Gov. Doug Ducey is backing a legislative proposal to end a longstanding ban on giving food stamps to drug felons.

Advocates, including Ducey, say it will give much-needed help to people recently released from prison and jail. The change would not cost the state any money, as food stamps are federally funded.

The Pima County Attorney’s Office in Tucson instigated the effort to lift the ban, which has long been criticized as unfair for singling out drug offenses. It does not apply to people convicted of other kinds of crimes.

“We now know that substance-abuse disorder is a health issue that we need to treat as such,” said Christina Corieri, senior policy adviser to the Republican governor. “When people leave prison, violent offenders are automatically eligible and must be, by federal law, for these benefits. But people who have had a drug charge are not.”

Ducey expects the change to save the state money in the long run by reducing the chances that drug offenders will be locked up again.

“People who leave prison already have a difficult time getting a job. We don’t want people to resort to subsistence crime,” Corieri said.

The ban is the result of a federal law passed in the mid-1990s during the so-called “War on Drugs.”

The law always allowed states to opt out, and Arizona is now one of a handful of states still enforcing it. That means anyone in Arizona convicted of a felony drug offense after Aug. 22, 1996, is banned for life from enrolling in the state’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SNAP, which is for low-income people, is still often informally referred to by its former name, food stamps.

Just four states still have such a lifetime ban in place, an August 2016 Congressional Research Service report says: Arizona, Mississippi, South Carolina and West Virginia.

Lifting the ban embraces the Republican philosophy of personal responsibility, Corieri said.

“It is requiring something on their behalf. They need to engage in treatment if that is something that is medically necessary for them,” she said. “And it does have the authority for DES (the Arizona Department of Economic Security) to verify that through drug testing as well.”

Legislative support

The measure is part of House Bill 2372, which includes several changes to public assistance in Arizona, including restoring some cuts to Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), also known as welfare. The changes to welfare have received most of the attention and public discussion about the bill.

The House passed the bill 31-29 Thursday night. Similar legislation is expected to be considered in the Senate.

There’s no estimate of how many people would be added to the SNAP program if the measure to lift the drug-felon ban becomes law. In the last state fiscal year, 3,758 people applied for food stamps through Arizona’s SNAP program but were denied because of felony drug convictions, the Governor’s Office says.

But Corieri said it’s possible that the ban affected more people than the numbers reflect — some just don’t apply because they are aware of the ban.

The program is entirely funded through federal dollars and in January covered 941,321 Arizonans, including 450,654 children, at a monthly cost of $113,285 million. The average family receives $269 per month or about $3.20 per meal and is enrolled in the program for 23 months.

The House bill’s language calls for people convicted of drug felonies to meet some conditions before they could qualify for food stamps, including agreeing to random drug testing and substance-abuse treatment unless a medical provider says it’s not necessary.

“I think that the message overall of the governor’s State of the State (speech) and his agenda moving forward is creating more opportunity for people, and the people who need help the most are those, in many cases, struggling to get back on their feet,” Ducey spokesman Daniel Scarpinato said.

“He sees these reforms as pretty common sense and also rewarding good behavior. ... If people are trying to get their life back together, going through drug treatment, that is the kind of behavior that we want because it’s going to make our state a better place and it’s going to improve those peoples’ lives and their families’ lives.”

Food bank support

Though she would rather see the ban on drug offenders lifted with no conditions or strings attached, it is a step in the right direction, said Angie Rodgers, president and CEO of the Association of Arizona Food Banks.

“For an individual who made a mistake in their life, banning them from ever receiving assistance makes it difficult to get back on your feet,” Rodgers said. “Having a second sentence of not being able to receive help seemed excessive.”

The Pima County Attorney’s Office also wanted the ban to be lifted without any conditions like drug testing attached, said Kathleen Mayer, the office’s chief legislative liaison.

But the measure is “certainly better than what we had before, which was nothing,” Mayer said.

“We are really trying to encourage people to break the cycle of addiction and reintegrate into society. ... Whatever we can do to keep them from sliding back,” she said. “It is very difficult for folks to essentially start all over.”

