How much critical habitat for jaguars will be eliminated remains unclear more than a month after a court decided the U.S. government erroneously designated land, including the proposed Rosemont Mine site, as legally protected habitat.

Depending on how the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service interprets the ruling, as little as 8.8% or as much as 51% of all 709,000 acres of critical habitat in Southern Arizona mountain ranges for the endangered jaguar could be eliminated.

The May 17 ruling from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a wildlife service decision that designated the land surrounding the proposed Rosemont Mine site in the Santa Rita Mountains as critical jaguar habitat. But the ruling’s wording left it unclear in some observers’ views as to how much total land will be removed from critical habitat.

The outcome could have significant legal ramifications because federal law prohibits destruction or “adverse modification” of critical habitat for endangered species.

In 2014, the wildlife service formally designated jaguar critical habitat, but the same year it determined the mine would not illegally destroy critical habitat.

But U.S. District Judge James Soto in Tucson overturned that decision in February 2020 and ordered it redone. The 9th Circuit declined to rule on that issue since it has decided the critical habitat itself wasn’t properly designated.

A wildlife service regional spokesman in Albuquerque, Al Barrus, declined to say how the agency intends to interpret the decision.

Seven adult male jaguars have been spotted in the U.S. Southwest since 1996. Five have only been seen in Arizona, one only in New Mexico and one in both states.

Hudbay says impact is limited

At issue is the future of two major areas of jaguar critical habitat, known as Unit 3 and Subunit 4b. Unit 3 spans about 351,500 acres, and Subunit 4b covers about 12,710 acres.

All of Subunit 4b of critical habitat would disappear regardless of how the 9th Circuit ruling is interpreted by the feds, but the amount of land that would be removed from Unit 3 remains up in the air.

Unit 3 runs in almost a straight shot south from the Santa Rita Mountains, through the Patagonia, Huachuca and Empire mountains, south to the Canelo and Grosvenor hills near the U.S.-Mexican border. Subunit 4b covers much of the Whetstone and Empire Mountains southeast of Tucson and south of Benson.

The Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson.

Hudbay Minerals Inc. is the company proposing to build the mine, which it no longer calls Rosemont but has folded into its larger Copper World project in the Santa Ritas.

Hudbay said the court decision limits the area to be removed from critical habitat to only the 50,000 acres that includes the Rosemont site at the north end of Unit 3 of jaguar habitat, and the 12,710 acres of Subunit 4b.

The Toronto-based mining company specifically referred to a footnote in the recent ruling. It noted, in referring to the wildlife service’s original determination that some critical habitat was occupied, that Hudbay was only contesting critical habitat for the northern Santa Rita Mountains area of Unit 3 — roughly 50,000 of its total of 351,000 acres.

Others find ruling unclear

But Marc Fink, an attorney for the environmental group that supported the service’s designation, the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity, said the 9th Circuit ruling left it unclear whether only the 50,000 acres or whether all 351,501 acres of unit 3 would be removed from critical habitat.

“It’s a great question. It’s something we’re still assessing and trying to figure out if there’s steps we want to take on this,” Fink said.

He added, “there are too many attorneys in the room” for the center to make a quick decision on how to react to the conflicting interpretations of the 9th Circuit’s ruling.

Steve Spangle, a retired Arizona field supervisor for the wildlife service, agreed the ruling is unclear. He said that if he were still on the job, “I would look at the whole designations and decide what if any modifications should be made, or should we just start all over?”

“We had a competent biologist on that designation. I would ask her to take a whole new look,” said Spangle, who oversaw the wildlife service’s Arizona Ecological Services office when it made the original critical habitat designation in March 2014. He retired in 2018.

The wildlife service biologist to whom Spangle referred, Marit Alanen, still works for the agency in its Tucson office.

Failed to prove ‘essential’ need

The 9th Circuit ruling said repeatedly that the service’s designation of the entire Unit 3 was “arbitrary and capricious,” a phrase courts typically use when they overturn or toss out a federal agency’s action. The ruling was handed down by a three-judge panel. It voted 2-1 to overturn a separate part of Soto’s ruling that had upheld the critical habitat designation of all of Unit 3 and Subunit 4b.

The 9th Circuit panel majority found the service failed to make the case that those areas were “essential” to conservation of the jaguar — a standard required by federal law to justify designation of unoccupied critical habitat — which is how this land had been designated by the service.

“In sum, the FWS has not provided a ‘rational connection between the facts found and the choice made’ or ‘articulate[d] a satisfactory explanation’ to justify its designations of Unit 3 and Subunit 4b as unoccupied critical habitat,” the panel wrote.

But the ruling simply reversed Soto’s upholding the designation of the “challenged area” as critical habitat. The “challenged area” referred to the area of critical habitat that Toronto-based Hudbay had originally challenged: the 50,000 acres in Unit 3 and 12,710 acres in Subunit 4B.

The wildlife service can’t comment on the ruling’s implications because it still considers the case pending, said Barrus. Asked why, Barrus referred a reporter to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Phoenix.

There, a U.S. attorney’s spokeswoman in turn referred the question to Shannon Shevilin, a spokeswoman for the Justice Department’s Environmental and Natural Resources Division, who didn’t return an email from the Star seeking comment. Typically, U.S. Supreme Court rules give losing parties in a Circuit Court ruling 90 days to file an appeal to the high court.

This court-based repudiation of jaguar critical habitat is the second such instance since jaguar habitat was designated in 2014. In February 2022, the wildlife service removed about 59,000 acres of critical jaguar habitat in New Mexico after the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the agency’s previous designation of that land as jaguar prime habitat.

The 10th Circuit’s rationale was similar to that of the 9th Circuit’s last month: that the wildlife service failed to show the lands in question were essential for jaguar conservation.

More recently, in December 2022, the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the wildlife service to establish a much more expansive jaguar critical habitat of more than 14 million acres in the “Sky Islands” of Northern and Southern Arizona and in Southwest New Mexico. A sky island is a forested mountain that rises up out of intervening desert and grasslands, the Sky Island Alliance says.

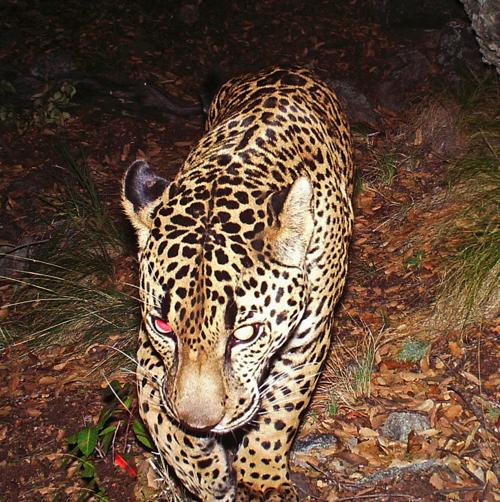

A male jaguar not previously detected by researchers was videotaped just three miles south of the recently constructed border wall between Mexico and the United States.

The jaguar appeared for the first time on camera traps along the riparian corridor of Cajon Bonito in Sonora, Mexico. The lands where the jaguar was recorded have been managed by the Cuenca Los Ojos foundation to preserve and restore biodiversity during the last three decades. Researchers have dubbed the jaguar El Bonito.

Credit: Ganesh Marin, the project leader, is a Ph.D. student in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment at the University of Arizona and a National Geographic Early Career Explorer. The research project is a joint effort of the University of Arizona and the University of Wyoming in collaboration with the Cuenca Los Ojos Foundation and members from Santa Lucia Conservancy, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Phoenix Zoo and Arizona State University.