Spanish missions served as early outposts of European civilization in both Mexico and what is now Southern Arizona. They were first operated by the Jesuit Order of the Roman Catholic Church serving as missionaries and educators to the Native population.

The purpose of these missions was to aid in the colonization and exploration of land to the financial benefit of the Spanish Empire while converting the native population to Catholicism. Several notable missions including Tumacácori, Calabasas and Guevavi made a significant impact in the early history of what is now Santa Cruz County. These villages included adobe mission churches and residences.

Tumacácori, the Pima word meaning curved peak, was originally established as a vista wherein priests would visit and located on the Santa Cruz River 48 miles south of Tucson and 12 miles north of the Mexican border. Established by Jesuit Father Eusebio Francisco Kino in 1691 and was the first mission established in the boundaries of what later became Arizona.

Christened Mission San Cayetano de Tumacácori its original presence was on the east side of the Santa Cruz River until the Pima Revolt of 1751 necessitated its relocation to its present location on the west side of the river when it was renamed San José de Tumacácori.

The year 1767 marked the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Spanish Empire by decree of King Carlos III of Spain who was concerned about their growing power and influence over the Church. In 1773, the Franciscan Order took over and Tumacácori became a cabecera or main mission hosting priests until the last padres departed in 1841. The two story bell tower was never completed due to lack of funds and labor. The ruins became a national monument on Sept. 15, 1908, as a measure to deter its destruction from treasure seekers and in 1990 became a national historic park. Limestone quarried from the Santa Rita Mountains 25 miles north of Tumacácori was used to cover the exterior of the church in the form of white limestone plaster.

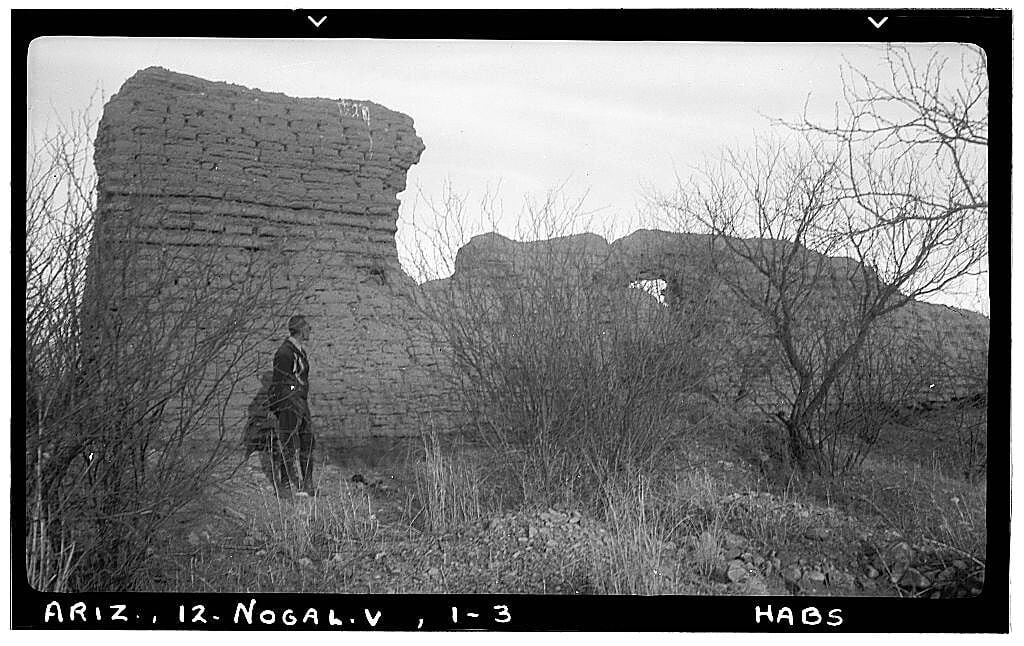

An onsite lime kiln at Tumacácori Mission used to burn limestone for building material.

The southwestern foothills of the southern Santa Rita Mountains hosted mines producing low and high grade lead and silver ores worked by Jesuit missionary padres in the 17th century.

