This is part 1 in a three-part series. Click the below links to read parts 2 and 3.

In the dusty front yard of her home of three years, Rosemarie Navarro put her hands over her sightless eyes, shouts mounting around her. The constable had finally arrived to enforce an eviction order she believed to be illegal.

It was just after 4 p.m. on a steamy Friday in late August. Rosemarie and her long-time partner Gabriel Chavez had held out hope they could fight the eviction, after getting notice their landlord was taking them to court. Then, after the judge in Pima County Consolidated Justice Court quickly ruled in their landlord’s favor, they’d started packing.

Rosemarie, 41, and Gabriel, 46, knew an eviction likely meant losing their Section 8 rent assistance, which they’d secured after three years on the waiting list. They feared an eviction on their record would make it harder for them to find a decent landlord willing to rent to them.

But mostly, they were outraged that they were being evicted for nonpayment of rent, when Section 8 had already paid the bulk of their $587 August rent and said they’d tried repeatedly to pay the remaining $152. The landlord wouldn’t take it, they said.

Blind due to the effects of diabetes and an unsuccessful eye surgery last year, Rosemarie felt powerless as she listened to Gabriel arguing with the constable, pleading for more time to move. Her furniture, clothes and memories were stacked haphazardly around her under a pop-up tent.

“You have 20 minutes,” Constable Oscar Vasquez told Gabriel, handing over the pink writ of restitution that allowed him to change the locks on the duplex at the base of “A” Mountain. “Get the essentials you need, man.”

Gabriel, Rosemarie and her 20-year-old son Mario had been up all night packing, yet they still seemed to be in disbelief about what was happening.

“We had the money to pay up,” Gabriel told the constable, his voice rising. “We can’t force her to take it!”

“Gabriel, please,” Rosemarie said through tears. “You’re making it worse.”

Long-time friends had shown up and, with increasing urgency, they began shuttling boxes and furniture into their vehicles.

“It’s the judge’s decision,” the constable said. “I’m just enforcing it.”

Constable Oscar Vasquez explains to Gabriel Chavez that he and his longtime partner, Rosemarie Navarro, have 20 minutes to leave the home they have rented for three years. On Aug. 24, Vasquez was enforcing an eviction ordered by the Justice Court the week before.

"BOMB GOING OFF"

For low-income families living on the edge, an eviction can upend the precarious balance that kept them afloat and push many into homelessness, said Bonnie Bazata, program manager for Pima County’s Ending Poverty Now program.

“It’s like a bomb going off,” she said.

Over the last fiscal year, judges in Pima County Consolidated Justice Court ordered an average of 25 evictions each day, an Arizona Daily Star analysis found. The stakes are high for families with no savings and no safety net. After an eviction, renters often struggle to come up with a security deposit and first month’s rent for a new home. Personal belongings are lost or cast aside if the family can’t afford a storage unit. Pets are abandoned or taken to the pound.

The court includes monetary judgments with the eviction judgment, ordering tenants to pay rent owed, plus hundreds of dollars in late fees, court fees and attorneys’ fees. Debts are sent to collection agencies, and wages are garnished. Many bounce between motels or friends’ couches as they search for a new home, draining their limited resources. Parents can lose their jobs in the chaos, and children are sometimes forced to change schools.

Housing instability has a psychological impact, too. Low-income urban moms who had been evicted in the previous year were about twice as likely to report multiple symptoms of depression compared to those who weren’t evicted, according to a 2015 Harvard University and Rice University study.

And evicted families who receive housing assistance almost always lose their federal Housing Choice Vouchers, known as Section 8. Participants pay 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities, and the program covers the rest.

In Tucson today, nearly 16,000 families are on a waiting list for the cash-strapped program, which distributes an average of $524 in monthly rent assistance for participants. The waiting list has been closed to new applicants since January 2017.

Tucson’s Section 8 program has just 5,654 vouchers, an allocation based on a HUD needs assessment completed in the 1990s.

“We’re currently serving people who applied in 2015,” said Sally Stang, director of Tucson’s Department of Housing and Community Development.

BETWEEN THE EXTREMES

This isn’t a story of exploitative landlords unlawfully evicting decent tenants, although legal aid attorneys can attest that it happens regularly. Many landlords are patient and compassionate, giving struggling tenants plenty of chances to catch up on overdue rent. Some tenants are manipulative and dishonest, engaged in criminal activity or destructive to their landlord’s property.

