Update: The Sonoran Attorney General has announced that police made an arrest in the killing of Santiago Barroso. The accused murderer, whose full name was not released, killed Barroso over a personal conflict related to romantic relationships, not Barroso's work as a journalist, the attorney general said. Read more here.

On the morning of July 16, 1997, I alerted the Star city desk to shocking news I’d read online in Sonoran newspapers.

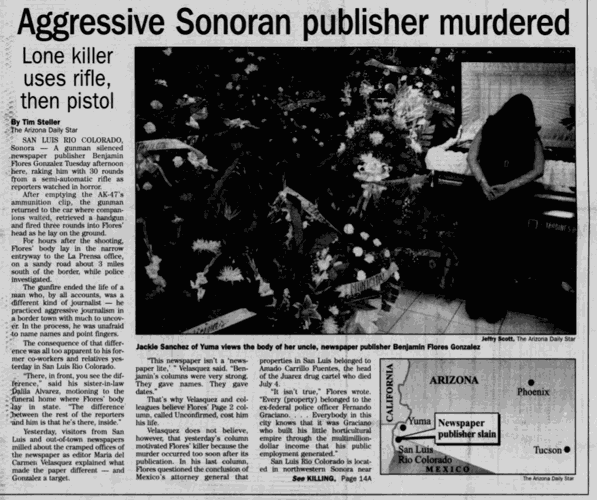

The muckraking young publisher of a newspaper in the border city of San Luis Rio Colorado, Benjamin Flores Gonzalez, had been assassinated in a barrage of gunfire outside his office the previous day.

The Star newsroom response was swift — and expensive. The city editor chartered a plane that photographer Jeffry Scott and I took to Yuma, where a rental car was waiting for us. We drove across the border and produced days of front-page stories.

Last week, another journalist was killed in San Luis Rio Colorado. The difference in the response and in the atmosphere surrounding the murder reflects dangerous changes in the condition of the free press — not just in Sonora and Mexico, but in Arizona and the United States, too, and around the world.

It shocked no one that a journalist could be killed in Sonora, although Santiago Barroso was perhaps a surprising target. He hosted a morning radio show, taught journalism in a university and wrote a column that recently had touched on smuggling. But he was not the in-your-face writer that Flores Gonzales had been at his newspaper La Prensa, where Barroso worked with Flores Gonzales in the 1990s.

Yet he was the second Sonoran reporter to be killed this year — radio announcer Reynaldo Lopez was shot and killed in an attack that officials concluded was a case of mistaken identity.

Nationwide in Mexico last year, four journalists were confirmed to have been killed because of their work, and six others were killed in cases where the motive was unconfirmed. In the most notorious case since Flores Gonzalez’s death, Alfredo Jimenez Mota, a reporter for El Imparcial newspaper working on drug and corruption stories, disappeared and was presumed killed in 2005.

Jimenez Mota’s death, too, prompted numerous stories on both sides of the border. But Barroso’s murder last week barely registered in Arizona or elsewhere in the United States. And we certainly didn’t charter a plane to cover the story.

This newspaper and most others that are not national publications have shrunk or disappeared as the newspaper advertising base has deteriorated; just last week, for example, the Star announced it is cutting 60 printing and packaging jobs, as the newspaper will be printed in Phoenix and trucked to Tucson to save money.

Under these economic conditions, we’ve also been forced to choose more carefully when to splurge on in-depth news coverage hundreds of miles from our main market.

Ironically, it was Facebook that made clear last week just how bad the local-news situation has become in the United States. In planning for a new product, called Today In, Facebook assessed which places in America have outlets producing five separate local-news stories per day that could be republished for their new product.

Facebook, which of course has wrenched away many of the advertisers that news outlets used to rely on, found that about one in three American Facebook users now lives in a place where there is not enough local news being produced to launch Today In. The “news deserts” that Facebook helped create are now forcing Facebook and others to try to reinvent local news.

But any new journalistic efforts are facing heavy headwinds, blown by the growth of authoritarianism around the world, and by the same crumbling economics of professional news-gathering.