The Spanish government actively encouraged mining granting military protection to local mining ventures. Many of these exploited the labor of the local Indian tribes affiliated with the local O’odham Indians, which included the Papagos, Pimas and Sobaipuri.

Spanish miners were required by the Royal Crown to pay the quinto also known as the royal fifth of the gross bullion output. It is certain that there were miners who were not forthcoming in their production figures to avoid paying this fee. Mines were operated in semi-secrecy to the benefit of the mine operator and it is probable that the profit was pocketed and hid as bullion or plate in undisclosed places wherein many of the lost treasure tales originated passed down through generations.

On the southwest slope of the Santa Rita Mountains in 1909, a view of the Salero Mine a historic silver deposit first worked by the Jesuits in the 17th century.

In what became known as the Tyndall Mining district, hosted some of the earliest recorded mining efforts in the American West. Jesuit missionaries affiliated with Tumacácori discovered and worked the Alto, Montosa, Salero and Wandering Jew mining properties dating back to 1688. The Salero Mine, Salero translated in Spanish meaning “salt cellar” or “salt mine” is said to have supplied both salt and silver to the local missions.

The Jesuit miners were limited by the technology of the day which included use of rough iron bars used to drill to depths of several feet or more into lime filled rocks broken further by hammers with ores packed out by the miners carrying rawhide buckets and relying on crude ladders comprised of poles with notches cut out. The lead and silver ores was smelted by adobe reverberatory furnaces and separated by cupellation as a means of removing the impurities from the gold and silver by melting the impure metal in a cupel, a flat porous high temperature resistant dish. The metal then received a blast of hot air from a furnace lined with porous materials including marl and bone ash removing impurities including copper and tin through oxidation and vaporization.

Other methods for extracting gold and silver singular in rock involved milling with mercury using arrastras and then retorting the amalgam or mixture. The Spanish also sought out placers using gravity separation techniques involving hand picking, water separation and air winnowing, a dry separation technique of gold from sand along water courses and washes where gold had naturally eroded from gangue rock.

Exterior façade of the Tumacácori Mission.

After the culmination of the Spanish Rule in Arizona in 1821, rumors of buried mineral wealth abound in the region with silver lodes discovered on both sides of the Santa Rita Mountains. Americans arrived after the Mexican War of 1848 discovering the remnants of mining operations in the form of slag east of the Tumacácori Mission. Other examples include:

According to Papago Indian tradition bullion was removed from the Virgin Guadalupe Mine three miles southwest of the mission and relocated to a nearby mine tunnel. The mine was worked from 1508 to 1648. It was seized by Coronado in 1540. The mine is said to contain 2,050 mule loads of silver and 905 loads of gold.

The Bells of Old Guevavi Mission near Calabasas were cast of heavy black silver-copper ore mined from the San Cayetano Mountains 20 miles north of Nogales. Padres are said to have sealed the mine and buried the bells at an undisclosed location. Guevavi was abandoned in 1775 due to Apache attacks and its remote location from the Spanish military garrison at Tubac.

The Planchas de Plata “slabs of silver” strike at Arizonac in 1736, a mile south of the present international border between the U.S. and Mexico included silver slabs weighing up to several thousand pounds. It is possible that some of this silver cache may remain hidden by the Spanish miners to avoid paying the royal fifth to the Crown.

No doubt some of the Spanish mining investment remains to be discovered and unearthed which will continue to allure present and future treasure seekers as it did in 1854, when Arizona pioneers Charles D. Poston and Herman Ehrenberg journeyed from San Francisco by boat to the Gulf of California through Alamos, Sonora, and on to Tubac to inspect old mines and missions between Tucson and Mexico.

Alto Mine, camp and mill with tunnel at outcrop below summit, circa 1909.

Map depicting locations of historic Arizona and Mexico Missions.

Another angle of Tumacácori Mission from the Convento Fragment.

Historic Tumacácori Mission Cemetery.

Mining cupels as seen on table