The bulk of cases fall between the extremes. Often, renters simply fall behind after the unexpected happens: a job loss or reduced work hours, a car repair or hospitalization. Previously patient landlords may decide they can’t afford to keep accepting partial rent payments and have to finally prioritize their own bills.

For a large subset of renters, it doesn’t even take a major life event to fall behind in rent. To be considered affordable, housing costs should make up no more than 30 percent of a household’s monthly income. But the majority of low-income renter families in the U.S. spend more than half of their income on housing, Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond reports.

Among poor renter households in Tucson earning between 50 percent and 100 percent of the federal poverty level, 92.5 percent spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, according to a 2018 survey by UA student researchers.

“Those numbers are shockingly high,” said Brian Mayer, associate professor of sociology at the UA. The 250-household survey was part of Mayer’s semester-long field workshop on poverty in Tucson, which aims to study the living conditions of hundreds of families, ranging from extremely low income to middle class, over five years.

In Arizona, a worker earning the state minimum wage of $10.50 would have to work 56 hours a week to afford a modest one-bedroom rental home, according to a 2018 report from the National Low-Income Housing Coalition. Nationally, the statistics are more dire: A worker earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 would have to work 2.5 full-time jobs to be able to afford a one-bedroom.

The fundamental problem underlying what many are calling an eviction epidemic in the U.S. is the lack of affordable, decent housing, combined with stagnant wages and widening income inequality, advocates say.

“Eviction is a symptom. The problem is poverty,” said Matthew R.K. Waterman, managing attorney for Southern Arizona Legal Aid, which provides free legal counsel in civil cases for qualified low-income clients.

The situation is ripe for exploitation. Unscrupulous landlords understand the enormous leverage they wield over desperate tenants — especially those with past evictions or criminal records, or those who rely on Section 8. They may use the threat of eviction to deter tenants from objecting to degraded living conditions, or to pressure a tenant to leave before the lease term is up. Some file an eviction in retaliation for a tenant demanding needed repairs.

Legal advocates say busy justice court judges sometimes fail to discern between lawful and unlawful evictions, and the system is structured to give landlords the benefit of the doubt from the outset. Facing off against a property owner, usually represented by an attorney specializing in housing law, tenants are unprepared for the legal battle to prove their case, and rarely can afford their own attorney, housing attorneys say.

“It’s not about justice,” Waterman said. “It’s about following the legal rules and unfortunately, those rules are stacked strongly against poor people.”

Not only are evictions a symptom of poverty, they’re one of the leading causes of it, said Marcos Ysmael, program manager at the Pima County Housing Center.

“It’s one of the triggers that can spiral a person or a family into a cycle of poverty,” he said. “It can be so hard to recover.”

Local advocates are pushing for more resources for struggling renters, more affordable housing development, as well as better education for landlords and tenants alike about their rights and responsibilities. The Arizona Department of Housing has proposed committing $2 million to a pilot program to help prevent evictions, mainly through increased funding to agencies that provide emergency rent and utility assistance, and in streamlining referrals to legal aid attorneys who represent tenants.

During a recent public forum on the pilot program, a representative of the Arizona Multihousing Association said the group was excited about a proposed increase in resources for eviction prevention. Member landlords often have real friendships with their tenants, said Lauren Romero, Tucson area executive for AMA.

“The last thing our landlords want to do is evict their residents,” she said.

Some attendees, including Cesar Aguirre of Tucson, chafed at the rosy picture painted by property owners at the forum.

“I know there’s probably a lot of landlords that really do care about their tenants, but the majority of the people I deal with on a daily basis have the opposite experience,” said Aguirre, who at the time was living and working as a community organizer at Casa Maria soup kitchen. “They have landlords that are slumlords that live in California and other places, that impose higher rents than they should in certain areas, don’t fix things, push tenants out if they complain about things. We see a lot of that on a daily basis.”

CHANGING THE LOCKS

Landlord Nancy Ramirez and her daughter Tracy quietly watched from inside a blue truck as their tenants, Rosemarie and Gabriel, were evicted. The Ramirezes own almost two dozen Section 8 units in Tucson.

After phone calls went unreturned, a reporter approached the Ramirezes on two occasions: during the Aug. 24 constable eviction, and a couple weeks later when Rosemarie and her family went back to gather the remainder of their belongings as the property owners observed. (Until recently, evicted renters had up to 21 days to retrieve their possessions after the locks are changed. This year, the state Legislature reduced it to 14 days.) Tracy Ramirez declined to respond to Rosemarie’s claim that she refused to accept August rent.

