It took 13 years after the industrial solvent trichloroethylene was found in south-side Tucson groundwater in 1981 to get a city treatment plant online to start cleaning it up.

It took 11 years after the solvent 1,4-dioxane was found in the same groundwater in 2002 to get a treatment plant online to start cleaning it up.

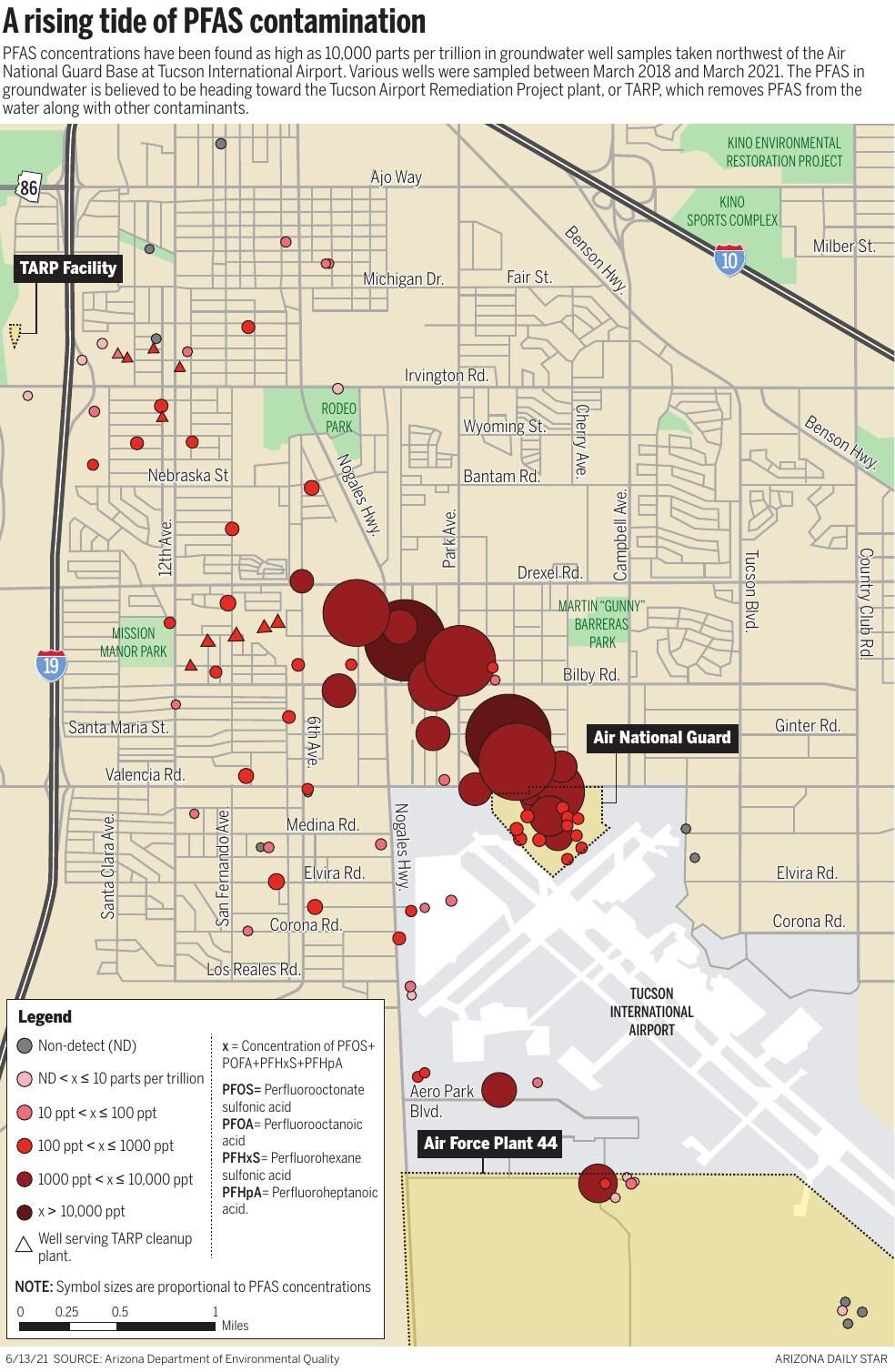

Now, three years after a family of toxic compounds known as PFAS was discovered in groundwater north of two Tucson military bases, it’s an open question as to when a cleanup of those chemicals will get underway.

There is a strong push from a bipartisan band of Arizona leaders to get a cleanup started. The push has accelerated since Tucson Water announced last Tuesday that it plans to shut down its Tucson Airport Remediation Project water treatment plant on the south side out of concern that rising PFAS levels could seriously harm its ability to treat these compounds.

But a number of financial, political and legal obstacles stand in the way.

The lack of federal regulation of PFAS compounds — despite a body of studies demonstrating a wide range of health effects — has stymied past efforts to get cleanups going near military bases here and around the country.

