Tim Steller is the Star’s metro columnist. A 20-plus year veteran of reporting and editing, he digs into issues and stories that matter in the Tucson area, reports the results and tells you his opinion on it all.

Something historic is stirring in Tucson politics.

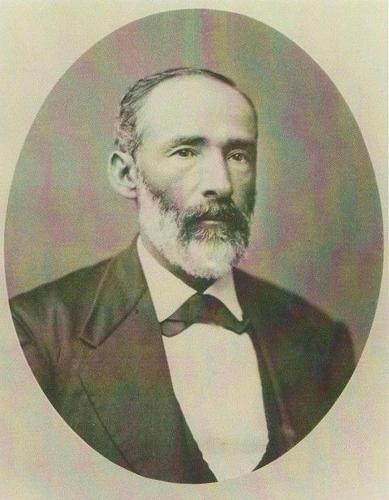

You can tell because people are talking about Estevan Ochoa — and he died in 1888.

Ochoa, a prominent Tucson businessman in his time and the founder of the local public schools, was the city’s last Mexican-American mayor, elected in 1875. That’s a shocking fact, especially when you consider that white Anglos weren’t the majority of the local population until after 1900.

Regina Romero mentioned Ochoa’s name Tuesday night as she did interviews in Spanish and English after her win in the Democratic primary election for mayor. She’ll face independent candidate Ed Ackerley in the general election.

“The last time we saw a Mexican-American mayor in the city of Tucson was 1875,” Romero said. “So we have the possibility of, besides electing the first woman mayor, electing the second Mexican-American mayor in the city of Tucson in 150 years.”

Now, if Romero is elected in November, these facts aren’t going to pave the roads, hire more police or expand job opportunities. But as Romero hugged supporter after supporter during her election night party, sweating in the jam-packed humanity of the American Eat Co., it was plain to see that something more was happening than just a primary election victory.

Romero represents a historic change that is surprisingly late in arriving to Tucson. I mean, how is it possible that Tucson has never had a female mayor when Arizona has had four female governors — so many that it’s no longer even a big deal?

In an interview at her office Wednesday, Romero downplayed the significance somewhat, reverting to the cake metaphor that she likes to use.

“This is what I usually tell people,” she said. “Those facts are just frosting on the cake. The cake is my experience, my qualifications, the vision, the issues that I care about and I stand for. That’s the cake. The frosting is the fact that we’ve never elected a woman mayor in the city of Tucson.”

Ackerley will probably have a hard time fighting Tucson’s long-delayed march toward making this history. But if he does succeed, it will likely be in good measure by criticizing Romero as insufficiently friendly to business and as a cog in the political “machine” of U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva.

This machine metaphor struck me Tuesday night as the happy crowd beamed with their success. People talk about a political “machine” as if it’s unfairly established to rig elections, and that may be the case in some American places and some times. But the way the machine worked this time was to organize an army of volunteers and to inspire allies in outside organizations to go out, knock on doors, make calls and send mailers.

The friendships with outside groups like Chispa AZ, Planned Parenthood and Mi Familia Vota were useful to Romero’s campaign — they spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on outside efforts to benefit her run, turning her into a favorite in the race.

As the party wound down, Grijalva told me that’s what it has taken for Mexican-Americans to regain political power in Southern Arizona — organizing, making alliances, walking, working like a machine.

And while it’s mostly beneficial, he noted, candidates allied with him — candidates like Romero and Ward 1 Democratic primary winner Lane Santa Cruz — also are targeted because of their association. It’s a two-edged sword, though the machine-honed edge is probably sharper.

For her part, Romero bristled when I asked her Wednesday to respond to the criticism commonly heard outside that machine that she would be Grijalva’s “puppet” if elected.

“I think that’s terribly chauvinistic. I think that’s not giving me credit for the brains and experience that I have,” she said. “To say that I’ll be a puppet and he’ll pull the strings is not knowing who I am.”

It also perpetuates a history that has gone on shockingly long in Tucson.

After the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in 1880, the city really began to evolve out of its Mexican past, University of Arizona professor of anthropology Thomas Sheridan told me in an email Wednesday.

“Before the railroad, the Mexican community absorbed the relatively few Anglo immigrants, who married into Mexican families and formed partnerships with Mexican entrepreneurs,” he said in the email. “After the railroad, that bicultural, bilingual accommodation began to break down.”

Anglo-American men moved in and began to dominate Tucson business, using their access to Eastern capital to lever themselves to the top of local power, said Sheridan, author of “Los Tucsonenses: The Mexican Community in Tucson, 1854–1941.”

People like Estevan Ochoa, who made his money in the freighting business, moved to the margins.

Now, though, the people in those margins are moving back to the center of Tucson’s story.