After living a lifetime of conflict in Afghanistan, and fleeing as a refugee with his family to Iran in 1986, Mohammad Barbari is now living a life of peace.

It is peace and happiness that fills the 85-year-old man’s heart. He is living a dream in a five-bedroom house the family is buying in a new subdivision in Oro Valley. He smiles as he looks at lush desert and nearby mountains.

“Thank you, America. My family is in a good community and a good and safe country,” said Barbari in Dari. “I am so happy to be here, and I am proud of my daughters for their hard work that has led to this house and life.” The family plans to apply for citizenship in November.

Barbari and four daughters arrived in Tucson in 2017, resettling here through Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest, a Tucson refugee resettlement program that is expected to receive 25 Afghans this month. It will be the first wave of Afghan refugees in the city since the U.S. completed its withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan in August, ending a 20-year war. The Taliban took over the country in days.

Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest and International Rescue Committee, the only other local refugee resettlement program at this time, have told authorities that both programs combined can receive up to 500 Afghan refugees in Tucson. It is unknown how many will be sent here.

In an earlier interview, Connie Phillips, president and chief executive officer of Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest, said refugee resettlement programs used to work with 95,000 refugees a year across the country, but the numbers were lowered, and last year the official cap was set at 18,000; however, the U.S. welcomed fewer than 12,000 people. Over the years, resettlement programs disbanded. Now, the government is working on relationships with housing, employers, school districts and congregations to reactivate all of the systems to work with this latest influx of Afghan refugees.

Once the refugees are relocated in the United States, 6,000 to 10,000 people per week are expected to be taken across the country to resettlement programs in various states, and 54,000 are expected to be resettled.

For the incoming Afghan refugees to Tucson, Barbari’s message is: “You can have a nice life here. Follow the laws. America is a good and safe place for you and your children.”

The Barbari family has struggled and experienced a long, horrendous journey to make it here. It began 35 years ago when they fled from their homeland of Daykundi in Central Afghanistan with a caravan of other families fearing violence by Soviet forces and Islamic militant factions. The families trekked for weeks with little food and water to reach Iran. They rested for days in Pakistan and bought more food and water to continue their journey. The thirst and hunger were the worst, but the water and dried fruit and bread had to stretch until they reached their final destination, which was over 1,600 miles from Daykundi, said Marzieh Barbari, who has heard the stories.

In Daykundi, Mohammad Barbari and his wife, Sakina, who has since died, worked for a landowner as farmers growing vegetables and wheat, and raising sheep and cows to support their then six children. They left all their belongings behind and walked, carrying a newborn and a 1-year-old who suffered from scoliosis back pain. At night, it was common to fall down because of the uneven roads with holes, and in one instance the newborn ended up in a hole when her mother fell. All searched for the uninjured baby, who was Marzieh.

Mohammad Barbari, 85, center, surrounded by his daughters (from left) Razieh, Fatemeh, Soghra and Marzieh in their home in Oro Valley.

After arriving in Tehran, the family received help from an Afghan family who was settled there, and eventually the Barbari family moved into a one-bedroom apartment. It was difficult for refugees to get work permits, a phone, a driver’s license or a house. Mohammad and his wife found jobs as farmers, and their children eventually went to school and also did farm work as they grew older. Years later, daughter Soghra Barbari went to work as a photographer and a videographer and sold cameras for a company, and Marzieh worked as a seamstress in a factory and also as a pharmacy technician. They managed to eke out a living.

The sisters recalled their mother’s death 20 years ago.

“She was vomiting blood for two nights, and she died in a hospital in Iran. The doctor never told us what happened, or why she died. He dismissed us,” said Marzieh. “She is buried in a cemetery in Iran. Maybe the doctor dismissed us because we were refugees. Refugees are not treated well,” said Marzieh.

According to a report by Oxfam International, which is a charitable organization focused on alleviating global poverty, between 1978 to 2009, millions of Afghans were killed and millions were forced to flee to Iran and Pakistan because of war and conflicts that caused death, destruction of property and sank the country’s economy.

Among those refugees were the Barbari family, who desired basic human rights and services such as education and health care in Iran.

“Iran wasn’t safe for refugees. It was so hard to live,” said Marzieh.

It took Mohammad Barbari and most of his family — all refugees in Tehran — 14 years with the help of the United Nations to meet officials in the U.S. Embassy in Romania to get processed to come to the United States under the refugee resettlement program. Two daughters and a son of Barbari’s remain in Iran with their families because they were denied approval by Iranian officials to travel to Romania for processing to the United States, said Marzieh. The family also has relatives living in Afghanistan.

When the family arrived in Tucson four years ago, they lived in a two-bedroom apartment in midtown.

“We were very happy and comfortable,” said Soghra, explaining all enrolled in English classes and looked for work with the help of Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest. They also made close friends at St. Francis in the Valley Episcopal Church in Green Valley where the congregation prayed for the family, welcomed them into the community, continue visiting and showing them Tucson.

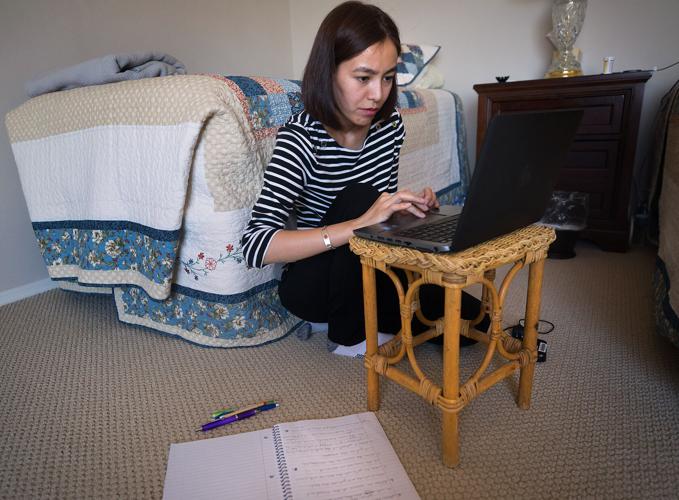

Razieh Barbari, 31, takes an English speaking class through Pima Community College and studies for her test in her room in Oro Valley. Barbari, her father and three sisters are originally from Afghanistan and arrived in Tucson as refugees in 2017.

“In this country, you can make a good life by working hard and having skills. You have a chance to buy a home and car and make a life,” said Soghra, who currently works at a local hospital. She puts in long hours and works overtime covering other shifts when needed. She also is enrolled in phlebotomy classes at Pima Community College’s Desert Vista Campus.

Marzieh works as a caregiver and has a second job as a seamstress at a bridal shop. She, too, puts in long hours and earns overtime. One day, she hopes to own a clothing alteration shop, and study pharmacy.

“We are alive,” said Marzieh, explaining that undergoing decades of hardships and persevering made them stronger. “We are here in America and are safe and happy.”

Fifteen people from six countries took the oath of allegiance during a naturalization ceremony at the Tumacacori National Historical Park, about 50 miles south of Tucson, on September 17, 2021. It was their final step in becoming U.S. citizens. The ceremony was part national Citizenship and Constitution Days. Video by: Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star