Ida Redbird dug the clay she needed for the creation of her pots from the banks of the Gila River. Some say she tasted the gritty sand, and if it was too salty, she discarded it and moved to another location seeking the right consistency of soil she demanded for her work.

Once she was satisfied she had found the correct material, she might spend an entire day sifting the rocky substance to ensure no small stones embedded in the dirt would ruin her pottery.

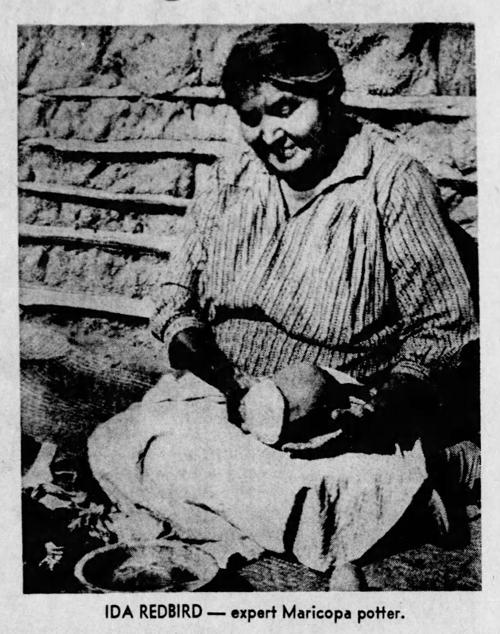

Ida used a “chupamat,” a large, heavy stone to pound her clay. Adding water, she kneaded the clay to remove any air bubbles and flattened the clay before using a curved paddle to push up the walls of the pot. A small stone or wooden anvil held against the inner wall of the container thinned out the sides as she paddled the outer surface to form the shape she desired.

Sometimes she rolled out a coil of clay and adhered it to the pot’s rim to finish the shape.

Once she was satisfied with the vessel, Ida used red slip (clay pulverized into powder and mixed with water to form a thick, soupy texture) to rub the vessel inside and out. She polished the dried slip with a smooth stone before adding another layer of slip and a coat of shortening or lard over the outside of the pot. She cleaned the pot once again and set in the sun to dry while she prepared a bed of mesquite coals.

After placing the pot on the hot coals, Ida took mesquite bark sap and boiled it to a gummy consistency. Once the pot had cooled, she applied another coat of red slip, picked up a toothpick-sized stick fashioned from a desert shrub and began drawing with the cooked and cooled gooey sap, recreating geometric designs that might date back to the ancient Hohokam people. Or she might create a drawing of her own choosing.

The decorated pot was put back on the coals for one last firing before it was ready to be sold. For all this labor, if she was lucky, Ida might receive 25¢ or 50¢ for an exquisite work of art.

Maricopa potter Ida Redbird was born March 15, 1892, in Laveen, Arizona, on the Gila River Indian Reservation. She attended Phoenix Indian School and served as an interpreter for anthropologist Leslie Spier while he was writing his book, Yuman Tribes of the Gila River, in the 1920s.

But it was her work in revitalizing Maricopa pottery that brought Ida public recognition. She was considered a master potter and was credited with the resurgence of ancient Maricopa pottery techniques.

During the Depression years, Maricopa pottery sold for pennies. Ida and other potters could not afford to travel to larger cities and sell their products for such a minimal sum. Ida tried desperately to promote her own work as well as that of other Maricopa potters. She worked tirelessly to raise the prices on these works of art that took days to produce.

It was a difficult sell until around 1937 when museums and other supporters took up the cause and established the Maricopa Pottery Association with the idea of creating a market for the artistry of the Maricopas and have it sell for justifiable prices. For her outspoken stand and efforts to value Maricopa pottery, Ida was elected the first president of the association.

Ida enjoyed discussing the process of pottery making although she seldom gave herself credit for her own work, consistently lauding other potters in the association. Her expertise in her craft eventually led to a teaching position at Phoenix’s Heard Museum. She remained affiliated with the museum for over 30 years.

Unfortunately, the Maricopa Pottery Association did not last as long as did Ida’s stint with the Heard Museum. The approximately 17 women potters who made up the association were encouraged in their work, but the women had to travel to Phoenix to sell their merchandise, leaving their families to cope on their own. The onset of World War II also impeded sales. The association only lasted a few years.

Ida had married Charley Redbird and as the years passed, many of their children and grandchildren lived with them on the reservation. Charley died in 1945, and Ida continued to support her extended family despite suffering from diabetes, arthritis and failing eyesight.

In 1970, a reporter noted that Ida’s property, which consisted of 20 acres, much of which Ida leased to local farmers, was comprised of a “yard around her two-room adobe home of mud and ocotillo spines ... dotted with chickens, a lean-to shower stall, a water faucet (the only one on the property), the gifts of a refrigerator and a TV set that always were worthless in a household without electricity and gas, and of course, that ever-present tub and washboard.”

On Aug. 10, 1971, the temperature in Phoenix hovered around 100 degrees as 79-year-old Ida finished her wash in the old tub and began working on her pottery. No breeze broke the unrelenting heat as she safely nestled her pots on the hot mesquite coal bed. She stopped to rest for a moment under a tamarisk tree that had shielded her from the blistering sun for many years.

The old tree had probably seen a few more years than Ida and at that moment, one of its branches snapped, falling on the resting woman, and killed her. Prophetically, she had once told her brother, “I might just end my life under that tree.”

Ida Redbird was “one of the very best of the Southwestern Indian potters and worthy of her title as the master potter of the Maricopas,” according to Tom Cain, then curator of the Heard Museum. Arizona State University established a scholarship in her name, and many of her unique pots can still be viewed at the Heard.

RELATED:

For Star subscribers: Travel party endured several attacks as they crossed Arizona to Fort Yuma.

Helped raised money to restore the town's stately courthouse, other landmarks.

She was successful in passing the bill to have the song “Arizona” adopted as the state anthem.