“I said no comment,” she said when asked to comment for this story. “Get off my property or I’m calling the police. This is harassment.”

Three police officers had arrived with Constable Vasquez to keep the peace as the locks were changed. Police backup came at the request of the landlord, who feared a confrontation, Vasquez said.

Tucson Police Department records show no calls for service during the couple’s tenancy, other than a welfare check when Rosemarie couldn’t find her brother last year.

“You can’t judge people because of the way we look. This guy works hard,” said Malena Pacho, who has known Gabriel for 15 years and came over to help with the move. “I want to cry. This really sucks, because they’re good people.”

HOUSING CRASH

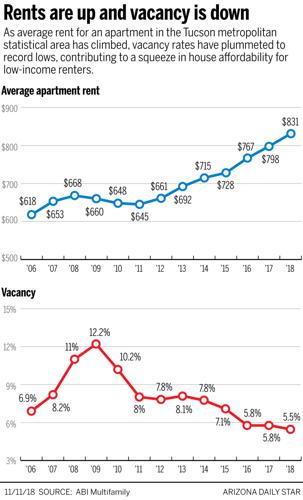

Eviction filings in Pima County Consolidated Justice Court peaked at more than 17,000 in 2006, when low vacancy rates meant landlords could be more selective in choosing their tenants.

Evictions may have also spiked because renters had few alternative housing options when they fell behind in rent, said Ginny Huffman, owner of Imagine Realty Services in Tucson, which specializes in property management.

“Instead of just packing up and leaving (before the landlord filed an eviction), they actually were sheltering in place,” said Huffman, who is also board president of the Tucson Association of Realtors. “They would wait until the landlord had to be pushed to do an eviction.”

After the housing crash, when vacancy rates rose and landlords were more willing to work with struggling renters, evictions in Pima County dropped steadily for years.

In the just-ended fiscal year, 12,909 eviction actions were filed in Pima County Consolidated Justice Court.

But housing advocates are now bracing for an increase in housing instability, as rents are rising and vacancy rates have dropped to historic lows in Tucson.

“Right now we’re seeing a change in the market,” said Stang, the city housing director. “As the market tightens, landlords have less patience and are more quick to move to evictions than they were in a really soft market, when they were more willing to work with someone because it might have been more challenging to fill a unit.”

Tucson was one of the last cities to recover from the Great Recession and housing crash, so the fallout from a hot rental market is just emerging, said Peggy Hutchison, CEO of the Primavera Foundation in Tucson. The nonprofit works to alleviate poverty and prevent homelessness.

Federal housing funding for local programs is falling: A decade ago, government funding made up 70 percent of Primavera’s operational budget but is now down to about 50 percent, with donations and other revenue making up the rest, she said.

Matching low-income clients with affordable units is harder now, Hutchison said. Recently one of Primavera’s family resource specialists in its Family Pathways shelter program had to make hundreds of calls before she found housing for 30 families, she said.

“It’s really a tragedy,” she said. “There’s just a huge gap in finding affordable housing.”

Even tenants with housing have reported feeling pushed out as out-of-state landlords, seeing relatively low rents here, buy up “underperforming assets,” make improvements and raise the rent, housing advocates said.

“We’ve heard from constituents that they feel like their landlords are trying to drive them out by improving the property, and raising rents as they do so, which does unfortunately happen in markets that are on the upswing,” said Ysmael of the Pima County Housing Center.

INVOLUNTARY DISPLACEMENT

Eviction statistics understate the extent of involuntary displacement, which can be caused by a prohibitive rent hike or new property owners deciding not to renew existing leases. The mere threat of eviction can cause a tenant, fearing the consequences of a formal eviction, to move out before legal action starts.

Housing instability pushes people into their cars, the streets, desert washes or overburdened homeless shelters, decimating social cohesion and draining community resources, housing advocates say.

Local agencies with emergency rental and utility assistance funding cannot meet the demand. Emergency funds allocated for the entire month are distributed to struggling renters almost immediately.

“Sometimes, it’s a matter of days,” said Interfaith Community Services CEO Daniel Stoltzfus. Last year, Interfaith spent $1 million in direct assistance to people in crisis, and 93 percent of that was for people trying to avoid eviction, Stoltzfus said. On a peak day, the agency will get thousands of calls seeking financial assistance before the monthly funding runs out, he said.