One reason is that federal agencies have declined to order cleanups when there’s no federal drinking water standard for the compounds and when the feds haven’t formally declared PFAS a hazardous substance, which under federal laws also must legally be cleaned up.

Congressional legislation to directly appropriate money for PFAS cleanups also hasn’t succeeded.

But there are some signs of hope, advocates for PFAS cleanup in national environmental groups such as the Environmental Working Group say.

First, the Environmental Protection Agency announced in March 2021 that it will start the lengthy and cumbersome process to set a federal drinking water standard for the two most commonly studied PFAS compounds, known as PFOS and PFOA.

It will take two years for the EPA to propose drinking water standards, the agency has said. Another 18 months will pass before it must approve standards.

PFAS

From

Second, U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Tucson said last week he’s optimistic about the prospects of securing federal funds for a PFAS cleanup this year through congressional action. Legislation to directly fund PFAS cleanups has bipartisan support although it failed last year.

Grijalva also hopes that funds for cleanups can be inserted into the National Defense Authorization Act, a bill that authorizes military spending each year and is considered “must pass” legislation.

“You’re having clean water issues all over the country, whether it’s in Flint, Detroit, or the south side of Tucson,” Grijalva said. “Both Republicans and Democrats are affected by this.”

With the impending closure of the TARP plant, Tucson's situation with PFAS is quickly approaching a crisis level, Grijalva said.

"Standard or no standard, Tucson residents deserve access to clean water, free from contamination." he said.

Bipartisan push

Bipartisan support for a PFAS cleanup was evident at a news conference Tuesday in Tucson when Tucson Water officials announced they will soon shut down their 27-year-old water treatment plant on the south side due to increasing PFAS levels in groundwater feeding it.

Standing next to utility officials, Democratic Mayor Regina Romero and Democratic Councilman Steve Kozachik was Misael Cabrera, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality director in the administration of Republican Gov. Doug Ducey.

It was ADEQ’s new map, showing that PFAS pollution was moving in high concentrations toward the water treatment plant, that was the “last straw” leading Tucson Water officials to decide to shut the plant down, said James MacAdam, a utility spokesman.

The contamination has not shut down any wells from which residents in south or central Tucson were drinking, so officials have said it posed no immediate health risk. Tucson Water has been delivering water from the treatment plant to 60,000 residents in the city’s urban core, but since 2018, the treated water has contained PFAS concentrations smaller than the utility’s equipment is able to detect.

On Wednesday, both Arizona U.S. senators and three Tucson-area congress members, all Democrats, wrote to Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin seeking immediate action by officials of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and the Air National Guard Base in Tucson to expedite investigations and cleanup of PFAS groundwater pollution near those facilities.

“Immediate action from all parties responsible for the PFAS groundwater pollution is needed to stop the spread of PFAS,” the letter said.

The Department of Defense has contributed to PFAS contamination of groundwater in the Tucson area for many decades, the letter said, and has failed to act as groundwater contamination continues to spread further into the Tucson community.

“The city of Tucson is doing everything it can to protect its residents, often at a great financial cost. It is past time for DoD to contribute to the solution,” said the letter from Sens. Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly and Reps. Grijalva, Tom O’Halleran and Ann Kirkpatrick.

About six weeks ago, Ducey also wrote Austin a letter urging the Defense Department to accelerate investigations and pollution cleanups at Davis-Monthan, the Air National Guard base here and at two Air Force facilities in the Phoenix area.

Crews lay pipe that will transfer water to the reclaimed water system and/or the Santa Cruz River from the Tucson Airport Remediation Project water treatment facility, 1110 W. Irvington Road.

“Ensuring that all Arizonans have the cleanest possible drinking water from public water systems today and for our future is critical for our health and well-being and a top priority for our state,” Ducey wrote. “Arizona ... is acting to contain the spread of PFAS now, and I ask you to make a similar commitment for prompt remedial actions to address the DOD-related PFAS contamination of groundwater throughout Arizona and protect the health and safety of Arizonans.”

Officials of the two air bases in Tucson have not publicly admitted that their use of firefighting foam containing PFAS from the 1970s into the mid- to late 2010s is responsible for the contamination found just north of the bases.

But most local and state officials involved in the PFAS issue have fingered one or both of the bases as culprits because of that widespread use of firefighting foam containing PFAS.

Noncommital response

But how quickly Davis-Monthan and the Air National Guard bases will begin cleanups remains quite unclear, based on statements various Air Force officials gave the Star last week.

First, the Defense Department’s response to the letters from Ducey and the Democratic congress members and senators was brief and noncommittal.

“The department has received both letters and will respond accordingly,” said Peter Hughes, a department spokesman, in an email Thursday to the Star.

