What do you call a river in the desert, asked downtown-area resident Daryl Alderson as he sat on his bike along the freshly wetted Santa Cruz River just north of West Speedway.

“A miracle. And this, in a sense, is a miracle,” said Alderson, motioning toward where a small puddle of reclaimed water was inching northward Friday morning. It was four days after that treated effluent was first released into the river, maybe 2½ miles to the south, at West Silverlake Road.

Alderson’s “miracle” was a river that last week far exceeded expectations of the city officials who are trying to manage it. The Tucson Water utility had predicted the reclaimed water released Monday from a culvert pipe at Silverlake would flow no farther than West Mission Lane, about 5,000 feet north.

Instead, the water flowed more than five bridges north of Silverlake before finally slowing and narrowing a few hundred yards north of Speedway by Friday. River watchers were thrilled, and there were scattered signs of wildlife in the riverbed.

City officials had predicted a 10-foot-wide strip of water would run downriver at most for what they call the Santa Cruz River Heritage Project. But in some places, including at the West Congress Street bridge, it ran bank to bank.

That means the water probably isn’t recharging as quickly as planned — a key goal of the city’s Heritage project besides re-establishing the river’s natural habitat.

Still, “we’re very happy with it,” Tucson Water Director Tim Thomure said Friday. “Our estimate of it going to Mission Lane was based on what it could look like after a long time of release. With this initial release, we’ve been going at a full flow rate continuously since Monday, experimenting with how far that would reach.”

Pima County flood control officials had previously expressed concerns about the reclaimed water running to near downtown because of potential flood risks. They don’t want too much vegetation and sediment building up in the river channel because then, floodwaters could overtop the banks, they said.

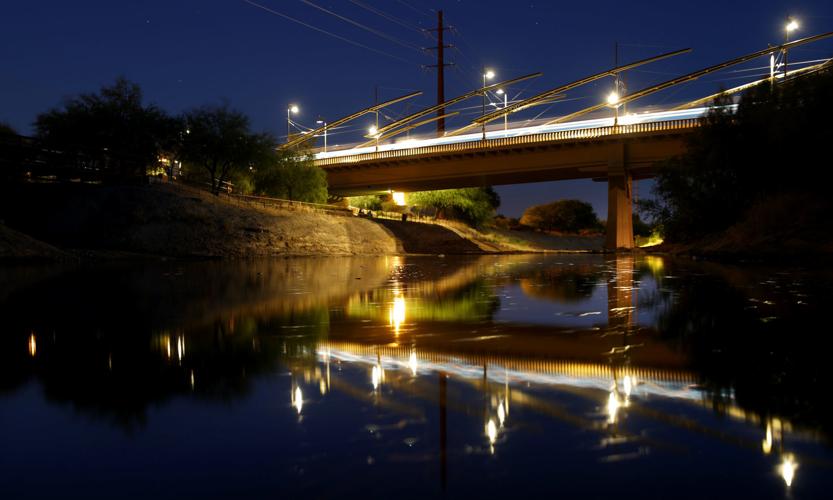

A westbound streetcar cruises over the Cushing Street Bridge over a wide pool of treated effluent in the Santa Cruz River. Different experts have different explanations for why the river is running farther than expected.

But they had no concern about the water rolling down the Santa Cruz near downtown last week. That’s because the amount wasn’t that much compared to what would flow if the city carried through its long-held goal to release a second pulse of water at Cushing Street just southwest of downtown.

“The amount of reclaimed water that Tucson Water is delivering into the Santa Cruz channel in the downtown area is negligible as far as channel capacity concerns go,” said Andy Dinauer, the Pima County Regional Flood Control District’s deputy director.

While the city still needs to deal with the issue that water releases will increase vegetation and reduce the river’s capacity to absorb floods, “otherwise, Flood Control is supportive of Tucson Water’s efforts and Tucson Water is very aware of the potential adverse/unintended consequences of their Santa Cruz Heritage Project,” Dinauer told the Star.

As of Friday, different experts had different explanations for why the river was running farther than expected.

But for Alderson, the sight of water was a happy reminder of rivers he used to see along bike paths he rode in the Chicago area. That’s where he spent most of his life before moving to Sahuarita a decade ago and to downtown Tucson last fall.

“It’s going to bring people here. For my environmental friends, I’m happy for them because it’s going to mean more trees for wildlife.

“Hopefully, people will become more aware of water, how valuable it is, how needed it is to sustain all forms of life,” Alderson said.

”A story of wildlife and trees”

Another happy river watcher was Kimberly Baeza, a 10-year Tucson resident. She took her 4-year-old son, Santiago, to the river south of Cushing Street on Thursday evening and both came away delighted.

“It’s something I’ve been hearing about for many years, but whenever I spoke with people in the know, they said it’s many years in the future,” Baeza said Friday.

Baeza said she thinks a wet river will make her Menlo Park neighborhood west of the river much nicer.

She sees the difference that water can make when she rides downstream of Tucson’s urban core to the two county sewage treatment plants at Roger and Ina roads. They have long deposited millions of gallons a day of effluent into the river.

“It’s a story of wildlife and trees. You can see so many more birds down there. It’s life in the desert,” she said, adding that now, “I’m really excited for us in this section of river. We will hopefully have a lush riparian habitat as opposed to a dry riverbed.”

