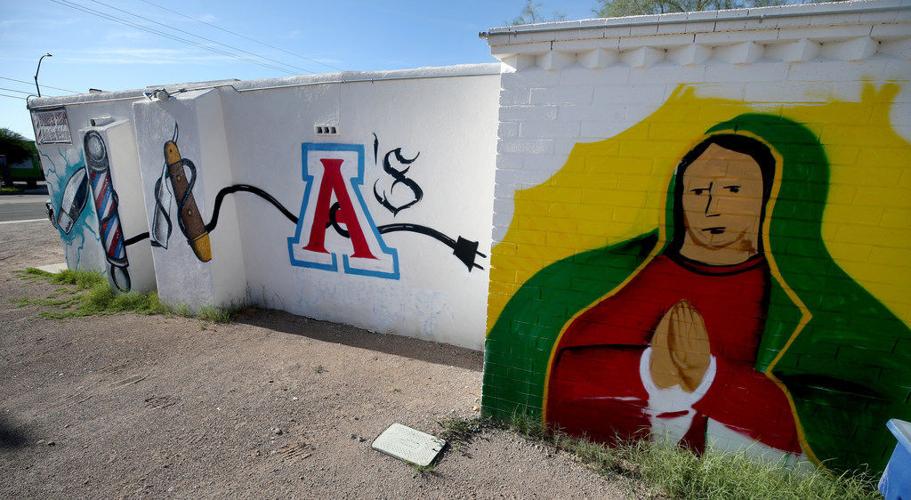

On the exterior of a barbershop wall in Barrio Hollywood on Tucson’s west side, there are two murals side by side. One is of the University of Arizona’s block “A” and the other is of the Virgen de Guadalupe.

The two symbols are first among equals in Tucson. They compete for our attention and they complement our sense of place. The pair are probably two of the most ubiquitous images in Tucson.

Images of the Virgin and the UA can be seen everywhere across Tucson and Southern Arizona but overwhelmingly in the barrios and neighborhoods where Mexican-American families have settled. They can be found on building walls, on decals adorning car windows and bumpers, on front porches enshrined in tiles or set in small home-made front-yard grottos, in framed photos or statues inside homes, on T-shirts and clothing, on bags, on pairs of earrings.

And on Sentinel Peak, where the most widely known “A” is visible across the valley, there, on the southeastern flank of the geographical landmark, la Virgen de Guadalupe sits in a small opening in the rocks, which can be seen from below where South Mission Road meets South Grande Avenue.

Representations of the Virgin and the UA are a Tucson thang. The images are sacred and secular. But sometimes the “A” is more sacred for religious UA fans and the Virgin is more secular as a cultural icon for her non-religious followers.

“Every family who lives here or if they have recently arrived, recognize the special way of the life and culture of this community,” said Celestino Fernandez, a professor emeritus at the UA where he has taught sociology for nearly 40 years.

The Virgin and the “A” are part and parcel of this community and increasingly so.

Now that the UA has increased its outreach to Latino families and recruited more students, that support for the university among Latino families has been strengthened, Fernandez said. Latino parents, who could not attend, are filled with pride that their children are there, or could be there if they chose to be.

“Throughout the history of the University the Latino community has been very supportive even if they weren’t able to attend,” said Fernandez, a scholar of Mexican immigration to the U.S. and of Chicano culture.

That includes Arthur “A.J.” Navallez, the owner of A’s Barber Shop. He had the murals painted on its south-facing wall at North Grande Avenue and West Ontario Street.

“I love Tucson,” said Navallez, who grew up in Barrio Hollywood, attended Mass at St. Mary Margaret Catholic Church on North Grande Avenue across the street from the barbershop, and loves the Wildcats. “This is home.”

For the 32-year-old Navallez, who is not a barber but is a corporate chef for Barrio Brewery, it was an easy decision to make, when he contemplated how he wanted to decorate the barren wall of his shop.

So, a little more than a month ago, Navallez turned to his tattoo artist, Esteban “Gordo” Voltares, to do his thing on the wall of the shop, which is attached to Lulu’s Express Your Hair, a beauty salon owned by Navallez’s mother, Marylou Quiroz, for about 30 years.

Navallez’s family supported the murals but the most important endorsement came from his nana. “My grandmother loved it,” he said.

Navallez, who did not attend the UA, said that both icons, the “A” and the Virgin, are more than images for him, as they are for many in his family and the barrio. They represent home, safety, faith and connection to others.

For many Chicano and Latino families, the Virgin occupies a key religious and social role. In Tucson’s households, images of Our Lady of Guadalupe are widespread. Almost every other house on the city’s south and west sides has some image, some representation of the Virgin.

For believers, the Virgin is said to have miraculously appeared to Juan Diego in 1531, 10 years after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, on which the colonizers built Mexico City. In the subsequent centuries the dark-skinned Mary has taken on various cultural and social hues. The Virgin is nearly synonymous with Mexican identity and is everywhere the Mexican diaspora has taken her.

While the UA is johnny-come-lately to Tucson, having been founded in 1885, its symbols have permeated Tucson. Many Mexican-American families identify with the university, almost religiously. Mexican-American fans are prevalent at Wildcats sporting events. And fandom runs several generations in many longtime families.

And it’s not just limited to Tucson. Go to Sonora and UA symbols can be found in homes of UA grads in Nogales, Magdalena de Kino and in Hermosillo, the state’s capital. Of course, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe also figures predominantly in Sonora. Tucson and Sonora are closely linked beyond flour tortillas and Sonoran dogs.

These two images will continue to be part of our urban landscape in this valley. The “A” will occupy its place of recognition and the Virgen de Guadalupe will hold her place of reverence. They set Tucson apart from other cities.

The “A” and the Virgin connect us.