herbert, a geologist, said. “I look up any information on the site I'm looking at — the existing geology, water depths.”

The survey has been working to digitize the geology of the entire state — or at least as much as has been researched already. But that’s a long, incomplete process, one that will be harder to complete thanks to this state move.

For the little guys, the loss of the library means the disappearance of a valuable source of baseline data for people involved in road-building, mining and other projects around Arizona. It also gives a further advantage to the big companies and erodes the public sphere of knowledge, Cummings said.

The big companies can afford to do the basic research on the geology of a given area that little companies can’t. And when they do it, they keep it, he said.

“You don’t want to make everything proprietary,” he said.

But that’s the effect of casually diminishing the agencies like the Arizona Geological Survey. The public sphere of knowledge, the one that anyone can access, shrinks. The private sphere grows and becomes available only to insiders or those who can pay the price.