The Army Corps of Engineers gives complete backing to Hudbay Minerals Inc.’s position that Rosemont Mine opponents incorrectly criticized the company’s plans to compensate for Rosemont’s damage to washes.

Hudbay’s long-discussed, oft-changed plans to overhaul and preserve sections of Sonoita Creek that it owns in Santa Cruz County will adequately compensate for Rosemont’s damage to washes on its site, the Corps said in approving the final permit needed for the $1.9 billion mine project’s construction. The federal agency joined Hudbay, the mine owner, in rebutting all arguments against this plan made by the EPA, Pima County and conservation groups.

The damage will be done by the discharge of fill material that will bury about 37 acres of washes in the Santa Rita Mountains. Hudbay said it would compensate for that damage by re-establishing, enhancing, rehabilitating and preserving stretches of Sonoita Creek and its tributaries, floodplain and landscape buffers.

An approved mitigation plan is legally required for the mine’s Clean Water Act permit. This is the first of five Rosemont mitigation plans proposed since 2011 that the Corps has approved.

But the plan isn’t out of the woods because environmentalists have attacked it in their U.S. District Court lawsuit, filed March 27, that seeks to overturn the Corps’ permit.

The Corps’ 49-page environmental analysis of the Rosemont plan, published with its permit decision, comes after the county, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Save the Scenic Santa Ritas and other mine opponents and critics carried on what amounts to a running, written debate with Hudbay over the plan, records obtained by the Arizona Daily Star through the Freedom of Information Act show.

“The resources to be preserved contribute significantly to the ecological sustainability of the watershed. Sonoita Creek Ranch, with its associated certificated water rights, occupies a key location within the watershed and the creek and floodplain restoration would provide for substantial wildlife habitat and corridor opportunities as well as substantial stream function improvement,” the Corps said about the plan in its permit decision.

But EPA’s 27 pages of comments attacking the plan, the lack of formal, public review of it and the lack of long-term financial commitments from Hudbay to carry out the mitigation plan are cited in the lawsuit by Save the Scenic Santa Ritas and other opponents.

What’s needed now is a more thorough environmental analysis of the proposed measures, with the public, tribes and other expert agencies able to weigh in, as the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act require, said Randy Serraglio, a conservation advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the groups that sued.

“The EPA has said repeatedly that there is no proof that this plan will provide any benefits at all. In any event, most of the mitigation is outside the watershed and will do nothing to alleviate the severe, permanent depletion of groundwater that supports Empire Gulch, Cienega Creek, Davidson Canyon and Tucson’s water supply,” Serraglio said.

Here are the plan’s details, and some of the concerns and responses.

The plan

It centers on the Sonoita Creek and Rail X ranches, totaling 1,580 acres and adjoining Arizona 82, between Sonoita and Patagonia. The site is about 12½ miles south of the mine site.