Another Air Force spokesman, Mark Kinkade, told the Star on Thursday that “I would plan for early next week” for the Air National Guard to respond to several questions on its intentions for investigating and cleaning the contamination north and northwest of its 162nd Wing base in Tucson.

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base officials just started in April what they call a full-scale, remedial investigation of PFAS groundwater contamination in and around the base. Using a private contractor to lead the investigation, the effort will include sampling of surface water, groundwater, sediment and soil on the base through fall 2024, base officials say.

Also, Air Force officials plan to use sampling data provided by Tucson Water and the state to test additional private wells in the immediate vicinity of the base, base officials said on their website.

“The Department of the Air Force understands the community’s concerns and is working as quickly as possible to address those concerns,” said a base spokesman, Capt. Elias Small, in an email to the Star.

But Davis-Monthan officials say they can’t say now when a cleanup will begin near the base.

Small said the process of investigating pollution under the federal Superfund toxic waste cleanup program gives the Air Force the legal ability to address “any imminent and substantial threats to public health” by removing contaminants.

But before a complete cleanup can begin, a remedial investigation is a “required and necessary step” to identify and understand the nature of PFAS releases into the environment, Small said. It will provide critical information needed for determining possible long-term responses to the contamination, he said.

The investigation will collect data to characterize site conditions, determine the nature and extent of contamination, and assess potential risks to human health and the environment, Small said.

“These investigations and studies will take the Department of the Air Force one step closer to implementing long-term actions and will help us select the most effective cleanup option for each installation,” he said.

He said there’s no cleanup cost estimate yet but the base has spent $8.4 million so far on various investigative and cleanup activities on base property.

Also, in response to Ducey’s letter, an Air Force agency known as the Air Force Civil Engineering Center assigned a hydrologist to evaluate threats from PFAS compounds to drinking water near Davis-Monthan, said Arizona Department of Environmental Quality spokeswoman Caroline Oppleman.

In late May, Air Force engineering center officials also contacted ADEQ and proposed to join it in planning efforts toward installing a pilot project that will conduct the initial cleanup for PFAS compounds from groundwater north of Davis-Monthan, Oppleman said.

The pilot PFAS cleanup was supposed to begin this summer. But it’s been postponed because the manufacture of stainless steel vessels needed to operate the treatment system has been delayed due to increased demand, Oppleman said. The vessels are scheduled to arrive in November but ADEQ is evaluating temporary solutions so the treatment can start sooner, she said.

‘Could be years to decades’

At Tuesday’s news conference announcing the treatment plant shutdown, Assistant Tucson City Manager Tim Thomure said authorities have no timetable for when a full-scale PFAS cleanup facility will be online on the south side.

“It could be years to decades in order to deal with the problem, when environmental contamination like this occurs,” Thomure he said.

“It’s a forever chemical and it’s a forever problem,” said Thomure, referring to the phrase commonly used to describe PFAS because its chemicals don’t break down readily in soil or water.

Thomure also declined to predict the cleanup cost. The cost will depend on what type of treatment is done, he said.

“We’ve spent $39 million dealing with PFAS so far. We have not solved the problem. It’s 10s of 100s of millions of dollars for PFAS,” he said.

The longer the pollution sits untreated in the aquifer, the more it will spread, making it more expensive and difficult to clean up, officials said.

One thing clear is that Tucson Water ratepayers shouldn’t have to pay for this cleanup, Kozachik said at the news conference.

“When you combine the D-M plume with the one at Tucson International Airport, this is going to be way beyond the budget capacity of Tucson,” he said. “And from the standpoint of culpability, it’s the Department of Defense, and the firefighting foam they’ve been using, spraying into the ground.”

“All of of the above need to come to the table to make our city and ratepayers whole,” he said.

Deja vu for south-siders

For Yolanda Herrera, a longtime south-side advocate of pollution cleanup, the history of prolonged delays before TCE and dioxane cleanups began is scary as she looks ahead.

“There’s been enough research to know that PFAS is harmful to humans,” said Herrera, community co-chair of the Unified Community Advisory Board, a federally chartered group that oversees the south side’s groundwater cleanup. “I think that’s what’s frustrating the public, why it took so long with the others.”

When Herrera’s late father Manny Herrera first entered the political arena in the 1980s to fight for a TCE cleanup, he went to Washington, D.C., several times to visit congressmen and federal agencies to bring to light the problems TCE was causing, Herrera recalled. He was an original member of the advisory board.

“We lived and grew up where there was a contaminated well at the end of our street,” said Herrera, a lifelong south-side resident. “Daddy realized many on our street were getting sick and dying.”

Her father died in March at age 94. “You should see all the paperwork he had,” Herrera recalled. “He had boxes and boxes full of handwritten notes from meetings with every agency he could get hold of.”

But now, she said, “If you look at how long I’ve been volunteering on this thing, it’s almost like we’re taking steps backwards instead of forwards.”