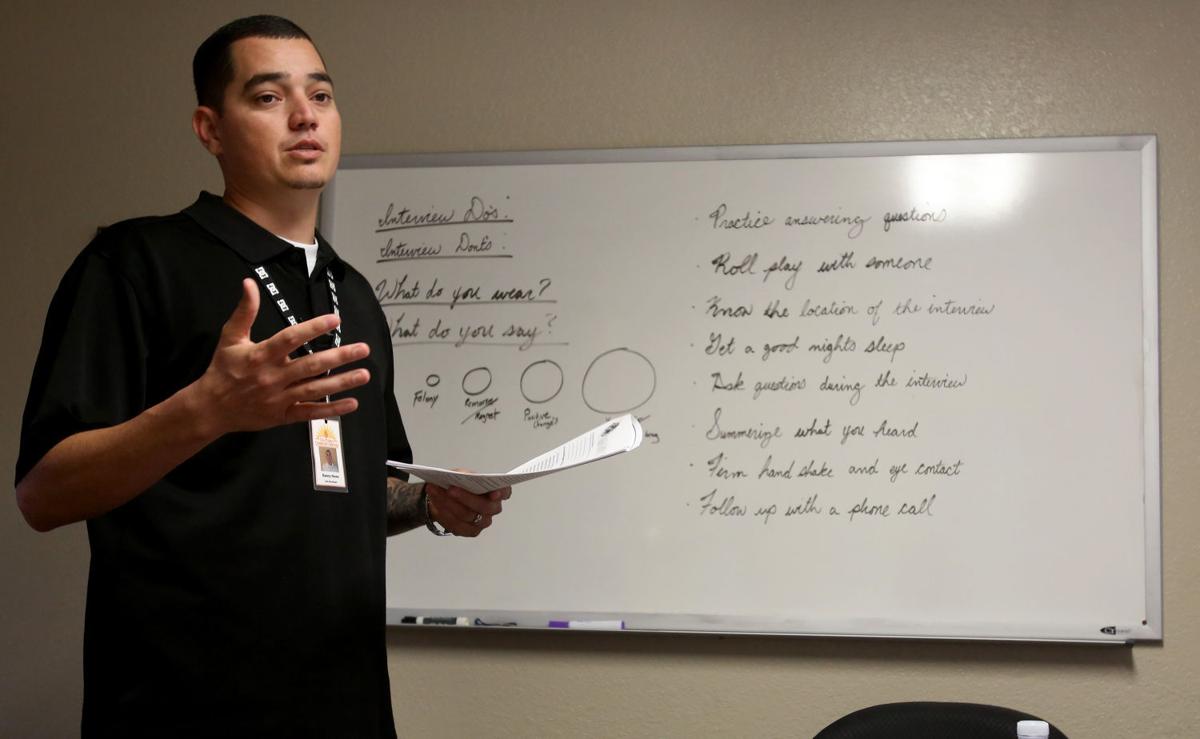

Danny Howe operates two Tucson transitional homes for men who have been released from jail or prison. Food is not covered and getting it can be a roadblock, said Howe, who is a member of the local Second Chance Coalition, which aims to help former inmates reintegrate into society.

Howe, 33, spent three years in prison, and a drug conviction prevented him from getting food stamps. He was working two low-paying jobs, typically working 12 hours per day busing tables and assisting a cabinetmaker to support his family, which includes two children.

“My family struggled,” he said.

In the transitional housing he operates, he now tries to ease the struggles for others. He charges them $100 per week to live in one of the houses. Utilities are included in that price, but food isn’t.

Some of the men can go to the local food bank or get free meals from churches and other charities. But time and transportation problems can make that logistically difficult for people trying to get back on their feet, said Calynn “Wrenn” Forrest, 30, who lives in one of Howe’s homes.

“When I got out of jail I was terrified I’d be homeless again,” said Forrest, who was released from jail in October after being convicted of burglary and a drug offense.

Forrest says he’s fortunate his drug conviction was reduced to a misdemeanor, rather than a felony.

That means he’s now able to get food stamps to defray his expenses. He’s working as a restaurant server across town from where he lives. On weekends it takes him three hours by bus and bicycle to get to his early shift at work.

He loves to bake and often shares the groceries he buys with his food stamps with the other men in the house.

“Because you were a drug addict, why should you not be able to eat?” he asked.

Highly political

Officials with the County Attorney’s Office estimate that at any given time there are about 300 people going through Pima County Superior Court for first- or second-time felony drug offenses.

Right now the county is able to offer people in its Drug Treatment Alternative to Prison program short-term food vouchers through a federal grant. But the grant money is set to run out Sept. 30, Chief Deputy County Attorney Amelia Cramer said.

“This is to get people over the hump to being clean and sober, to help them to succeed,” Cramer said. “The way to make this perpetual for those participants is not two- or three-year grants, but to have this exemption to make them eligible. Our fear is if they are hungry and have no legal form of income, they are going to steal things to buy food.

“There is a gap time when they get out of jail or residential treatment and they don’t always have a job right away.”

Arizona is one of 10 states that doesn’t allow people with felony drug convictions to get Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Congressional Research Service report says. There’s no proposal to change that restriction at the moment.

“We would like to see all sorts of public benefits available to people with felony drug convictions,” Cramer said. “It’s highly political. We’ll take it one step at a time.”