Whether Arizona gets to keep its ban on ballot collection or “harvesting” could depend on whether a former legislator who first proposed the law was trying to suppress minority votes, and how his motive affected his colleagues.

During a two-hour hearing Tuesday, U.S. Supreme Court justices were told that it was then-Sen. Don Shooter who first attempted in 2011 to make it a crime for anyone to collect another person’s voted ballot and take it to polling places.

Mom and baby javelina: Wait until you see the little cutie

That came a year after Shooter, a Yuma Republican, had won his 2010 election with 53% of the vote — receiving 83% of the non-minority vote but only 20% of the Hispanic vote. Shooter alleged that some votes that went to his Democratic foe may have been fraudulent, but presented no proof.

It took five more years for lawmakers to pass the ballot harvesting law. But when it was challenged, Judge William Fletcher of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals cited the early effort and concluded Shooter was “in part motivated by a desire to eliminate what had become an effective Democratic GOTV (Get Out the Vote) strategy.”

And Fletcher said nothing really changed between 2011 and 2016.

“Republican legislators were motivated by the unfounded and often far-fetched allegations of ballot collection fraud made by former Sen. Shooter,” the judge wrote.

Republican Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, defending the statute before the U.S. high court, told the justices that’s irrelevant.

“You cannot impugn motive to one legislator to a group of 90 independent, co-equal actors spread across two houses in the Legislature,” he said.

Brnovich said the law is a legitimate effort by lawmakers to minimize the possibility of fraud or coercion when political groups go door-to-door and seek to collect someone’s ballot.

He also said nothing inherent in the law decreases the opportunity for minorities to vote, which he said is the test under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, regardless of whether there is some evidence that minority voters are more likely to depend on someone else to take their early ballots to the polls.

But his arguments were not helped by Michael Carvin, who is representing the Arizona Republican Party, which was granted the right to intervene to help defend the 2016 law. He was asked by Justice Amy Coney Barrett why the Republican Party is involved in the case and opposed to ballot harvesting.

“Because it puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats,” he acknowledged.

“Politics is a zero-sum game,” Carvin continued. “And every extra vote they get through unlawful interpretations of Section 2 hurts us. It’s the difference between winning an election 50 to 49 and losing an election.”

That goes to another finding by the 9th Circuit last year in voiding the law. Fletcher said the record shows that before 2016, minorities were more likely than non-minorities to get someone else to turn in their ballots. By contrast, Fletcher wrote, “the Republican Party has not significantly engaged in ballot collection as a get-out-the-vote strategy.”

There are some indications that the conservative justices may defer to the decision of Arizona lawmakers in enacting the 2016 law. But there are facts that complicate the issue.

One is that there was no actual evidence of fraud cited by Arizona lawmakers in enacting the law. In fact, statutes already on the books made it a crime to refuse to turn in someone else’s ballot.

But then-Rep. J.D. Mesnard, R-Chandler, argued that is irrelevant.

“What is indisputable is that many people believe it’s happening,” he told colleagues during floor debate. “And I think that matters.”

And Brnovich cited the 2005 recommendations of the Commission on Federal Elections Reform, co-chaired by former President Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, that said states should prohibit outsiders from handling absentee ballots of others.

Anyway, Brnovich told the justices, it’s not like this law — and the other challenged one that says ballots cast in the wrong precinct are not counted — significantly impact the ability of minorities to vote.

He acknowledged there are “slight statistical differences” in how both laws affect minorities. But Brnovich said the court needs to look at the totality of the circumstances.

“No one was denied the opportunity,” he said.

He said the state provides many ways of voting, including early voting and at voting centers ahead of Election Day. And the state has a “no excuse absentee balloting” provision, meaning that anyone can ask for an early ballot by mail.

“So there are a whole plethora of options in ways for people to exercise their right to the franchise,” Brnovich said.

Chief Justice John Roberts specifically asked attorney Jessica Ring Amunson why that report by the commission that Carter co-chaired does not provide enough reason for lawmakers to ban ballot harvesting. She represents Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, who has taken the position that both the ban on ballot harvesting and the prohibition on counting votes cast in the wrong precinct violate federal law.

“States can have an interest in securing their elections through limiting ballot collections,” Amunson responded. “But when you look at the particular fact here, that does not appear to have been Arizona’s interest.”

Bruce Spiva, attorney for the Democratic National Committee, which filed the original suit, underlined the point, saying there’s nothing in the legislative record to suggest lawmakers were persuaded by anything in that commission report. He emphasized that legislators also had no evidence of voter fraud before enacting the 2016 law.

Amunson said there is something the court does need to consider.

“What we have is a record that shows that Native Americans and Latinos in Arizona rely disproportionately on ballot collection and white voters do not,” she said. And that, Amunson said, comes back to Shooter.

“The entire purpose of introducing the law by Sen. Shooter was to keep Hispanics in his district from voting and was premised on far-fetched racially tinged allegations that Latinos in the district were engaging in fraud with respect to ballot collection,” Amunson said.