“Some of that is just people hitting redial, but still,” he said, “It’s heartbreaking.”

Among the growing population of seniors in Tucson, the housing crisis is particularly acute.

This year, the Pima Council on Aging got a surge in calls from older adults in crisis. In June, the agency got 64 urgent requests for emergency assistance to avoid eviction, homelessness or utility shut-off, compared with eight in January, when the agency started tracking the data.

“Things certainly appear to be getting worse,” said agency director W. Mark Clark.

The Administration of Resources and Choices, which provides crisis services for seniors, has seen a 400 percent increase in crisis calls compared with last year, most of them related to housing instability or imminent eviction. Some of that is due to the expansion of outreach efforts, but the need is clearly growing, staff said.

“The situation has worsened very much over the past year,” said Debbie Chandler, executive director of the nonprofit. “It’s a huge problem, and it’s not a problem that nonprofits can necessarily solve. This is a community issue, and it’s going to have to be addressed at a higher level by creating housing. HUD needs to funnel some dollars into all of our communities to provide affordable housing for seniors that is livable.”

Rosemarie Navarro clutches her Chihuahua as her brother Rene and partner Gabriel Chavez move furniture out of their rental home before they are evicted. They said they repeatedly tried to pay the remainder of the month’s rent but the landlord would not take it; the landlord wouldn’t comment to the Star. Evicted Aug. 24, they stayed in a friend’s guesthouse for months.

CHANGING NEIGHBORHOODS

Even after she lost her vision last year, Rosemarie could maneuver comfortably through her Menlo Park home at the base of “A” Mountain. But in a friend’s unfamiliar guesthouse, where she and her family are staying after being evicted, she feels lost. Blindness has minimized her, she said.

“Before, I used to be real talkative,” she said. “My whole world changed. It’s hard to be like this.”

Rosemarie and Gabriel grew up nearby, in Barrio Hollywood. They met in elementary school and have been together for 18 years, with Gabriel helping to raise Rosemarie’s son Mario.

Over five years, the couple had two rented homes in Menlo Park from the Ramirezes. Little by little, they saw the neighborhood changing with more wealthy, white families moving in. Nearby, a new home at 941 W. Grandview Lane is listed at $345,000, and a renovated home at 947 W. Nearmont Drive is going for $329,000. The nearby landfill is being transformed into a $50 million Caterpillar headquarters for about 650 employees.

Gabriel is convinced his landlord wanted her old Section 8 tenants out so she could raise the rent, and take advantage of the newfound desirability of their community.

In July, Rosemarie and Gabriel had already agreed to leave by Aug. 31 after Ramirez gave them a 30-day notice to vacate, which stated she did not intend to renew their lease.

Yet when the couple tried to pay their final month’s rent at the start of August, Ramirez had refused it without explanation, they said. She filed an eviction action for nonpayment of rent, prompting the couple to devote their energy to fighting the eviction rather than preparing for the move.

Rosemarie, who was the leaseholder, showed up to her Aug. 17 justice court hearing hopeful the judge would see there was no need for an eviction: She had repeatedly tried to pay everything she owed. Even with $105 in court fees now added on, she was willing to pay that, too. The family just needed until the end of the month to pack and find a new home.

Listen to Rosemarie’s full eviction hearing

During the hearing Judge Pro Tem Cecilia Monroe, who declined to comment on the case, seemed to dismiss Rosemarie’s comments, according to a recording of the hearing.

“I have the money,” Rosemarie began when it was her turn to speak.

“At this point, they don’t have to accept your money because they have given you already a 30-day notice to vacate,” the judge said.

This is inaccurate, because the notice to vacate, dated July 28, guaranteed Rosemarie’s lease was good through Aug. 31, said housing attorney Sabrina Fladness, who was not involved with the case. If Ramirez refused to accept August rent, she was the one in violation of the lease agreement, Fladness said.

In six minutes, of which Rosemarie spoke for about 30 seconds, the case was heard and decided.

The next fight would be to try to save their Section 8 voucher, which was terminated by the eviction.

Newly remodeled houses at the foot of “A” Mountain sit behind a fence with “How much is rent now” spray-painted on it. Some new and renovated homes in the Menlo Park area are listed for more than $300,000, contributing to concerns among long-term residents about increasing rents and lack of affordability. Rents are rising throughout Tucson.

HOUSING SHORTAGE

Nationally, there is a shortage of more than 7.2 million rental homes that are both affordable and available for extremely low-income renter households, according to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition.

