Voters will soon decide the fate of the largest debt financing plan Pima County has ever pursued: 99 projects that would cost taxpayers $815.7 million.

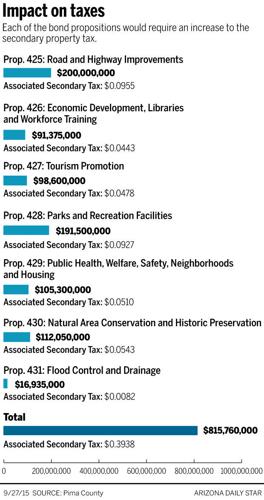

The proposals, divided into seven questions on the ballot, cover flood control improvements, open-space acquisitions, public health, affordable housing, tourism promotion, and parks and roadway improvements.

If voters approve all seven questions, taxpayers will be making payments until 2042. The total payoff: an estimated $1 billion.

With the exception of $22 million voters greenlighted in 2014 to pay for a new animal care center, the Nov. 3 election marks the first time since 2006 that the county has asked for bonds to fund a significant infrastructure or improvement project.

“It took a good eight years to get through the past projects,” said Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry. Waiting several years let the county pay off much of the previous debt before taking on new long-term expenses, he said.

Supervisor Sharon Bronson said the bond plan represents an investment in Tucson’s economy and quality of life.

“If we want this community to be vibrant and to grow and to grow jobs, we have to invest in ourselves,” she said.

But Joe Boogaart, a member of the Pima County Bond Advisory Committee and spokesman for Taxpayers Against Pima Bonds, says the price tag is higher than the county can afford

“I just don’t think it’s the right time to bond for that kind of money,” Boogaart said.

27 YEARS OF PAYMENTS

Pima County’s existing tax rate and the proposed increases the bond package would bring have raised the ire of bond opponents.

County officials and bond supporters are “flat-out deceiving people,” Supervisor Ally Miller said.

An opponent of all seven bond questions, Miller said she’s concerned with the way the tax impact of the bonds has been presented. If all seven bond questions pass, the secondary property tax would increase from 70 cents to 81.5 cents. For a house valued at $152,000, the county average, the rate increase would mean an annual secondary tax payment of $123. Without the increase, the same homeowner would pay $106 for the secondary tax.

Supporters of the bonds have used this calculation to show all seven bond questions would add $17 to annual tax payments. That calculation reflects the difference paid in the current secondary property tax of 70 cents per $100 of assessed value and what the rate would rise to — 81.5 cents.

Supervisors imposed a secondary rate cap of 81.5 cents, although state law sets no limits for secondary property taxes.

Another way the tax impact of the total bond package is calculated is by noting all seven questions would represent slightly more than 39 cents of the secondary tax. Using that calculation, the same $152,000 residential property would pay $59 annually to retire the 2015 bond debt.

This was the way the county used to explain the debt and tax picture in the bond implementation plan the Board of Supervisors recently approved. The figure represents an annual average the owner of a $152,000 home would pay over the 27-year cycle of bond repayments as the county sells the bonds over a 12-year period, taking on the new debt incrementally.

The current secondary tax rate of 70 cents pays the debt service on existing county debt. As the debt is retired, the rate declines annually. If the proposed seven bond questions pass, the county would add to the secondary rate each year with new bond sales, which is how the 81.5 cent secondary rate is met.

Pima County relies almost exclusively on property taxes to fund governmental operations. But Supervisor Richard Elías said that doesn’t necessarily make Pima County a high-tax entity.

“When you take a look at the overall taxes that people pay in other counties, it shows that we’re pretty much in the middle,” Elías said.

Maricopa County, for example, has a combined property tax rate of about $1.87, inclusive of primary, library, flood control and health care district taxes. Pima County’s combined tax rate is $5.96. But Maricopa County also charges a sale tax to fund its jail, which Pima County pays from the primary property tax.

Pima County can’t rely on the state or federal governments to invest in the region, said Supervisor Ray Carroll.

“It’s ourselves alone that’s going to reinvest in our roads and infrastructure,” Carroll said.

DEEPER IN DEBT

Pima County’s existing debt is about $1.3 billion, and bond critics say that’s another reason not to support the bond proposal.

The county carries more debt than all other counties in the state. But county officials say that doesn’t show the full picture.

“To compare us to Maricopa County like that is a little like apples to oranges,” said Pima County Supervisor Ramón Valadez.

Pima County, unlike other Arizona counties, has traditionally taken the lead in shouldering the debt for regional projects. Cities and towns in other parts of the state typically take on debt to fund local projects.

Pima County ranks second to Maricopa County in outstanding per-capita debt, Arizona Department of Revenue data show. That includes the debt of counties, municipalities, school districts, fire districts and other taxing authorities.

Some cities in Maricopa County have more debt than Pima County. The city of Cave Creek has a $10,145-per-capita debt ratio while Scottsdale’s is $5,379. Pima County’s per-capita bond debt is $1,330.