Overall, the public reaction to the water release has been amazing and outstanding, Tucson Water’s Thomure said.

“People are not just excited, but they’re being emotionally touched,” said Thomure, saying he’s seen on social media a number of comments from people about how their parents and grandparents would talk about how they used to play alongside a flowing Santa Cruz River.

A number of dragonfly and damselfly species have been found along the newly flowing river.

Coyotes, toads and dragonflies

Already, signs of wildlife showed up on the river last week.

Several coyotes were seen along the river at various times, including one that passed by a reporter as he sat near the Cushing Street bridge Tuesday morning. Under West Star Pass Boulevard, swallows were darting about.

Downstream of Congress Street, a pair of native Sonoran toads were found mating in the river, said Doug Duncan, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist. Two nonnative turtles also showed up there, he said.

Last week’s biggest wildlife find came between Silverlake and Starr Pass, where University of Arizona researcher Michael Bogan found nine dragonfly species and five damselfly species in two days. He saw five species in the hours just after the water was released Monday morning, and the other nine species Friday.

Mostly, they were flying around, anywhere from a few inches to 20 feet above ground. They were eating small flies and other small insects.

“Anything that they can get in their mouth, they can eat,” Bogan said.

The males, usually more brightly colored in both species, would fly in circles around a spot in the stream they’d picked as their turf so no other males could come around, he said. As soon as a female would enter that zone, the male would try to grab onto her, hang on and then they would mate, said Bogan. He saw mating and egg-laying activity among 13 of the 14 species he spotted.

“I was really surprised,” said Bogan, an assistant professor at the UA’s School of Renewable Natural Resources. “If you pay attention in Tucson, you’ll see a dragonfly from time to time. They’re pretty good at flying. They get around pretty well. I wouldn’t have been shocked to see a couple of species, but I was really surprised to see that many species, especially damselflies.”

He went on to say, “Damselflies are smaller. Their wings are a lot weaker. They tend not to fly too far from the water. It usually takes them a lot longer to find a new habitat.”

He was heartened at watching the public interest along the Santa Cruz because while other reaches of water downstream of sewage plants have been flowing 30 to 40 years, “you never see that many people by the river. Yet the first day they turned on the river here, there were hundreds of people by the river. “People are connected to this flowing reach much stronger than the others,” he said.

Treated effluent entering the Santa Cruz at 29th Street has trickled north past Speedway.

The runaway river — Some theories

Eric Holler, a retired U.S. Bureau of Reclamation engineer, wasn’t surprised at the Santa Cruz’s rapid downstream movement but says it might not always flow that far north.

When he started work 15 years ago on a Central Arizona Project water recharge effort on the Tohono O’Odham’s San Xavier District, at first, the water ran a long way before starting to infiltrate much into the aquifer. Then, it started to seep in more quickly, he said.

The water has to first overcome what he called the “pore pressure” of the river’s soil particles, which prevents the water from seeping downward at first, said Holler, who retired from the bureau in 2014.

“You go outside, you haven’t watered for awhile. You put water out of your hose, and it puddles on top for a bit before soaking in,” Holler said. “But once it soaks in and overcomes that pore pressure, then it will soak in a lot faster.”

UA hydrologist Thomas Meixner suspects that fine grained layers of clay and silt, deposited in past floods, and lying beneath the ground surface today, could be blocking the river from recharging, he said.

This likely will change when Pima County flood control officials come in later this year and remove sediment and vegetation from the riverbed between Silverlake and Cushing Street, he said.

“That disturbance alone will increase the infiltration rate, at least for a period of time,” said Meixner, associate chairman of UA’s Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences Department.

Dennis Caldwell, a private consulting biologist, said he recalls seeing water quickly recharge at first along Cienega Creek in Las Cienegas National Conservation Area southeast of Tucson. But eventually, the water laid down an algal bloom on the ground surface that slowed, if not blocked, future recharge, he said.

Tucson Water’s Thomure said he’s heard all of these theories and says the traditional theory is that groundwater recharge slows when water has been in a particular spot for a long time. But on other city recharge projects, he said, officials have found that it actually increases over time.

On the Santa Cruz, he said he expects the water to start settling into the ground a bit more and recharge rates to increase as the water releases continue and the river’s soils grow more saturated.

“Right now, we are really in an experimental mode to see what it will do at full flow without any other intervention,” Thomure said of the river.

Under its current state permits allowing it to conduct this project, the city’s goal is to ultimately have the river flow reach Congress Street, he said. But if the river keeps flowing past Congress anyway, “you could certainly modify the permit.”

All he would have to do is work with Pima County flood control officials to make sure they’re OK with the river flowing past Congress Street, he said.

It won’t be known that this project is successful until the city can maintain the river’s flow for two years and demonstrate that the water is recharging the aquifer as the city wants, he said.

If that happens, “and if we’re able to see beginnings of a healthy riparian habitat, we’re confident to say this will be a success in the long term,” he said. “It’s obviously a success in the immediate term.”

Damselfly on the Santa Cruz River downstream from where effluent enters at 29th Street in Tucson.

A roadrunner on the Santa Cruz River downstream from where effluent enters at 29th Street in Tucson.