In Tucson, 60,000 more affordable housing units are needed to meet the demand, said Stang, Tucson’s housing director. Meanwhile, the number of landlords participating in the Section 8 program is dwindling, she said.

Today, a county-run website listing units that accept Section 8 vouchers has 566 listings, compared with more than 900 a year and a half ago, Stang said.

Housing officials say a national housing crisis would have been exacerbated by the Trump administration’s proposed cuts to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, which the National Low-Income Housing Coalition said would have meant 200,000 families losing their rental assistance. Both chambers of Congress rejected the cuts proposed in the fiscal year 2019 budget, which should be finalized next month, but federal housing funding for many programs remains below 2010 levels.

Inadequate funding to help struggling renters will inevitably result in greater costs in managing homelessness down the line, not to mention the collateral damage to families thrown into chaos along the way, Stang said.

“I see it just backfiring,” she said.

The Trump administration also proposed adding work requirements for housing assistance, but that would only waste scarce resources on administrative work, while adding little benefit, Stang said.

The vast majority of extremely low-income renters are elderly, disabled or already in the work force. In Tucson, 70 percent of Section 8 participants are elderly or disabled. Of the remaining 30 percent, nine in 10 are working, Stang said.

Primavera has received calls from teachers seeking emergency rental assistance, Hutchison said.

“We have these stereotypes that (poor) people aren’t working,” she said. “They’re already working, and they’re not able to get by.”

The good news is, in the last five years, the city changed some policies to help developers apply for the competitive federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program. Since 2014, 542 affordable units have been built or are under construction through the tax-credit program, Stang said.

“We have more affordable housing being built in the last four years than the last 12 years before that,” Stang said.

Tucson is experiencing a surge in economic growth, with companies like Caterpillar, Amazon and Geico bringing thousands of new jobs to town. But a wave of workers relocating here to take those jobs will contribute to the fierce competition for existing affordable housing, Hutchison said.

ONE MISTAKE

In the early 20th century, eviction was a rare event that triggered protests and rent strikes, said sociologist and Princeton professor Desmond in his 2015 book, “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.”

Today, the loss of one’s home is largely accepted as commonplace. Many see the fall-out from missed or late rent payments as a cut-and-dried contract violation.

Roger Putzi rents properties to 15 families in Tucson and has been a landlord for nearly 50 years. For Putzi, evictions are rare: The last eviction he filed was about eight years ago, he said.

“It’s very simple,” he said. “Just be a good person and pay your rent. That’s really all it takes.”

But for those living paycheck to paycheck, one mistake can cascade into disaster.

Curtis Ramon, 35, and Rafaela Lopez, 26, started dating last year when she was working on the Tohono O’odham Nation as a receptionist in a child welfare office in Sells, the capital of the Nation. Curtis came around with his mother, selling homemade traditional sweet breads. In January, the couple moved in together at Summit Ridge Apartments in Tucson.

“I wish we hadn’t went there to begin with,” Rafaela said. “It took a big toll on us.”

Rafaela Lopez and a nephew, Roman, moved into her mother’s guesthouse after Lopez’s online rent payment in May took longer than expected to process. She was evicted June 25.

Soon after the move, Rafaela’s sister lost custody of her 2-month-old son Roman. With no one else in the family to take him in, Rafaela agreed to foster her nephew. Curtis became the full-time caregiver for the baby while Rafaela commuted to the reservation each day for work. Curtis knew his tattoos and imposing stature could put people off, so he made a point to stop by the property manager’s office and chat, or discuss repairs he hoped to make to the apartment.

“I try not to be intimidating, but people see me as intimidating,” he said. “So I always have a smile on.”

Getting the rent paid on time was often stressful because of the timing of Rafaela’s paycheck, but she’d always gotten it done, hurrying to cash her check and get a money order to Summit Ridge before late fees kicked in.

Then, in May, Rafaela tried an online application for paying rent, called AppRent, at the recommendation of Summit Ridge. On May 4, Rafaela deposited her paycheck and then paid her rent through the app. She got an email confirmation, which Curtis shared with the Star, stating her payment had been accepted. Rafaela didn’t realize the money hadn’t yet cleared her bank account. Perhaps because they paid on a Friday, the rent wasn’t processed until four days later.

At the time, “she was under the impression that we paid, so we paid other bills,” Curtis said.

“We needed stuff for the house, diapers, clothes,” Rafaela said. “When we got (Roman) into our custody, he only came with three pairs of clothes.”

