Richard Lopez turned 94 last week. His room was festooned with balloons and birthday cards and he was resting in bed when I visited him Thursday morning.

Some of his 13 children and a couple of his many grandchildren were crammed into his room, which was filled with love on Valentine’s Day. They shared stories about the Lopez family patriarch, laughing and shedding some tears.

Lopez was dying in hospice, in Building 60 at the VA hospital on South Sixth Avenue. While his mind was sharp and his eyes twinkled, the body of the World War II veteran had given out. He talked in a whisper and his chuckles were only a bit louder.

“Where’s my cerveza?” he asked with a smile.

That’s the same question he asked when he came out of surgery recently, said the family. The Mexican beer Dos Equis is his favorite, they added.

On his left wrist, his watch gleamed with a colorful image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. A second, smaller image of the Virgin hung around his neck and lay on his chest. He said he is a believer — in the Virgin and in prayer.

He remembered a horrific night on a European battlefield. He was in a foxhole with other U.S. soldiers. Explosions and gunfire were coming from all directions. He said his prayers and emerged unhurt the following morning. He attributed his survival to his faith.

Lopez shared a few memories with me, and where there were gaps his sons and daughters filled in the missing details. Lopez’s family has been keeping vigil with him since he entered hospice the previous week.

Lopez was born in Douglas a couple of years before the Great Depression. He spent his early years in Bisbee and across the border in Agua Prieta, Sonora. In Douglas, his grandfather had a store on Third Street, three blocks from the U.S.-Mexico border. Lopez’s family lived next door. But when economic calamity struck, Lopez’s father, a construction worker, could not find work to feed the family, like so many others. Lopez’s family, like so many others, drove west to California. Lopez, the oldest of nine children, never went further than the second grade but taught himself to read and write, his family said. Lopez needed to work to help support the family.

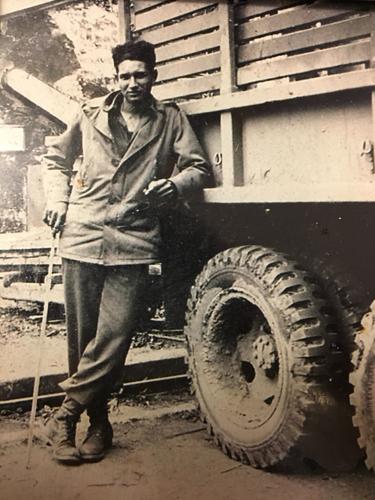

When he turned 18, Lopez went to war. It was 1943. The following year he found himself racing across Western Europe as a tank gunner with the 558th Field Artillery Battalion in the U.S. Third Army under Gen. George S. Patton.

“Old Blood and Guts,” Lopez whispered. It was the moniker that Patton’s own soldiers had given him.

Lopez, who also drove a supply truck in the war, synthesized his experience in a few words: He was a private first class who fired the gun. The corporal in the tank told him when to fire the gun.

“That’s it,” he said softly.

The War Department was just as succinct in its summary of Lopez’s military record: “Drove two-and-a-half ton army truck (6x6) in field artillery battalion in Europe theatre. Hauled ammunition over on paved orads (sp) and rough terrain.”

After the war, Lopez came to Tucson, where he met Alicia Garcia, the woman he would marry.

“Tata told me that one day he was driving a real nice car and saw nana with a friend,” said granddaughter Nichole Saldivar. “They stopped to talk to the girls.”

Lopez and his buddy followed the girls to a church, where he declared that some day he would marry that girl, Saldivar recalled.

They married in 1949 and started a family. He found work as a bricklayer. They lived in a small house near South Alvernon Way and East 32nd Street. Eventually the family would grow to 13 children and Lopez would find steady work building homes in a new subdivision south of Tucson called Green Valley.

Several of the 13 children went to Tucson High School. Others attended Salpointe Catholic High School, where Lopez donated his time and labor. Though they had a large brood, Lopez and his bride still found time to go dancing, said the family.

One of his favorite musical groups was the Mexican Trio Los Panchos, which was a sure sign that he was a romantic fellow. And he was a dapper one, too, going back to the early days after his Army discharge in Los Angeles when he bought himself two shark-skin zoot suits.

Lopez started his own construction company in the mid 60s but closed it in 1979 after he lost his beloved wife.

When he retired, he kept busy volunteering at a west-side nursing home and delivered Holy Communion to sick people.

In his final days at the hospice, Lopez received the Eucharist daily. And every day he received the love and caring and smiles from his extended family.

As I got up from his bedside, I told him it was a pleasure to meet him. He smiled back at me.

“It was good to meet you,” he said.

It was a memorable day to say adios.

On Saturday at 2 p.m., Pfc. Richard Lopez died.