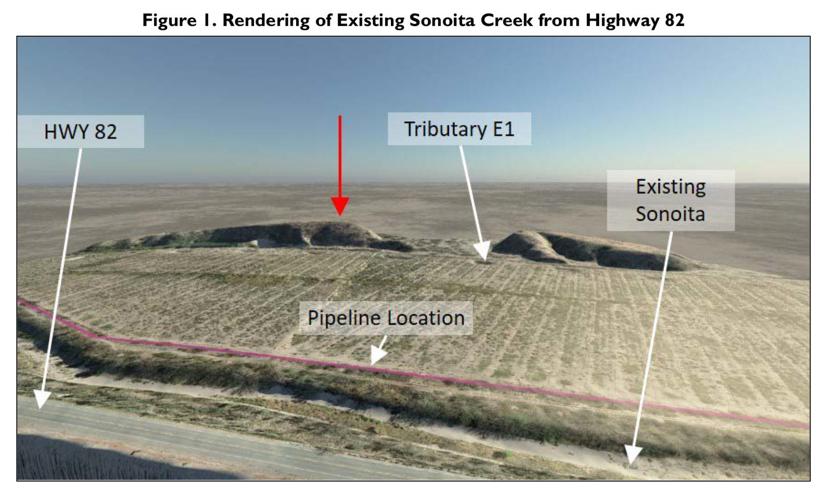

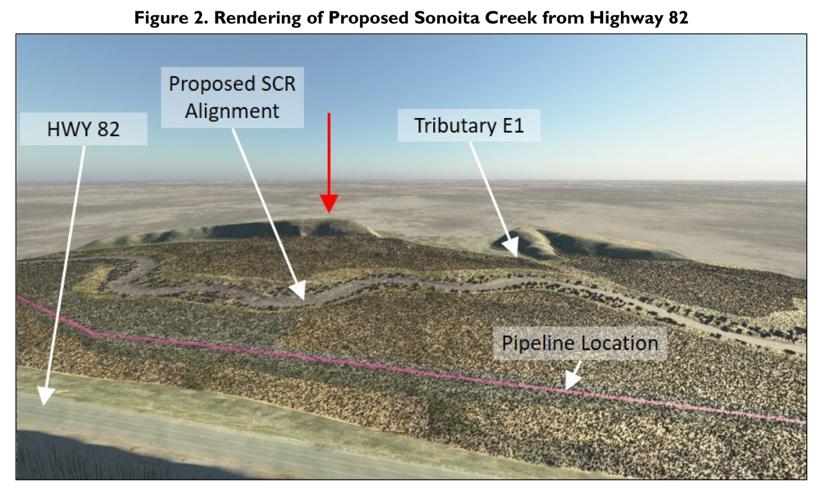

Hudbay describes the plan as “comprehensive manipulation” to the Sonoita Creek channel. The work will repair historic straightening and ongoing deepening of the creek, covering 16,352 feet in two separate sections, and reconnecting it to the floodplain. It will also move some sections of the creek several hundred feet closer to undeveloped areas and away from Arizona 82 and a natural gas pipeline, which restrict its natural movement, Hudbay said. The goal is to re-establish the creek’s traditional behavior.

Currently, Sonoita Creek is fairly intact at its downstream end on the Sonoita Creek Ranch, but degraded elsewhere on the ranch, the Corps said. For one, there’s a heavily deepened section along the highway in which concrete, metal mesh baskets filled with rock and other materials, and car bodies are used to stabilize its banks.

Today, “Sonoita Creek flows through an impaired, incised, straightened, bermed and armored reach,” but this plan offers a “unique opportunity to return a major Santa Cruz River tributary to its historic floodplain,” Hudbay has said.

The Wrong Watershed?

The EPA finds a “serious deficiency” in the plan, because Sonoita Creek lies in a separate watershed from the mine and the Cienega Creek watershed, a highly fragile ecosystem where the federal agency expects the mine’s most severe damages to occur. The mitigation plan won’t offset impacts to fish, wetlands and other resources within the Cienega watershed, the EPA said.

“By any measure, the Cienega Creek watershed supports one of the most exceptional and unimpaired aquatic ecosystems remaining in the American Southwest. As a result of the project this watershed will experience significant, permanent unmitigated impacts to its aquatic environment,” the EPA said, undoing decades of public efforts to protect both drinking water and sensitive aquatic resources.

It’s generally best that mitigation be in the same watershed and improve the same type of habitat that’s impacted, added Matt Kondolf, a University of California, Berkeley, environmental planning professor and a consultant who critiqued an earlier Rosemont mitigation plan for the EPA and the current one for Save the Scenic Santa Ritas.

“Otherwise, the ‘mitigation’ risks being irrelevant for the habitats being impacted,” said Kondolf, who spoke for himself in his response to the Star.

But the EPA’s comment reflects a frequent and inaccurate theme pervading its comments on this plan, Hudbay said in its January 2018 response to the EPA.

“That is, because the proposed mitigation does not somehow undo the modeled, potential impacts of the Rosemont project, that the mitigation is somehow inappropriate,” Hudbay said.

