Before the pandemic, about 1,800 first-year students placed into Math 100 at the University of Arizona, the most baseline math class the university offers. This past year, almost 2,800 students, around a third of the incoming class, placed into the course, which focuses on addition, division and basic algebraic equations.

For staff and faculty within the math department, the stark increase in enrollment of their entry-level class has been shocking.

“The need caused us to hit our breaking point,” said Michelle Woodward, the director of online instruction of math at UA who helps oversee the course.

The UA is not alone. Colleges across the country are struggling with academic setbacks faced by students who were in high school during the pandemic. According to education nonprofit The Hechinger Report, math programs have especially struggled to help students catch up.

“A big component of what we have our conversations about is not just the math, but how do we re-engage a population that’s not had practice in a classroom,” Woodward said. “We believe that they are capable of doing this math, and we believe that they can be successful.”

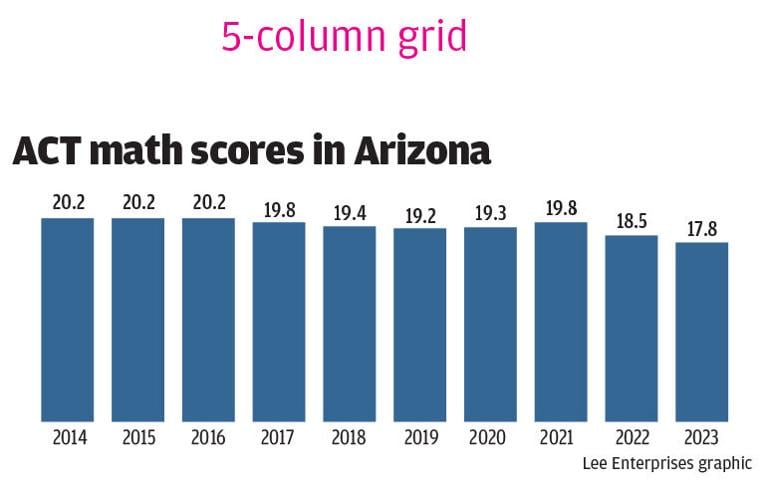

According to new data from ACT, a nonprofit with a nationally recognized standardized test that centers on college readiness, only 29% of Arizona high schoolers met the national benchmark score for math in 2023, which was a 22.

Since 2014, the ACT math scores have trended downwards in Arizona, and the pandemic has only accelerated the slope.

In 2019, the average math score for high schoolers in Arizona who took the ACT was a 19.2. By 2023, it had dropped to a 17.8.

Oftentimes, it is up to college professors to help their students catch up.

“We’ve realized it isn’t a one size fits all solution,” Woodward said. “We had to really adjust to make sure that we were trying to meet those individual needs of students.”

Woodward believes the pandemic exacerbated the differences in college preparedness among students.

“Some of them are amazing and had tremendous support and are doing really, really well,” she said. “Others are really struggling. And those that are, I think it’s a bit systemic.”

In an effort to curb that disparity, staff at the UA teach online summer programs to help incoming first-year students hit the ground running in their math courses.

Wildcat Leap, which started in 2020, is available to all incoming first-year students the summer before they start classes. It’s a three-week boot camp, offered for free, that helps students learn the skills they need to succeed in college math courses.

“We work on things like growth mindset and dealing with math anxiety in addition to the actual math,” Woodward said. “Part of the class time is about learning strategies.”

Not every math class has a Wildcat Leap summer program, however.

Tina Deemer, the director of academic and support services in the UA math department, said the gaps in learning are prevalent even in higher level courses.

“I’m working with calculus two right now, and when you have students who’ve already completed calculus one, you sort of assume they know certain things,” she said. “Still, there are definitely some gaps happening there.”

Despite the national and statewide drop in math scores, James Gray, the head of math at Pima Community College, remains optimistic about the abilities of his students.

“It’s a very natural, normal thing that when you’re learning something, you’re going to make missteps and you’re going to use the wrong language and make mistakes,” Gray said. “It’s up to us to ask ourselves how do we support students? And how do we support learning?”

Gray is working with the faculty and staff at PCC to redesign some of the core classes taught, though he said that isn’t in direct response to an increase in help needed.

“I think there’s a lot of evidence that suggests that students still have the capacity to learn, despite experience in the pandemic,” he said. “We have lots of evidence that suggests that students are just fine.”

The COVID-19 pandemic spared no state or region as it caused historic learning setbacks for America’s children, erasing decades of academic progress and widening racial disparities, according to results of a national test that provide the sharpest look yet at the scale of the crisis. Across the country, math scores saw their largest decreases ever. Reading scores dropped to 1992 levels. Nearly four in 10 eighth graders failed to grasp basic math concepts. Not a single state saw a notable improvement in their average test scores, with some simply treading water at best.