Like many of Tucson’s hardy pioneers of the 1800s, Fritz Contzen put a living together through many adventurous occupations — his included Texas Ranger, military express messenger, international boundary commissioner and discoverer of mines.

Frederick “Fritz” Contzen was born to Philipp and Augusta (Steinmetz) Contzen at Stormbruch, in the principality of Waldeck, German Confederation (now Germany), on Feb. 27, 1831.

His father was the chief forester on the estate of the Prince of Waldeck for many years and shared this knowledge of forestry with his eldest son Julius. As a result, in the mid-to-late 1840s, Julius was offered a job in Texas as a forester.

Before his older brother left for the U.S., young Fritz, still in his teens, begged him to take him along to this new land. The two brothers joined up with other men including many former army officers sailing to Galveston, Texas.

The voyage was both exciting and scary for Fritz Contzen, as the crew and passengers battled a fire on board the sailing vessel, then battled each other over disagreements, and lastly watched their provisions run dangerously low before arriving after almost four months at sea.

Contzen was looking for adventure, so in 1850 he joined the Texas Rangers with William A. A. “Bigfoot” Wallace as his captain and Peter R. Brady (namesake of Brady Avenue in Tucson and Brady Peak in the Grand Canyon) a lieutenant; Brady later moved to Tucson and became Pima County sheriff.

As a Ranger, Contzen fought the Comanche Indians around San Antonio and also enforced the laws of the state.

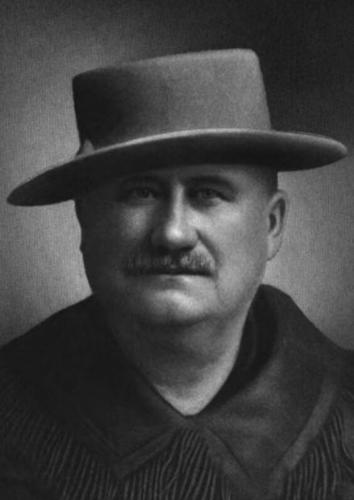

Fritz Contzen

He first gazed upon the land then being called the Gadsden Purchase — present-day Southern Arizona and southwest New Mexico — in 1854 as a member of Major W.H. Emory’s U.S. Boundary Commission. The commission was set up to mark the border between the United States and Mexico after the Gadsden Purchase of 1853 added almost 30,000 square miles to the U.S.

In the meantime, Julius had made the acquaintance of a fellow German immigrant named Herman Ehrenberg (namesake of Ehrenberg, Arizona on the Colorado River). Through his influence, Julius set up a ranch at Punta de Agua in the Santa Cruz Valley, about three miles south of San Xavier Mission near Tucson. Contzen joined him after his work was done with the boundary commission.

In 1856, the two Contzen brothers, traveling on horseback trailed by pack animals along with two Papago (O’odham) Indian guides, headed south to Sonora, Mexico to stock up on supplies. Near Imuris, Sonora, they were attacked by about 35 Apache warriors with firearms. They endured a barrage of bullets, leaving Contzen with a broken leg and Julius with 18 wounds, and likely would have perished if not for a group of Imuris citizens who came to their rescue.

The following year Julius died, likely from the wounds received in the Apache attack. Contzen stayed at the ranch and began supplying the new Butterfield Overland Mail line with horses and feed he obtained from the Papagos (Tohono O’odham).

On Aug. 20, 1861 in Tucson, Contzen wed Mariana Ferrer, whose Spanish ancestors were pioneers on the west coast of Mexico for generations. She soon died, however. The next year, on Jan. 9th, he again married, this time to Margarita Ferrer, likely a sister or cousin of his first wife. Two sons would be born to the couple. One died young and Philip, also known as Felipe, survived.

In 1862, the U.S. was engulfed in the Civil War and Union soldiers had pushed Confederate cavalry out of Tucson. Union Col. J. H. Carleton ordered several Tucsonans to be examined before a board of officers to see if they were Confederate sympathizers. Contzen was among them, possibly because he had come from Texas. As a result, Contzen and others were sent as political prisoners, under the suspicion of sympathy for the South, to be confined at Fort Yuma. About a month later, after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States, he was released and returned to Tucson.

On May 8, 1864, Contzen joined other prominent citizens such as Charlie Meyer (namesake of Meyer Avenue), John B. “Pie” Allen (namesake of the Pie Allen Neighborhood), Hiram Stevens and M.B. Duffield (namesakes of the Stevens-Duffield House), and Hill de Armitt at a municipal convention in Tucson. The attendees established a temporary municipal government which consisted of a mayor and five councilmen.

Three days later, John N. Goodwin, governor of the Arizona Territory, proclaimed the municipality of Tucson and appointed William S. Oury as mayor and Mark Aldrich, Juan Elias, Hiram Stevens, Francisco S. Leon and Jeremiah Riordan as councilmen. This government doesn’t appear to have lasted more than a year, but it made Oury the first mayor of Tucson — although by proclamation instead of election — after formation of the Arizona Territory.

