PHOENIX — People who store child pornography in the “cloud” cannot claim an illegal search when the operator of the remote storage site turns them in to authorities.

That’s the conclusion of the Arizona Court of Appeals in rejecting a bid by a Tucson man to toss his criminal conviction and his 170-year prison sentence.

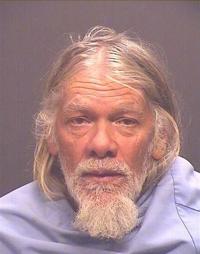

The case dates to 2016 when Google discovered 19 images of child pornography at the Google+ Photos account of Edgar Fristoe. It forwarded the findings to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

That information eventually found its was to a Tucson police detective who used the info, including Fristoe’s phone number, email address and IP address, to obtain a search warrant for his home and cell phone. That led to several images on the phone.

A trial judge rejected Fristoe’s bid to suppress the evidence as anything gathered was based on a warrantless search. That led to a three-day bench trial, a finding of guilt and 10 terms of 17 years each, to be serve consecutively.

On appeal, Fristoe does not dispute the Fourth Amendment is a ban on warrantless searches by the government and that Google is a private company.

But he argued that the court should consider Google to be a “government agent” based on what he said is the government’s knowledge “of and acquiescence in Google’s intrusion into user’s private files.” And he said Google acted with the intent of assisting law enforcement.

Appellate Judge Karl Eppich, writing for the unanimous court, said those arguments hold no water.

He pointed out that Fristoe never alleged that law enforcement asked Google to search his particular account, or even knew that Google was going to do that.

Eppich acknowledged that federal law does require third parties, such as Google, to report child pornography it finds to the missing children’s center. But nothing in that law requires such a search.

The judge also said Fristoe never proved that Google’s search was motivated to assist law enforcement rather than simply “protect its private business interests.” That was backed up by a declaration from a Google employee that the company has “a strong business interest” in ensuring its products are “free of illegal content” that it monitors its platform both to protect its public image and to retain and attract customers.

“Here, Google, acting of its own accord, was the first to search Fristoe’s Google+ Photos and discover the pornographic images in question,” Eppich wrote. “Because these invasions of Fristoe’s claimed expectation of privacy were committed by a private party and not through state action, they did not violate the Fourth Amendment.”