Rafaela’s bank account statements show the payment processed on Tuesday, May 8. By then, her account had insufficient funds.

The couple scrambled to get emergency assistance from Rafaela’s home district on the reservation, the Schuk Toak District, to cover what they owed. The district approved about $800 and mailed a check.

But the funds from Rafaela’s district were held up by Chase Bank, which locked Rafaela’s account for suspicious activity, Curtis said. The district later told Rafaela the check had been returned and they could not send another one.

Meanwhile, Summit Ridge told the couple they now also owed $200 in attorneys’ fees, since the property manager had filed an eviction.

Summit Ridge attorney Judy Drickey-Prohow said the eviction came down to a simple case of nonpayment of rent.

“All we know is that the payment bounced, we didn’t get the money,” she said. “We notified her, she didn’t come up with the money before the court date. If she’d come up with the money, plus attorneys’ fees and court costs and late fees, she wouldn’t have been evicted.”

When Rafaela and Curtis showed up at their eviction hearing on June 6, they requested a trial to fight the eviction.

During a June interview, Curtis said he was intent on showing they made every effort to pay rent. Unable to find a lawyer to help, Curtis planned the defense himself, collecting bank documents and filing a subpoena for a representative from Chase Bank to appear.

“I’m going to protect my family. I’m going to fight this eviction,” he said during a mid-June interview, rocking a sleeping Roman in his baby carrier.

Curtis Ramon says he tried to fight what he called an unfair eviction in June. The resulting stress eventually led to the end of his relationship with girlfriend Rafaela Lopez, he said.

On the morning of the June 25 hearing, the Chase Bank representative arrived in court. But Curtis’ ride to court had fallen through at the last minute, when Rafaela was already halfway to her job on the reservation. Despite his frantic texting, Curtis couldn’t get a ride.

Back in justice court, the case was over in under a minute with a judgement in favor of Summit Ridge. But even if Curtis had made it, his arguments wouldn’t have changed the fact that Summit Ridge did not receive the May rent.

Curtis and Rafaela say their relationship fell apart under the stress of the eviction. Rafaela and now 9-month-old Roman moved into a studio guest house in the backyard of her mom’s rented home.

On a warm September night, Rafaela bounced Roman on her legs as he smiled into her phone during a video call with Curtis, who had moved back to Sells. After they hung up, she cried for their lost relationship and the uncertainty of her future. She’s now four months pregnant with Curtis’ baby.

“I don’t want to go through this alone,” she said.

Her mother plans to move back to Sells at the end of the year, but moving back to the reservation is not an option for Rafaela.

“I want to give my nephew the best life possible, but I just don’t think it’s going to happen on the reservation,” she said.

She’s looking for a job in Tucson, while still commuting two hours a day to work in Sells. But with an eviction now on her record, she worries more about finding a home than a new job.

Gabriel Chavez, who earns his living doing bicycle and car repair or home improvement jobs, had to give up his work to become a full-time caregiver for his partner, Rosemarie Navarro. Navarro lost her vision due to diabetes and a failed eye surgery last year. The couple said they were unlawfully evicted after the landlord refused to accept their rent payment.

FIGHT FOR SECTION 8

Gabriel can make $700 or $800 a week rustling up bike and car repair work, or home improvement jobs. But for months, his primary role has been Rosemarie’s caregiver. Their only income since she lost her vision has been the disability benefits she recently secured.

After they were evicted, the couple could only afford to pay a friend a couple hundred dollars to stay in her guesthouse until they could find a new place to rent. The house didn’t have gas, but cold showers were fine in the summer. But by October, it was getting colder. Tensions were rising with the friend who was housing them. The couple’s Ford Taurus broke down, and Rosemarie was growing more and more depressed.

The couple had to appeal their Section 8 termination before they could begin their housing search in earnest. During their Oct. 3 appeal hearing, Rosemarie tearfully told the judge that she’d tried to pay everything she owed to the landlord, including on the day of the eviction, but the landlord wouldn’t take it.

Listen to brief excerpts from Rosemarie’s Section 8 appeal hearing

“I have no control over that,” said Judge Frederick Klein, according to a recording of the 28-minute hearing.

“We know, but you have control over this,” Gabriel said.

Gabriel was certain they’d lost their appeal, but ultimately Klein ruled he would overturn the Section 8 termination, since Rosemarie had been willing to pay. “Client’s tender should have been accepted and the eviction should have been dismissed,” he wrote in his hearing report.