Shooter, who later was elected to the state House, is no longer a legislator. He was expelled by his colleagues in 2018 for violating policies against sexual harassment.

Amunson also told the justices they should take note the admission by Carvin about the political nature of this legal fight.

“Candidates and parties should be trying to win over voters on the basis of their ideas, not trying to remove voters from the electorate by imposing unjustified and discriminatory burdens,” she said.

There was some indication the justices could end up with a split decision on the two issues.

On one hand, they noted, the 2016 law changed long-standing practices allowing ballot harvesting. That might be considered an affirmative violation of the Voting Rights Act.

By contrast, they noted the policy of counting only the votes cast at the right precinct dates to 1970. Brnovich argued that is necessary to properly administer the voting system.

He also said the extent of the impact of that law is minimal, saying that in the 2016 election there were only 3,970 ballots that were rejected because they were cast in the wrong precinct out of more than 2.6 million votes cast by all methods, including early and day-of voting.

But Amunson said the important thing for the justices to consider is the evidence that minority voters were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected because of being in the wrong precinct than white voters.

A ruling may not occur until June.

Photos: Saguaro National Park through the years

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument cactus garden in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument West visitors center, left, with two rangers' apartments under construction in 1966.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East unit loop drive in 1958.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East, ca 1950s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument in 1935.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow at Saguaro National Park East (then called Saguaro National Monument) on Dec. 23, 1965.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Undated photo (probably 1950s) of tourists enjoying picnics and hiking at Saguaro National Monument.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument visitors center ca 1940s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Home Shantz, a plant scientist and president of the University of Arizona in the 1920s, was instrumental in establishing Saguaro National Monument in 1933.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panorama of cactus forest in Saguaro National Monument, 1931.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

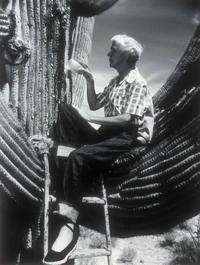

Dr. Alice Boyle applies Penicillin to a Saguaro cactus at Saguaro National Monument. Dr. Boyle’s studies of saguaros included treatments with penicillin that were somewhat successful. Later research showed that the loss of old saguaros was a result of age and periodic freezes, not a “blight”!

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Freeman family in Saguaro National Monument in 1936.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Freeman's adobe home in Saguaro National Monument in 1934.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A park ranger with visitors on the loop drive in Saguaro National Monument in 1961.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Centennial Saguaro cactus outside the Saguaro National Monument visitors center.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument cactus

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow storm in Saguaro National Monument in 1937.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill at the Tucson Mountain Range in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking east from Saguaro National Park, along Picture Rocks Road in the Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016. In the distance, cloud rise over the Santa Catalina Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro carcass framed at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A southerly view out the window of a picnic shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s that was built with surrounding rock in the Ez-Kim-In-Zin Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A desert tortoise makes its way down Kinney Rd. in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro cactus off Golden Gate Rd. holds a top full of flower buds at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill towards Wasson and Amole Peaks from left in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors take a look at trail maps on the patio of the Red Hill Visitor Center at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors from Denver stroll one of the many trails off Golden Gate Rd. at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panoramic view from Spud Rock, including the city of Tucson, from six images, ranging from southeast at left to northeast at right, near Mica Mountain on the western slopes of the Rincon Mountains in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A hawk watches from his perch at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) perches on a rock near the Signal Hill Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panther and Safford Peaks in the Tucson Mountains North of Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses the sharp edge of a stem of a Saguaro fruit to slice the husk to get to the sweet meat inside as she harvests the fruit in the Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses a kuipaD to harvest saguaro fruit in the Saguaro National Park 2005. During the early summer Tucker camps out in the park to harvest and cook the fruit just as her Tohono O'odham ancestors did. Tucker died in 2019 at age 71.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Bob Martens uses a kuipaD, lengths of Saguaro ribs topped by a small limb of creosote, to knock down ripe Saguaro cactus fruit as he helps Stella Tucker during the Tohono O'Odham harvest at Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Under the early morning sun, Jerry Yellowhair strengthens the joint where a small creosote branch is attached to a length of Saguaro rib to make a kuipaD, used to reach the Saguaro fruit.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

1907: Prominent Tucsonan Levi Manning and his family spent the summer at a get-away log cabin high in the Rincon Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park East, in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Some of the pots, pans and iron skillets used by the staff during their stays at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers, left, and wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey look over the camps visitors log shortly after arriving at Manning Camp 8,000 feet above sea level in the Saguaro National Park, on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Horse shoes on one of the logs making a wall in the cabin at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers splits wood for the evening's fire at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The view east over Reef Rock, lower left, from Rincon Mountains near Manning Camp in Saguaro National Park, June 2, 2016

