Of all the asteroids in all the orbits throughout the solar system, how did the University of Arizona choose Bennu to visit and sample?

It was part process of elimination and part luck, said Carl Hergenrother, who identified the target of the UA-led NASA mission to visit an asteroid and gather up a couple ounces or more of its rock.

Hergenrother was hired in 2004 by the OSIRIS-REx mission to find a good candidate to sample.

The team had already decided where not to look.

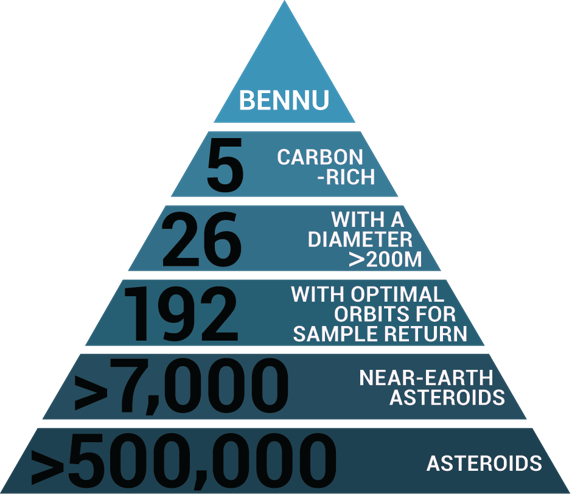

Our solar system has approximately 500,000 asteroids, but most are in the main Asteroid Belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Only 7,000 or so have orbits that bring them close enough to our planet to be classified as “near-Earth.”

Most had orbits that would require an extra large rocket to reach or were too small for the purposes of this mission. They spin rapidly and would present too much of a moving target.

There was also a concern that 4.5 billion years of spinning would have cleansed the surface of regolith — the geologists’ term for loose surface material from rocks to dust.

“Only 26 fit the bill, and only five of them were suspected of being carbon-rich,” Hergenrother said.

That was important. “These carbon-rich, or carbonaceous, asteroids may represent the kind of asteroid that seeded the earth with water and organics,” he said.

If you’re going to spend $1 billion to bring a scoopful of pebbles back to Earth, they should be interesting ones, with maybe some organic compounds, amino acids, precursors of life — that kind of thing.

Hergenrother had already chosen a tentative candidate by September 2005 when he decided to observe an asteroid known by its discovery number — 1999 RQ36 — from the UA’s 61-inch telescope just beneath Mount Bigelow in the Santa Catalina Mountains northeast of Tucson. It had come back into view.

Observing through colored filters, he determined that it was bluish-black and probably carbonaceous.

Then he discovered that he wasn’t the only one to have observed the asteroid in detail. Astronomers Ellen Howell and Mike Nolan, now part of the OSIRIS-REx team, had seen it soon after its discovery in 1999, using the giant radio telescope at Arecibo in Puerto Rico.

It had also been observed in radio frequencies by NASA’s Goldstone Array in California.

The radio astronomers had determined the asteroid’s shape and size. It was big enough and it did not appear to have a lot of boulders that would block collection of surface regolith.

Hergenrother sent an instant email to the mission leaders, the late Mike Drake and current principal investigator Dante Lauretta.

I said, ‘Look, there’s data, it just hasn’t been published.’ Within two days we had decided this is our target.”

POTENTIALLY DANGEROUS

Bennu is observable from Earth every six years. When it came around again in 2011, Hergenrother was put in charge of an observation campaign that used some of the world’s highest-resolution telescopes, in addition to NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes.

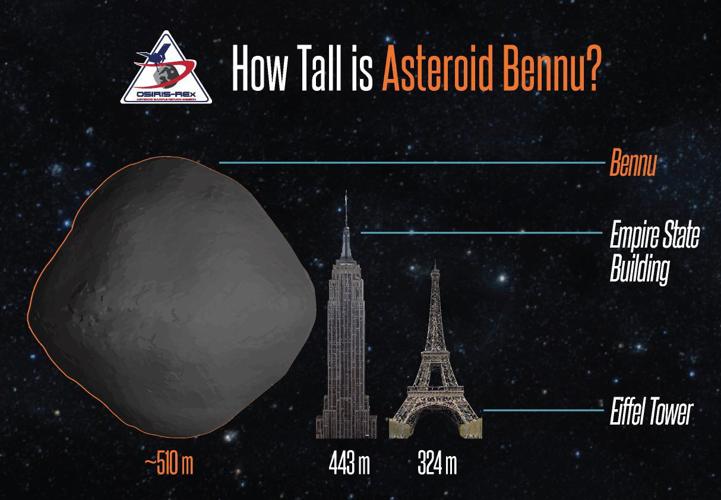

The asteroid is the most studied in the solar system, said Hergenrother, with the exception of asteroids that have actually been visited by spacecraft. Pole-to-pole, Bennu is taller than the Empire State Building and about 500 meters in diameter at its equator.

It orbits the sun every 1.2 years, traveling at 63,000 mph and rotating every 4.3 hours.

It approaches Earth every six years, coming perilously close beginning in 2175, with a 1-in-2,700 chance of striking Earth in the next two centuries, NASA’s Near Earth Object Program says.

Bennu was not selected because of its potential danger, said Ed Beshore, the mission’s deputy principal investigator.

Beshore said limiting the choices to asteroids in near-Earth orbits made it inevitable that a potentially dangerous asteroid would be the target.

Information gathered in the three years OSIRIS-REx closely observes the asteroid will let scientists better understand its orbit and the subtle forces of heating and cooling that influence its path over time, Beshore said.

That will enable scientists to better predict an asteroid’s path and provide information that will help to deflect one from a collision course with Earth, he said.

That knowledge, says Dante Lauretta, OSIRIS-REx principal investigator, will be the mission’s “gift to the future.”