It was a rare win. Section 8 investigator Mary Irbinskas, who represents the city in these informal hearings, said in the four years she’s been doing this, she can only recall one other reversal.

Despite the good news, Rosemarie and Gabriel’s stress and desperation were mounting. They started looking for a new place to rent, calling 25 places over the course of a week. They couldn’t find one that would accept Section 8. The friend who was letting them stay in her guesthouse disconnected the electricity, and told them to move out before the start of the next week.

Again, they started packing.

“I don’t even know what we’re going to do,” Gabriel said a few days before they were supposed to be out. For the time being, he was focused on finding a dry place to store their belongings, since the forecast was calling for rain that weekend.

As for permanent housing, he said, “I’ll stress about it on Sunday.”

Josie Agnew, who is the primary breadwinner for her family of four, gets ready for her job as a waitress/bartender at Texas Roadhouse. In trying to avoid an eviction on her record, Agnew said she ended up in a worse situation, with a $7,000 debt sent to a collections agency. She and her family have been living in motels since May.

CHAOS AFTER EVICTIONS

The chaotic fallout after an eviction or involuntary move can be almost as damaging as the eviction itself. Many families end up in motels, bouncing between friends’ couches or on the streets.

Getting ready for a mid-September evening shift at Texas Roadhouse, Josie Agnew, 31, carefully applied makeup and glued on delicate eyelashes in the south-side Studio 6 motel room that housed Josie, her brother José, 28, their two disabled parents and their dog. A tattoo on her forearm reads: Trust Your Struggle.

The room was tidy, as 95 percent of the family’s belongings had been in storage since May, at a cost of $100 a month. The family spent more than $4,000 at motels as Josie searched for a new place to rent.

Josie was the family’s primary breadwinner, while her brother cared for their parents. Josie wasn’t taking any days off, and her manager had been giving her extra Texas Roadhouse shifts to help her out.

The family wasn’t technically evicted: Josie had agreed to a deal with the Starrview at Starr Pass property manager that she thought would be the best way to avoid that stain on her record. But she says what she agreed to got her into a worse situation.

Neighbors at Starrview had been complaining about her disabled stepdad for a while. In January, Josie had received a notice that his behavior was disturbing the neighbors and constituted a material breach of the lease. One more notice and they would be evicted.

Josie’s stepfather, David Akers, has bipolar disorder, has had multiple strokes and has a heart condition. His medication often made him act “loopy” and forget things, she said. He took walks and talked to all the neighbors, picked up cigarette butts, and asked neighbors to use the phone. He ate all the cookies in the community room and talked too much to the staff there.

Josie brought in extra bags of cookies and figured they were in OK standing: In April, she signed a new 13-month lease.

The next month, she was a few days late on rent, but she was prepared to pay $1,200 plus late fees. But when she tried to pay, property manager Astrid Gamez-Linhart said she’d received more complaints about her stepfather and couldn’t accept her payment and was planning to file an eviction, Josie recalled.

Josie said she started crying and said, “I can’t have an eviction on my record.”

The property manager said she’d cancel the eviction if the family moved out voluntarily. Josie could keep her May rent, so that she’d have money to find a new place to live, and the property manager would send the amount owed to a collection agency, Josie recalled.

Josie agreed, but quickly, as she started searching for a new place, she realized she’d made a mistake. Every potential apartment she called rejected her, citing the debt that had been sent to collections.

“The whole plan was to avoid an eviction,” she said. “I feel like this is worse than an eviction. I should have gone with my gut, I should have asked for legal advice.”

Attorney Drickey-Prohow, who represented Starrview and corresponded with Josie for weeks, said the property manager (who declined to comment) was trying to help the family as much as possible. She denied the property manager would have advised Josie not to pay her rent. The deal was, as long as Josie and her family turned in their keys before June 2, they agreed to not file the eviction based on her stepfather’s behavior. But Josie was still supposed to pay May’s rent.

“Management was trying to give her an option so she wouldn’t have an eviction,” she said. “From what I can see, they were trying to do her a favor.”

Because Josie didn’t pay May’s rent, the manager filed an eviction action on May 16 based on nonpayment, Drickey-Prohow said. The property manager told Josie she’d vacate that eviction as long as she turned in the keys before June 2, which Josie did.

Josie believes the property manager didn’t want to file an eviction based on her stepfather’s behavior, because it would have been too hard to prove his behavior violated the lease — particularly since they’d just signed a new 13-month lease.