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey, left, and next generation ranger Ryan Summers prepare to do some upgrades to the facilites at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sid Kahla, left, and Thor Peterson get a pannier balanced on Goose while packing seven mules for a resupply of Manning Camp ranger station in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wasson and Amole Peaks at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Monsoon clouds gather over the cactus forest in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro cacti backlit by western sun at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A horizontal sliver of sun catches a stretch of cactus in front of the Rincon Mountains just off the Mica View Trail in Saguaro National Park East, Friday, August 12, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

This old stone building was constructed in the 1930's by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the Cam-Boh Picnic Area at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

In the aftermath of an evening summer storm, lightning arcs through the night skies over the Saguaro National Park West in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Harris' antelope squirrel, a year-round resident of the Sonoran Desert, comes out of from under a bush for a look-see near the Golden Gate Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A jack rabbit munches on some greens near the Broadway Trial Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hikers in Saguaro National Park, like these on the King Canyon Trail in the park's unit west of Tucson, can pay park entrance fees at trailheads using a smartphone.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Loop of connected trails at Saguaro National Park East, made up Shantz, Pink Hill, Loma Verde, Cholla and Cactus Forest trails in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

From atop an outcropping under the Rincon Mountains, Next Generation Ranger Ryan Summers points out the ancient fault line that shifted and formed the Tucson valley to a group of visitors during a geology tour of Saguaro National Park East on April 26, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaros stand on a ridge line as massive storm clouds drift in the distance along the Hohokam Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis gets the strap as tight as possible with the help of trail supervisor Nick Huck while preparing a 70+pound propane tank for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park, Rincon District on April 14, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park ─ Sunset can be a colorful time along a network of trails near the eastern end of Broadway.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Ranger Donna Gill points out cactus flowers and birds during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hedgehog cacti are in brilliant fuchsia bloom at many sites around Tucson from Sabino Canyon to Tucson Mountain Park and Saguaro National Park in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Russell Jones takes a picture at the Saguaro National Park West Red Hills Visitor Center in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Poppies were blooming profusely at Saguaro National Park West on February 23, 2015

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Mike Ward of Saguaro National Park, left, and volunteer LaDeana Jeane observe a Saguaro cactus while conducting a census at the east section of Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gavin Youngstrum drives a roller along the bed of the new Mica Springs Trail, work which will make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Power tools and motorized equipment is used very rarely in the park. The trail is not in a wilderness area so the prohibition on the use of power tools and machinery doesn't apply.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A blue Arizona lupine mixed in with a handful of yellow bladderpod along the Ringtail Trail in Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Park Ranger Ann Gonzalez watches the campers in her group as they go over a map during Junior Ranger Wilderness Day Camp at the Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Petroglyphs are among the many wonders at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Runners top the first climb as the sun rises at 6:30am, during the annual 8K Saguaro National Park Labor Day Run at Saguaro National Park East in 2007.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A saguaro under the stars, including a smudge of the Milky Way, at the Broadway Trail Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sunset reflected in a mud puddle left over from heavy rains a few days earlier at the Broadway Trail Head of the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The moon hangs high over Wasson Peak as Ranger Donna Gill leads hikers during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Volunteers help yank out the nonnative, invasive buffelgrass at Saguaro National Park East.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Using a laser, amateur astronomer Joe Statkevicus points out a few interesting objects in the night sky to Landon George and Vickie Miller at a Saguaro National Park East Star Party in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A bee works through a patch of baldderpod in the Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District along the Ringtail Trail in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Trail worker Brad Duffe redistributes material as he and his trail crew lay down a bed for a new surface, part of remodeling the Mica Springs Trail to make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Riders maneuver their mounts down a hillside just north of the Douglas Spring Trail in the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District, Friday Nov. 27, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Tim and Connie Phillips, from Salt Lake City, look for photo angles during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016. The retired couple sold their home and are "following the weather" across the country in their RV.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A few items, photos and brief entries in tiny notebooks from an unofficial shrine at Mica Mountain in Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The sun sets over the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District on Oct. 8, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Scarlett Gates and the rest of the tour group watch the last few minutes of daylight from a rock outcropping along the Tanque Verde Ridge Trail during their guided sunset hike in Saguaro National Park East on April 16, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gold poppies stand out against a backdrop of cacti and blue desert sky at Saguaro National Park west of Tucson on March 11, 2019.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Rainbows pop up over Saguaro National Park East, as the first major monsoon storm of the season begins to roll into the valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 11, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A half rainbow arcs over Saguaro National Park East as a highly localized cell of monsoon rain sweeps through a small band of the eastern valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 28, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A light coating of snow remains on the Rincon Mountains seen nearby the Broadway Trailhead in Saguaro National Park in Tucson, Ariz. on January 27, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A cactus in the Saguaro National Park East stands in front f the snow in the higher reaches of the Santa Catalinas, Tucson, Ariz., March 13, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A lighting strikes hits in the Saguaro National Park, east of Tucson, Ariz., July 29, 2021, one of several storm cells that skirted the city.