The murders of Mexican journalists stem in part from particular national features of impunity and organized crime, but they are also connected to the declining financial and political viability of independent journalism, as Jan Albert Hootsen, the Mexico representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, explained to me.

“Journalism across the world is in a very severe economic crisis,” Hootsen said. “That makes journalists more vulnerable as well.”

“It takes away economic certainty, it takes away benefits, it takes away institutional support,” he said.

In Mexico, about 1,000 journalists have been laid off in the last five months, he said. For many, like Santiago Barroso, they put together a living working a variety of relatively low-paid gigs. Barroso managed to be the breadwinner for his wife and two kids, though.

While in Mexico the primary threats come from organized crime or politicians tied to the underworld, authoritarian politicians and their clans also pose a threat there and around the world.

Luis Alberto Medina was a host of a radio program on a popular station in Hermosillo, Sonora, till 2017. Then, pressures from businessmen connected to the state’s ruling party forced him off the air. Medina then established Proyecto Puente, an online-only news outlet supported by sponsors, but he eventually came under new threats, direct and indirect.

This year, people aligned with Gov. Claudia Pavlovich and the other powers of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, such as former governor Manlio Fabio Beltrones, have ramped up their pressure against Proyecto Puente, Medina told me. An anti-corruption prosecutor aligned with the governor recently issued him an order to appear based on a faked criminal complaint. Failure to respond to the anonymous complaint could have landed Medina in jail.

“They started with smear campaigns via social networks. Seeing that those didn’t work, this government sharpened the tone and they started inventing legal claims against me,” Medina explained to his audience March 7.

“If this is going to lead me to jail, tell me, governor, where my cell is,” he said.

It may seem like a distant threat if you’re living north of the border, and maybe it is when it comes to governors. But President Trump, on the other hand, represents a real threat to journalism across the country and, by his demonstration effect, around the world.

Trump has turned a significant portion of the country against legacy journalism institutions like newspapers and TV networks, by labeling us “fake news” and “enemies of the people.” Trump talked about jailing journalists to send a message against government leaks, according to former FBI Director James Comey. And the president praised a congressman for his “body slam” of a reporter.

He’s also set off some unstable Americans: Last week a Florida man pleaded guilty to sending pipe bombs to CNN as well as a dozen other perceived critics of the president.

But his worst effects so far may have been abroad.

“It has been the position of the Committee to Protect Journalists for quite some time that the rhetoric of Donald Trump of the media as the enemy of the people is something that has been adopted by government and rulers in other countries,” Hootsen told me. “It’s been used as an excuse to crack down on critical media.”

So here in the United States, Trump may only be helping accelerate the financial erosion of formerly robust, now feeble, journalistic institutions. Overseas, in countries like Egypt, Turkey, Venezuela, the Philippines and Nicaragua, authoritarian rulers take Trump’s rhetoric as further permission to jail journalists and shut down outlets.

The Russian parliament just passed a law under which people can be jailed for publishing “fake news” — that is, news showing “clear disrespect for society, government, state symbols, the constitution and government institutions.”

In Mexico, the reality tends to be more brutal: You anger a bad guy, or threaten the interests of someone powerful, and you might get killed.

Humberto Melgoza knows all about it. I got to know him in 1997, because he was working for Benjamin Flores when Flores was killed. Afterward, he founded a weekly paper called Semanario Contrasena, which still exists today. Coincidentally, the paper had been publishing Barroso’s columns until he was killed last week.

Melgoza told me that reporters can limit their risks, but risky topics can’t be avoided.

“Since we’re in an area that generates so much news, it’s impossible to avoid everything (dangerous) — but we always take a lot of care. It’s just unavoidable dealing with those topics.”

Investigators suspect that Barroso’s work is what led to his murder. Thinking back, I was at a goodbye party for colleagues who are leaving the Star and moving away from Tucson, when, 200 miles to the west, somebody knocked on Barroso’s door. He opened the door of his home and was shot.

The message, perhaps, wasn’t quite as clear as when a gunman raked Benjamin Flores with gunfire outside his office in 1997.

But it reinforced what we already know: If we want a free press in Mexico, the United States or anywhere in the world, we’re going to have to fight for it now.