Six months after Arizona became a state, Tucsonan Jeanette Done's mother fled Mexico's revolution in a journey that helped establish Tucson's first Mormon community.

Her family's flight followed a pattern by which Mormons from Mexico scattered across Southern Arizona in the state's first year.

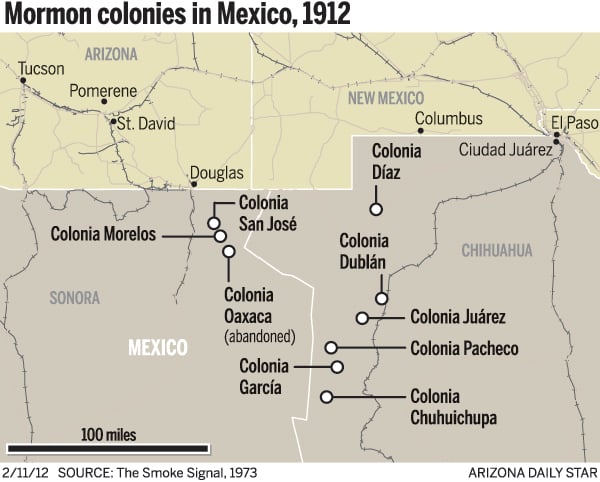

Just a 3-year-old child, Done's mother, Thora Young, was among thousands who escaped the eight Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and Sonora as fighting and lawlessness took hold around them in July and August 1912. Young, her sister and mother were among the refugees who stayed in an abandoned lumberyard in El Paso, while hundreds more later stayed in U.S. Army tents in a camp outside Douglas.

Eventually, Young's father joined her and the family settled in Binghampton, then a farming settlement at the bend in the Rillito where Alvernon Way meets the river. Other families from the Mexican colonies settled in places like Douglas, Safford, Pomerene and St. David, helping establish some communities that endured and others that died out.

It's an extraordinary family story that is becoming familiar to more Americans because of Mitt Romney's candidacy for the Republican nomination for president. Like Done's mother, Romney's father fled the Mormon colonies in Chihuahua as a child, but in Romney's case the family resettled first in Utah.

Across Arizona, people with family names such as Haymore, Naegle, Lillywhite, Fenn, Huish and Williams share the stories even today in self-published books and passed-down accounts. The stories fill Done and other descendants of this so-called Mormon Exodus with awe at the ingenuity, forbearance and community spirit of their ancestors.

"They were all very hard-working together," Done said. "They were dedicated to their church and their community, and they became quite prosperous."

POLYGAMISTS MOVED SOUTH

A U.S. government crackdown on polygamy in the 1880s drove the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to establish colonies south of the border, where polygamist families could be free from the increasing harassment of U.S. marshals.

"After the Civil War, the federal government felt they'd cleaned up the slavery issue, and polygamy was the next great sin to go after," said Carolyn O'Bagy Davis, a Tucson author who last year published "The Fourth Wife: Polygamy, Love & Revolution," a biography of a woman forced to flee the colonies.

By moving to Mexico and maintaining polygamy, the families felt they were fulfilling a religious calling that would let them attain higher glory in heaven and help them keep their multiple families together, Davis said.

In 1885, scouts from St. David and elsewhere checked out possibilities in Sonora before buying land in the plain below the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madre in northwestern Chihuahua. By the time the revolution broke out in 1910, there were eight Mormon colonies in Chihuahua and Sonora, with a population around 5,000.

The Mormons did not mix much with the local Mexican population, and tensions grew along with the increasing prosperity of the white American colonists, who quickly developed orchards, flour mills and fine brick homes. Missionary Ammon Tenney, who lived in Colonia Dublán at the time, noted in his journal that "race prejudice" existed among the Mormon colonists.

Tenney went on: "While on the other side the Mexican Element are among the most jealous and when we add our Superior intellect coupled with our advanced Prosperity it naturally irritates these Poor People, which too often Culminates in Robery with its kindred train of evils, or crimes." (Capitalization and a misspelling are repeated from the journal.)

The revolt against Mexico's dictator, Porfirio Diaz, stemmed in part from his allowing foreign investors free rein in the country. So the presence of rich, white Americans inflamed some residents and rebels, who coveted the Mormons' horses, supplies, homes and guns.

"The social fabric was unraveling," said Mike Landon, archivist at the LDS Church History Library in Salt Lake City. "It was tough for anyone, but especially for foreign nationals. It was a nationalistic revolution."

SOME LEFT BEFORE 1912

For a couple of years leading up to 1912, as Mexico destabilized Mormon families slowly trickled away from the colonies, some of them settling at Binghampton. Then battles, criminality and threats spiked at the Chihuahua settlements. On July 28, 1912, Mormon officials finally agreed to long-held rebel demands that they hand over their guns.

Though they hid a few firearms, the Mormons now felt too vulnerable to stay and made hasty plans to send all the women and children to the United States. Done's grandfather, William H. Young, stayed while Done's grandmother, Effie May Butler Young, took their two children on the freight cars of a refugee train from Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, to El Paso.

There the migrants stayed in an abandoned lumberyard.

Done's mother explained in a short memoir: "I remember my mother draping some quilts around posts to give us a little privacy. The government brought us food."

While the locals were generally welcoming, some came around to stare at the American polygamists from Mexico, although some of the families, including Done's grandfather's, were monogamous, and the church opposed polygamy by then, too.

"They felt like they were in a zoo," Done said.

A FEW STAYED LONGER

As quickly as possible, with the help of the U.S. government and fellow Mormons, the refugees looked for someplace to go while they waited out the revolution. In the case of Done's grandmother, the first stop was Utah, where she gave birth to her third child before traveling to Binghampton to await her husband there.

Like many of the men, Done's grandfather stayed longer in Mexico and held out hope for a rapid resettlement of the colonies they'd built there. But eventually most fled, often in wagon trains. He went to Binghampton for a few months, then returned to Colonia Dublán in April 1913, and in June that year, thinking the situation was safer, sent for his family in Binghampton.

"Conditions in Mexico became increasingly worse," Done's mother wrote of that time in her memoir. "The rebels were killing and stealing all the time. My father had some very narrow escapes several times. He was captured by the rebels and held hostage because he would not give up a revolver he had borrowed from a friend in Colonia Dublán."

"In 1914," she went on, "we left Mexico for good and came back to Tucson, to the little community of Binghampton."

The communities of Pomerene and Miramonte, northwest of Benson, also sprang up thanks to the settlement of Mormons from Mexico. Miramonte didn't last much more than a decade because of inadequate water, but Pomerene exists today, although it has lost its farming culture due to low water levels.

Binghampton, too, disappeared as a separate community in the 1950s, swallowed up by Tucson as it grew. But the Mormon refugees from Mexico had left a legacy that Done and others across Southern Arizona continue to appreciate.

"They didn't all get here directly, but once they were here, they were all this united community," Done said. "I felt it was a little bit of utopia."

On StarNet: See more early photos of Mormons who left Mexico at azstarnet.com/gallery

Contact reporter Tim Steller at 807-8427 or at tsteller@azstarnet.com