Thelma the tortoise hasn’t been seen in more than 15 years, but her legend lives on at Saguaro National Park East in Tucson.

Most Monday afternoons, park volunteer Robert Callahan tells the tale for visitors who marvel at Thelma’s epic, two-year trip from the park in the Rincon Mountains to the Santa Ritas and back again.

The 75-year-old retired business professor from the Seattle area said he created his educational program about the well-traveled reptile three years ago because he could hardly believe the story himself.

“The public really responded to Thelma like crazy. They just went bananas,” Callahan said.

So why are people still talking about a long-gone tortoise after all these years?

Because her journey still ranks among the longest ever recorded by her species.

A long way to go at turtle speed

Between August 2000 — when a radio transmitter was attached to her shell as part of a telemetry study — and August 2002, Thelma covered about 23 miles of straight-line distance. And that does not include the parts of her trip where she hitched a ride with humans, who helped her get past fences, railroad tracks and Interstate 10.

Along the way, she spent one winter on private property somewhere on the southeast side and a second winter at the northern end of the Santa Rita Mountains. Then she headed back in the direction she had come.

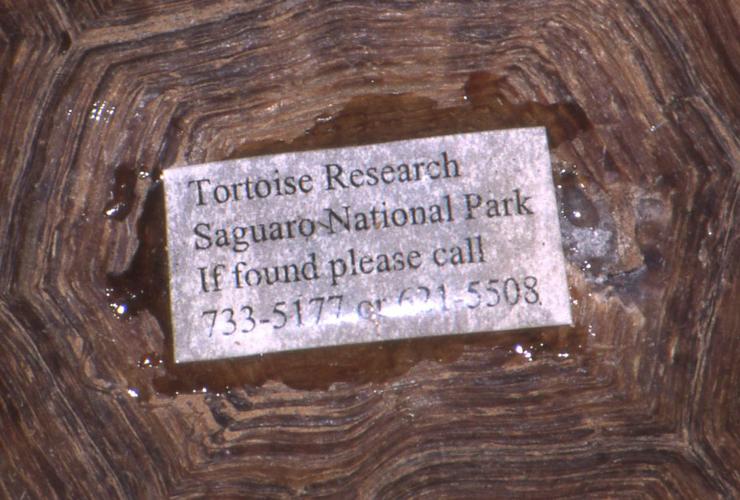

When a family found her under an overpass on I-10 in 2002 and called the phone number glued to her shell, researchers decided to give her a lift back to her original release point at Saguaro National Park.

Callahan said he gained a whole new appreciation for Thelma as he researched her travels for his presentation. He even tried to retrace her route, stopping to get down on the ground and take tortoise-level photos of some of the places she had been.

It wasn’t easy, Callahan said. “Those places don’t now exist the way they did 20 years ago.”

A tortoise that broke the mold

Which brings us to the moral of Thelma’s story: Some animals are wired to roam, but they face an increasing number of obstacles thrown up by humans along the way.

“As our sky island area gets broken up, it gets harder for animals to move around the landscape,” said Don Swann, a biologist at Saguaro National Park since 1993.

Swann took part in the original telemetry study and responded to some of the calls when their test subject was spotted in precarious places.

He thinks the story still resonates because Thelma defied all the usual stereotypes about tortoises being slow and conservative and unlikely to stray from their small home ranges.

“Tortoises aren’t roadrunners,” he said.

People also seem drawn to the story’s star: a mature female tortoise, named after one of the lead characters in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” about two women who abandon bad relationships to hit the road.

More man-made barriers blocking the way

Eric Stitt was happy to hear about Callahan’s educational program on Thelma.

He said he used to do Google searches for Thelma the tortoise every now and then, and it looked like her story had mostly faded away in recent years.

Stitt was part of the original research team that tracked the wandering tortoise, and he co-wrote the scientific paper about her unusual trip that made headlines 15 years ago.

Perhaps as few as one tortoise in a generation will venture so far from its home range, possibly to share genetics with neighboring populations.

“They’re supposed to be sedentary animals, just sitting there in their burrows and sticking to their little neighborhoods,” said Stitt, who now works as a herpetologist for an environmental consulting firm in Northern California. “We thought it was interesting that we caught the one out of however many” that was different.

But while he’s glad people are still talking about Thelma, he’s not sure if anyone is paying attention to the lesson she has to teach.

“We’re too shortsighted and too confident that our problems are going to be solved in the future,” Stitt said. “(Thelma’s story) is a really apt analogy for Tucson and most of the Southwest. We’re just carving it up and developing it.”

After brief fame, a return to private life

Callahan is a bit more optimistic. Judging from the reactions he gets to his program on Thelma, he said people seem open to learning more about “the way the park and its wildlife interacts with the rest of Tucson.”

Swann sees it, too, and not just here in Southern Arizona.

“I think there’s a rising sensitivity that connectivity is important to animals. (Travel) corridors are important to animals,” he said.

As for Thelma, she spent the winter of 2003 not far from where she was released back into the national park after her travels. Researchers lost track of her for good a short time after that, when her transmitter failed for the last time.

But Swann said just because Thelma hasn’t been seen in a while doesn’t mean she’s dead.

After all, tortoises spend most of their lives underground, and the ones that reach adulthood can live for decades.

“I think there’s a good chance she’s still alive in the park,” Swann said.

Or maybe she just went for another walk.