While Rosemont recognizes that the Corps and the EPA prefer mitigation to occur as near to the impacts as possible, the agencies’ rules allow for mitigation away from a project site, and the Corps requires applicants to increase their mitigation work in such circumstances, Hudbay said.

In its analysis, the Corps said the Cienega and Sonoita Creek watersheds are within the larger Santa Cruz River watershed, and that the Santa Cruz is the nearest legally declared navigable waterway to the mine site. So the mitigation will benefit the nearest navigable river, the Corps said.

Ecological justification

This plan doesn’t have any, said the EPA. Comparing aerial photos from 1935 and now indicates that a major stretch of Sonoita Creek in the mitigation area hasn’t been straightened and has remained stable for at least 82 years, the agency said.

Site visits and aerial photography indicate at one of the two ranches Hudbay owns, the existing Sonoita Creek channel and adjacent floodplain provide undisturbed buffer land and wildlife corridors that connect to high-quality, publicly owned grassland and woodlands, the EPA added.

Mining proponents haven’t made a scientifically sound case that filling the existing channel of Sonoita Creek and replacing it with a very curvy channel would constitute “restoration,” nor that these manipulations would compensate for the mine site’s lost habitat or from filling Sonoita Creek’s 8.9 acres, consultant Kondolf added.

But in its response, Hudbay noted that Sonoita Creek’s current location isn’t natural, having stemmed from an historic realignment and straightening to accommodate farming and infrastructure such as Arizona 82 and the pipeline. The creek’s location there exacerbates its problems of erosion and deepening, and prevents the channel from behaving like a natural stream, Hudbay said.

Past human manipulation of the creek has prevented riparian plants and a functional floodplain from being established, it added.

Agreeing, the Corps said the proposed rehabilitation and preservation would ensure the area’s long-term protection and eliminate adverse impacts.

“The proposed mitigation would improve flood control, water quality, and habitat functions of Sonoita Creek at the project site and downstream,” the Corps said.

Three tributary connection

Three tributary washes lying east of Sonoita Creek no longer flow into the creek because a road cut them off, Hudbay said. The company will remove the road, letting the washes reach the creek, Hudbay said.

But the EPA said aerial photos dating to 1935 show that the washes “are not naturally characterized by discharges” that reach Sonoita Creek, and that they wouldn’t reach the creek unless artificial channels were built. The washes also end before reaching the road, the EPA said.

Also, because several soil repositories will be built nearby, the restored channels will quickly fill with sediment that erodes from them, because it’s reasonable to expect elevated erosion levels there, the EPA said. So they won’t be sustainable.

Hudbay told the Corps the road in question is about 5 feet higher than the land to the east where the tributaries come from, and that no culverts exist to convey runoff from the road to Sonoita Creek.

Reconnecting the washes to the creek “will re-establish natural continuity” for stormwater and sediment movement into the creek’s valley and trigger a more diverse and natural ecological condition providing substantial ecological benefit, Hudbay said.

The Army Corps said that a 1947 U.S. Geological Survey topographic map clearly shows a hydrological connection between the tributaries and the creek.

Public review or lack thereof

When Augusta Resource Corp., the mine’s previous owner, applied for its Army Corps permit in 2011, neither the application nor the public notice the Corps posted about it had any detailed information about the mitigation plan. Since then, there have been no other public notices about the plan.

The Corps performed an environmental analysis of the plan as part of its permit approval, but took no public comments on that analysis, as agencies often do before making a decision.

Because of that, Pima County officials said the agency hadn’t provided enough public notice to allow for detailed review of the plan.

Such notice is legally required, and, “must include sufficient information to give a clear understanding of the nature and magnitude of the activity to generate meaningful comment,” Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry said in December 2017 comments.

The Corps said no additional public notice is required by the agency’s regulations or operating procedures. But despite that, the agency has received and given Hudbay a chance to respond to numerous letters criticizing the plan from the project’s opponents, the Corps said.