A 2012 Arizona auditor general analysis also points out the unique position of Pima County’s bond program. Many local bond projects benefit the entire county, the audit says.

“In contrast, other cities, towns and counties in Arizona follow a traditional model in which a single government jurisdiction issues general obligation bonds for a limited number of specific projects that benefit only that jurisdiction,” it notes.

That’s nothing to be proud of, said Taxpayers Against Pima Bonds’ Boogaart.

“I would prefer to have the jurisdictions take care of their own problems,” he said.

COSTLY MAINTENANCE

Long-term maintenance costs associated with bond projects are a concern of opponents — and even some supporters.

“I just can’t see taking on new projects when our deferred maintenance amount is so high,” Boogaart said.

His group estimates operations and maintenance for bond-funded projects over 25 years would cost $545 million. County officials say the figure is $315 million over 25 years.

Supervisor Miller also questioned whether South Tucson and the city of Tucson, both with longstanding financial troubles, could keep up with their obligations.

The downtown community theaters and historic cultural landscape proposal on the ballot for $23.5 million exemplifies the concerns critics have about expensive maintenance.

Proposed improvements to the Tucson Music Hall and Leo Rich Theater at the Tucson Convention Center include restoring the long-neglected landscape and fountain outside the Music Hall.

Designed by famed landscape architect Garrett Eckbo and built in the early 1970s, the city-owned fountain has fallen into disrepair. Where a series of pools and falls once flowed with water, today there is only puddled rainwater and debris.

Estimates to repair the landscape and fountain top $8 million. Annual operations and maintenance costs of the theater and fountain projects are about $150,000, county bond documents estimate.

As recently as July, Huckelberry also expressed concerns with the city’s ability to provide long-term maintenance for its public assets.

“Given the city’s lack of maintenance of key public facilities such as the Tucson Convention Center, Tucson Music Hall, the Eckbo fountains, the Temple of Music and Art and swimming pools to name a few cases, our code amendments are both appropriate and necessary to assure voters that new facilities built with bonds will be maintained and adequately operated,” Huckelberry wrote in July.

His comments were in response to concerns Tucson City Councilman Steve Kozachik raised over maintenance obligation measures the county had planned to include in the bond ordinance.

Initially, the county planned to withhold future funding for projects if past bond-funded assets fell into disrepair and were not fixed within 120 days. After opposition from Kozachik and others at the city, amendments were made to allow the jurisdictions more time to address potential deficiencies with bond-funded projects.

“We dodged a bullet,” Kozachik said. “If the original language had gone through, it would have set this region up for intergovernmental conflict for the next quarter of a century.”

FREQUENT CRITICISM

Pima County’s bond program has been the target of opposition for years.

In 2012, the Legislature passed a law that required the state auditor general to audit the county’s 1997, 2004 and 2006 voter-approved general obligation bond programs.

Marana officials lobbied the Legislature for the audit. It was a byproduct of a court battle between the two jurisdictions over a county sewer treatment facility in northern Marana.

When released in January 2013, the auditor general’s report found no fault or inconsistencies in the county’s bond programs.

“Pima County has spent bond proceeds from the 1997, 2004, and 2006 general obligation bond programs for authorized purposes and approved projects, and project changes appear to have been made without bias,” the audit notes.

At the time, Marana represented about 4.7 percent of the tax base but received nearly 6 percent of bond funding for projects in the town. Tucson, with 43 percent of the tax base, benefited from more than 50 percent of projects. Residents of unincorporated areas, also representing 43 percent of the tax base, received about 35 percent of project spending.

Marana Mayor Ed Honea voted to place the town’s projects in the current bond package despite opposing all seven bond questions.

He said the state audit did not go far enough. “What we wanted was a forensic audit,” Honea said.

Miller also said the audit, which was more than 50 pages, lacked detail.

“It’s not down to the project level,” she said.

Valadez said complaints about the audit were misguided. He noted it was done over the objection of Pima County and at the direction of the Republican-led Legislature along with the final approval of Jan Brewer, who was governor at the time.

Even with changes and adjustments to the projects, the vast majority of bond projects have been completed. County financial documents show 98 percent of the 1997 general obligation bonds have been spent, as have more than 96 percent of the 2004 bond funds.

Another common claim is that the voters approve a certain level of spending on one thing, but the county either spends too freely or spends it on a project voters never intended. However, such criticism is often based more in rumor than in fact.

For the new county courts complex, for example, critics like to point out that $76 million in 2004 bond funds was allocated, but the final price tag was more than $130 million. However, the 2004 bond ordinance says total project costs were estimated at $91 million, with additional funds planned from the city and other sources. It was to be a joint city and county courts facility, but the city backed out of the deal, adding to county costs.

The biggest added expense came from an unexpected historical and archaeological remediation required by the discovery of a cemetery on the site that was used from the 1860s to 1880s. The city decommissioned it in the 1880s and told families to remove loved ones’ remains, but some simply removed the headstones.