José Agnew irons his sister Josie’s shirt as his stepdad, David Akers, makes tea at a motel. They have spent more than $4,000 at motels since being forced to relocate in May.

Housing attorney James Daube, who represents tenants but was not involved with Josie’s case, said fair-housing rules can apply if an accusation of material noncompliance is based on a tenant’s mental health. Tenants in this situation should seek legal counsel to determine if their landlord must overlook erratic behaviors as part of the “reasonable accommodation” for disabilities required by the federal Fair Housing Act.

“You can’t ask people (other residents) to tolerate threats or violence,” he said. “But loud noises occasionally, or strange behavior that people might otherwise consider bothersome” would be protected under the fair-housing law.

On a fall afternoon, Josie finished up her makeup and sat down at a small desk in the motel room to make a call. She took notes as she talked to her liaison at the collection agency. She was trying to get an answer as to why the $2,600 debt she thought she owed to Starrview had snowballed into more than $7,000. She put her phone on speaker and took notes while her brother José cooked Top Ramen noodles for their mom on the stovetop.

“My sister is the glue that makes us all stick together,” he said as he stirred. “She’s the rock for us.”

Josie learned the biggest charge was a $3,700 early termination fee, for breaking the 13-month lease she signed in April.

“I’m not going to pay $3,700 for a lease I didn’t break, Travis,” she told the man on the phone. “I never wanted to leave.”

Travis said he would mark the account “in dispute.”

Tenant attorney Daube said when two parties agree to end a lease early, landlords can still insist upon the remedies under the lease agreement, such as an early termination fee, even if the tenant is leaving at the landlord’s insistence. To avoid the fee, Josie needed to get it in writing that the landlord was waiving the fee.

In October, José, who had been caring full-time for their parents while Josie worked, got a full-time job as a cashier at the Shell station near the motel. Josie has started working fewer shifts, so either she or José can be home with her parents. She hopes they’ll soon have saved enough to move out of the motel.

“I am tired,” she said. “I don’t even care where we go at this point.”

FINDING HOME

On a Sunday in early November, the sunset threw pink light across the backyard of the Menlo Park guesthouse where Rosemarie, Gabriel and Mario had now been staying for two months.

They were supposed to move out on a rainy weekend in mid-October, but their friend who owns the place gave them a reprieve, letting them stay through the end of the month, Gabriel said. He was starting to think the friend didn’t believe they were still waiting on Section 8 to approve a new voucher and then do an inspection of the two-bedroom apartment he found.

“I don’t blame her,” he said. “I don’t understand why it’s taking so long. We didn’t think we’d be here this long without electricity.”

Gabriel was able to repair a generator that can at least power some lights, at a cost of $10 or $15 a day in gas. But without cooking appliances or a refrigerator, they can’t make decent meals at home or store perishables, so they eat out more than they can afford, he said. They’re losing assets.

“I’ve sold tools. I’ve sold things I shouldn’t have sold,” he said.

They’ve paid the friend about $600 for their stay, but now she needs to rent the place out, he said. Gabriel was prepared for her to come home at any moment and tell them to leave. If that happens, Gabriel said he plans to get a tent and camp his family in a friend’s backyard. He knows it’s not a good solution.

Without a car, they’re limited in motel options. It’s important that they stay close to Barrio Hollywood and Menlo Park, where at least they have a community of friends who can offer rides and support. The weekly places they called are either too expensive or won’t take their dogs, Gabriel said.

“For the first time in my life, I’m stumped,” he said. “I just don’t know what to do. If it was me by myself, no problem, I’d just go live in the streets. I don’t want them to go through that.”

In the fading light, Gabriel squatted beside a blue, two-seat bicycle he’d been fixing up, since their car is still out of commission. He took Rosemarie on a bike ride through the neighborhood the day before, hoping to give her an escape from the increasingly chilly and dark guesthouse.

Inside, Rosemarie was lying down and wasn’t up for talking to anyone. She said she can’t get warm and in the dim light, she can’t even make out shapes in front of her, so she can hardly move around without help, Gabriel said. The anxiety and sense of imprisonment are taking a toll on their relationship.

Gabriel was planning to go back to Section 8 for a status update the next morning. Just as it’s been for the last three months, his family’s well-being feels like it’s out of his hands.

“We went through some rough times, but nothing like this,” he said. “Putting that eviction on us threw everything in a spiral. All over $152. And we had the money.”