You could never tell if Tucson bluesman George Howard was having a bad day.

“He was always smiling. You could never tell what else was going on because he never brought his baggage to the stage,” said blues pianist Arthur Migliazza, one of the many young blues musicians Howard mentored in a music career that stretched five decades.

“He was always on the go and so cheerful,” added Rudy Barajas, who played drums in the George Howard Band for a decade.

Even Howard’s lifelong best friend, Sharon Shinn, had no idea that the cancer Howard had been quietly battling was at a point of no return.

“That was George. He didn’t want you to suffer because he was suffering,” Shinn said several days after Howard died in hospice care on Friday, April 14, at the age of 72.

Howard’s death sent shockwaves through Tucson’s music community, with dozens sending condolences on Facebook.

“George Howard was such a force of nature on our music scene,” wrote singer Crystal Stark. “... He always had his hand on the musical pulse of our city.”

“I can’t say enough about the contributions George has made to every single one of us in the Tucson music community,” blues singer/fiddler Heather Hardy chimed in. “But for me, he was just mainly a friend ... a deeply respected peer. ... Always positive. Always pushing to do more and include more people in what he did and just a damn good guy.”

“I think we spoke several weeks ago. I think I said ‘love you, man,’” Tucson rock drummer Bruce Halper added to the pages of social media condolences. “This is very sudden and sad. ... My heart aches for all of us.”

Howard’s death comes almost three months to the day after Tucson lost blues powerhouse vocalist Anna Warr, who occasionally sang with Howard.

George Howard photographs Paula Lahr in his Tucson studio in 2008. Howard was a musician and a photographer who trained his lens on Southern Arizona’s cultural diversity.

Howard was born in Asbury Park, New Jersey, and moved to Sierra Vista at the age of 3 in 1954 with his parents and two sisters. In elementary school, he played drums and became friends with Shinn, the only girl in the percussion section.

While attending Buena High School, Howard played sports and became enamored with photography, said his older sister Barbara Blankenship, who still lives in Sierra Vista.

He moved to Tucson after graduating and studied finance and business at Pima Community College, earning an associate’s degree that landed him a banking job. After a few years, he switched gears and formed Right Eye Photography. He started doing freelance work with magazines and other publications and photographed weddings and community events.

He also began forming bands, starting with the Statesboro Blues Band in the early 1980s that played at the old Chicago Bar, Terry & Zeke’s and a handful of funky Tucson holes in the wall — many of them long gone — playing everything from Cajun and zydeco to blues and funk.

Throughout his 50-year career, Howard worked with some of the country’s biggest stars, including John Lee Hooker, Bo Diddley, James Brown, Bobby Keys of the Rolling Stones, Johnny Lang, Albert Collins and Willie Nelson.

When he wasn’t on stage, he mentored young artists, including Migliazza, who was 12 when Howard saw him playing blues piano in the style of New Orleans bluesman Henry “Roy” Byrd, best known as Professor Longhair.

Migliazza, who has lived in New York since 2010, recalled Howard telling him that he had never heard anybody in Tucson play in that style. A year later, Howard got Migliazza his first public gig, opening for Buckwheat Zydeco at O’Malleys.

“I learned everything from him,” said Migliazza, who was part of Howard’s Roadhouse Hounds band while he was in college and collaborated with him including as a piano-drum duo. “I learned the importance of being a good person and somebody people liked to be around. I learned the importance of charisma.”

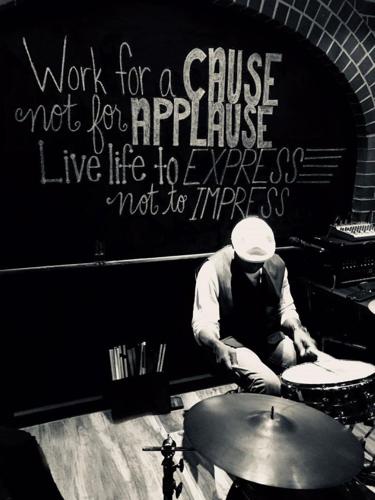

George Howard co-founded the Tucson Musicians Museum and played blues in town for decades. He also was a longtime commercial photographer.

In 2007, Howard and Susan French, the wife of a member of Howard’s Dr. Mojo and the Zydeco Cannibals band, formed the nonprofit Tucson Musicians Museum. Initially, it was an outlet to display Howard’s vast collection of band photographs that chronicled Tucson’s music scene. But from the start, it was Howard’s way of recognizing Tucson musicians and supporting the next generation through school music programs and mentoring young musicians.

Howard also launched the Tucson Musicians Hall of Fame to honor musicians who had been part of the Tucson music scene for at least 25 years. To date, 171 people have been inducted.

“I think the museum was very, very important to him,” French said. “We wanted to celebrate, preserve and perpetuate Tucson’s unique musical heritage, and that’s what we did.”

“He cared about the music community,” said David Slutes, Hotel Congress’s music director who booked Howard’s bands dozens of times over the years. “He was always concerned about getting the music in the schools. Besides being a terrific musician and a nice guy, he was putting music back in the community that supported him and that was his ultimate legacy.”

Shinn recalled a recent conversation with Howard following a show at Tucson Omni Resort. He told her he was going to miss performing. At the time, she didn’t know his health situation.

“I’m really gonna miss entertaining,” she recalled him saying. “I’m really gonna miss singing.”

“It’s a terrible loss,” Shinn said. “He brought so much charisma and energy into the world.”

Blankenship said she and Howard’s survivors, which includes his sister Allyne McFalls of Sierra Vista and 10 nieces and nephews along with nearly 50 great- and great-great nieces and nephews, will hold private services in Sierra Vista.

Hotel Congress, the Tucson Musicians Museum and the Southern Arizona Blues Heritage Foundation are collaborating on a celebration of life on the Hotel Congress Plaza at 4 p.m. May 21. Slutes said several Tucson musicians will perform tributes to Howard during the event.

Tucson Landmarks: Hotel Congress, 311 E. Congress St., opened in 1919 as a luxurious mainstay for visitors arriving in the Old Pueblo.

The downtown landmark has kept much of its history alive in the past century, while also bringing modern amenities to Tucson natives and tourists.

Video by Riley Brown / For the Arizona Daily Star

Contact reporter Cathalena E. Burch at cburch@tucson.com. On Twitter @Starburch