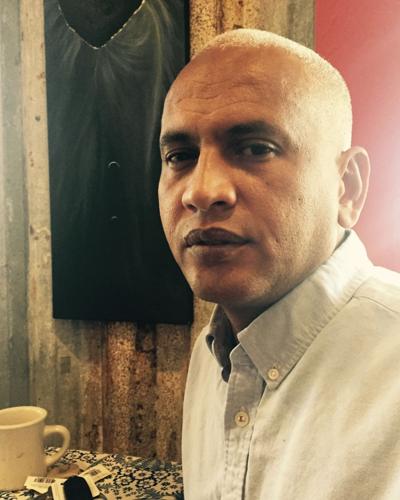

Though he’s traveled around the globe — the Middle East, southeast Asia, swaths of Africa, Pakistan are among the regions and countries he has visited — Ibrahim Younis is not a tourist.

Younis coordinates emergency relief efforts and security for the humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders, as its known in English. By his count, Younis has been to nearly 50 countries with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), its official name in French, and for the United Nations before joining MSF.

In his 25 years working for both international organizations, primarily with MSF, the Sudan-born Tucsonan has seen it all — misery, hunger, disease and death. Yet the 44-year-old Younis, married and father to twins, continues to travel to war zones, refugee camps and places hammered by natural disasters and disease.

“I’ve seen children hit by bullets. I’ve seen civilians being killed,” he said.

I can’t imagine.

Several weeks ago he returned from the conflict in Borno State in northeast Nigeria, on Africa’s western coast, where the extremist group Boko Haram has waged war on the government and civilians. The group, linked both to al-Qaida and the Islamic State, has made gruesome headlines with murder and mass kidnappings. There he was responsible for assessing security for the MSF operation, and oversaw the distribution of food and nonfood items.

Younis will give a public presentation about his work and that of MSF, Thursday, Nov. 10, at 1 p.m. at Pima Community College West Campus, Room J-G05.

Earlier this year he coordinated emergency relief teams working with refugees in Burundi in Central Africa and in Niger in the western side of the continent. He has worked in hurricane-ravaged Philippines and war-torn Syria and Iraq, in Ethiopia, South Sudan and in North Sudan, where he is from.

And where ever he works, there is one primary focus: people.

“Our job is to save lives,” said Younis, a U.S. citizen who speaks multiple languages: his native Arabic, English, French, Dutch, Indonesian and a smattering of other languages. “We look at all victims as patients first. We don’t ask.”

The neutrality of MSF is one of the legs of the tripod of principles that the organization emphasizes. The other two are independence and impartiality.

He said the elements are critical to MSF’s work and ability to navigate the constant shifting political currents between warring factions and governments. MSF doctors and personnel treat all combatants, regardless of whose side they represent, he said.

This and MSF’s emphasis on security keeps the organization’s personnel largely safe.

But at times, sadly, the precautions and impartiality do not prevent MSF personnel becoming victims themselves.

In August bombs killed at least 15 people, including medical personnel, in a MSF hospital in northern Yemen where a coalition led by Saudi Arabia is battling Houthi militias. A year ago this month the MSF hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, was bombed by an American gunship. Forty-two medical personnel, patients and other Afgans were killed.

Proximity to war is what makes MSF effective but dangerous.

Younis said he can’t dwell on being steps away from mortal danger. His thoughts have to be on saving lives, repairing bodies. “You make a difference,” he said while we talked in a coffee shop near the university. “It’s hard to let go.”

What also makes the 45-year-old international humanitarian group effective is that it does not take money from governments. Its multi-million dollar budget is completely supported by donations from the global community, said Younis.

When he’s not in a refugee camp or a war zone, Younis is home, working on MSF projects and with his world-wide contacts. He also takes classes at Pima Community College. He’ll transfer to the University of Arizona to finish his undergrad degree in political science.

His wife, a physician, is supportive of his work. She understands its importance. She was a MSF medical coordinator in Uganda where they met. They moved to Tucson about five years ago.

Younis is unsure how long he’ll continue to work for MSF. However, he won’t leave be anytime soon. He’s driven by MSF’s mission to save lives. He also wants to continue to advocate on behalf of the people he serves.

“Who will tell the stories of these people?”