Contzen was also part of a movement, three years later, which involved signing a petition to have the 1867 or fourth territorial legislative session held in Tucson since the first three had been in Prescott. This petition was also signed by early pioneers including Mike Mckenna (namesake of the old McKenna Street), Charles Shibell (namesake of Shibell Street in Tucson and Mount Shibell in Santa Cruz County), and Samuel Hughes (namesake of Tucson’s Sam Hughes Neighborhood). Instead of just a legislative session being held in the Old Pueblo, the whole capital of the Arizona Territory was moved here from 1867-77.

By 1864, Contzen was serving in the role of a military express messenger riding alone in the dark from Tucson to Blue Water Station near the Gila River to deliver post orders that were then taken by military escort to the Prescott area. This was a particularly dangerous job and many expressmen were killed by Apache who roamed the area.

The fear of Apache attacks was always on the minds of early pioneers like Contzen, every time they left the safety of a town like Tucson or Tubac or one of a small number of military forts in the Arizona Territory.

He likely heard the news the following year of two men, William Wrightson and Gilbert W. Hopkins, involved with mining in the Santa Rita Mountains, who were killed about a mile from Fort Buchanan. Mount Wrightson and Mount Hopkins in the Santa Ritas were later named in their honor. Hopkins Street, which is believed to have existed from around 1865 to about 1870 and was originally called Calle de la Alegria and now is Congress Street, might have been named in honor of Gilbert W. Hopkins.

In 1870, Contzen’s occupation in the U.S. Census was listed as a U.S. mail contractor, as a sub-contractor for Louis Zeckendorf, co-owner of A & L Zeckendorf wholesale and retail dealers. He or one of his employees brought mail from Tucson to Prescott, Tucson to Tubac and Tucson to Sasabe, facing the same dangers from Indians. He lost some of his employees in this way.

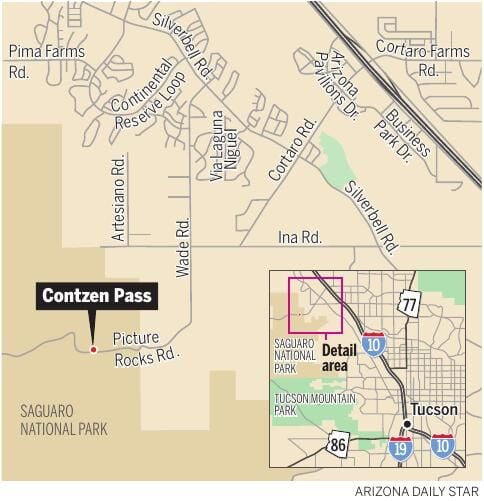

It was likely during the time he was a military express messenger in the mid-to-late 1860s or a U.S. mail contractor in the early 1870s, on his trips to the Gila River, possibly looking for a shorter route or a route to avoid Apaches, that Contzen came across a pass in the northern part of the Tucson Mountains, which now bears the name Contzen Pass. Or, he might have found it during the same period, on a mining exploration trip looking for a shorter route to the Silver Bell Mountains, in which he discovered what became known as the Young America mine.

In the early 1870s he also discovered what became the San Xavier mine near the San Xavier Mission.

In 1873, desiring his son Philip get a good education that wasn’t available in Tucson, Contzen and his wife sailed to his homeland in the principality of Waldeck, in what was then called the German Empire. While overseas, Contzen’s wife and son learned several languages and enjoyed the benefits of his family’s high station in that society. The family remained there for about seven years before returning home.

On this trip Contzen likely learned of his little brother Heinrich’s success as a professor and noted lecturer on economics at a number of universities in Germany and Switzerland. Heinrich had also founded several newspapers and written several books, mainly on the national economy, among them Grundbau der Nationalökonomie or The Basic Structure of the National Economy.

In the 1881 Tucson City Directory, Contzen is listed as a capitalist residing on Meyer Street (now Meyer Avenue) between Congress Street and Cushing Street. His capital investment may have included the Prince Bismarck mine in the Amole District (part of the Tucson Mountains), believed to have been co-owned by pioneer James Lee (not the namesake of Lee Street).

A few years later Contzen ran afoul of the law for illegally smuggling cattle into the United States and was sentenced to 24 hours in a county jail.

When Contzen died at his home in Tucson on May 2, 1909, a reporter for The Tucson Citizen newspaper, then located at 30 Belknap Street (now part of Scott Avenue), wrote a short article entitled “The Pioneers,” which read:

“The passing of Fritz Contzen draws attention to the thinning ranks of our pioneers. Many are gone but not forgotten. And to those remaining, Arizona cannot do too much honor. Arizona owes everything to its pioneers. Through the dangerous wilderness they blazed the trail on which we of a later generation walk and gather flowers. But (not) for these old men Arizona would still be of the wilderness. They bought us our heritage with their blood and bone. Their story is part of the heart treasure of every Arizonan.”

Located at Treat Avenue and Waverly Street, the park is open to the public. Video by Gabriela Rico / Arizona Daily Star.