Previous attempts to use technology to secure the U.S.-Mexico border have blown through more than $1 billion and have missed their mark.

But border officials say they have it right this time. After several delays, the first phase of Arizona’s technology plan to secure the border is finished — and others will soon follow.

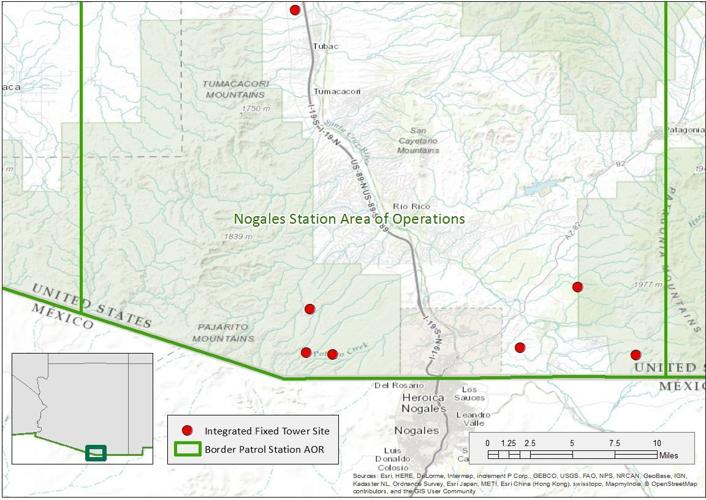

Seven of 52 planned Integrated Fixed Towers are functional in Nogales. The solar-powered towers are about 80 feet tall, with radar and day-and-night cameras that send real-time video footage to a Border Patrol command post.

Officials estimate they can start construction in Douglas and possibly Sonoita by January, after the Chief of the Border Patrol certifies that they work.

The towers are part of a larger Arizona border-surveillance plan announced in 2011 after the government canceled a failed $1 billion program. The plan includes a combination of ground sensors, long-range night-vision scopes mounted on trucks, binoculars, and fixed towers with and without radar.

The Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan is expected to be fully operational by fiscal 2020. That’s five years after the initial estimate, but CBP officials say that’s due more to future funding than to their ability to deploy the technology.

Once the entire program is completed, it will give the Border Patrol 90 percent situational awareness, which basically means knowing what’s going on, said Fernando Grijalva, assistant chief over the communications department in the Tucson Sector.

But first it must win approval from lawmakers, who are determined to avoid the mismanagement and cost overruns that brought down previous programs.

Tower system

The seven towers are high on the rolling hills east and west of Nogales, covering some of the area’s roughest terrain. While radar tracks movement, cameras let agents see what caused that movement.

The tower system is one of the final phases of the Arizona technology plan. So far, hundreds of underground sensors and dozens of mobile surveillance trucks have been delivered. Remote Video Surveillance Systems, which are also fixed towers without radar normally used in urban areas, have been added and upgraded at the Nogales and Brian A. Terry stations.

In March 2014, CBP awarded a $23 million contract to the American subsidiary of Israeli defense firm Elbit Systems, with the potential to extend to $145 million over eight years.

It was nearly a two-year process due to CBP receiving more proposals than expected, not having enough people to review them, a bid protest, the government shutdown and less funding, CBP reported to the Government Accountability Office.

Raytheon protested the bid, and the U.S. Government Accountability Office agreed, saying CBP’s “source selection decision lacks a rational basis” and that the agency didn’t evaluate proposals equally. After a five-month delay, CBP awarded the contract again to Elbit, and installation of the cameras began in October 2014. The last tower went up in March.

Agents say that, so far, it seems to do what they need it to do. CBP ran two tests, the last one concluded in September, to see if Elbit delivered what it had promised and to measure its effectiveness.

The solicitation called for sensors that can detect a single person and provide high-resolution video at a range of 5 and 7.5 miles during the day and at night and with sustained winds of up to 10 miles per hour.

It should also be able to tell whether someone is carrying a backpack or a long-arm weapon — even if the person is walking, riding an animal or on an ATV.

“We are able to see in areas we weren’t able to see before. It’s like turning on a light switch,” said Jose Verdugo, Border Patrol agent and operator in the Nogales station.

It can also help keep officers safe, he said, because by the time agents respond, they have a lot more information about what they are dealing with.

So far, smugglers haven’t changed their tactics to try to avoid the new cameras.

“They still try to hunch down low, roll across the road, find our blind spots,” he said, “techniques they’ve used since we’ve had cameras.” Agents still find suits made of dry grass meant to confuse the cameras.

And while traffic is always shifting from one place to another, officials said the cameras were installed in areas that are consistently busy.

“Terrain, geography and threat dictates tactics and equipment you use in any given area,” said former Tucson Sector Chief Manuel Padilla. He recently took over the Rio Grande Valley sector in Texas.

While mobile technology is critical to following traffic trends, he said fixed cameras offer a permanent solution.

It’s also an issue of manpower, Verdugo said. It takes up to eight agents to monitor the 23 fixed cameras in Nogales. If those cameras were mounted on trucks, operating them would require 23 agents.

Not spying on locals

While most of Nogales’ fixed camera towers are within five miles of the border, one of the new fixed towers is about 20 miles north, near the Border Patrol checkpoint by Tubac. That has some residents concerned with privacy issues and what they see as the militarization of the border.

“There was no advance notice or community vetting of the thing. It just went up,” said Jim Patterson, president of the nonprofit Santa Cruz Valley Citizens Council and longtime Tubac resident. “It’s one more step in really turning our community into an outpost of the Border Patrol’s mission.” The group is also involved in efforts to remove the I-19 checkpoint.

The Border Patrol says the cameras are there to secure the border, not to spy on local residents.

“Our priority is not to look in people’s windows or backyards to see what they are barbecuing,” Verdugo said.

A supervisor always monitors what agents are doing and a peer system puts multiple agents in the control room operating the same camera, he said. It takes three agents to operate one Integrated Fixed Tower.

No matter how they operate, the towers do not enhance the looks of Tubac, which is dependent on tourism, Patterson said.

The first thing visitors see when they cross the county line, he said, “is something that looks very military in nature.”

Seeking accountability

The Integrated Fixed Tower program is the federal government’s latest attempt to create a “virtual fence” to secure the border.

From 1998 to about 2005, the Department of Homeland Security spent $429 million in border surveillance systems that were set off by the movement of animals, trains and wind, the department’s office of inspector general said in 2005.

One of the most expensive initiatives was the Secure Border Initiative net, a virtual fence that covered 53 miles at a cost of about $1 billion from 2005 to 2011. The two systems of 15 fixed towers are still operational in the Tucson sector.

Last year, top CBP officials estimated the total cost for the Arizona plan at $500 million to $700 million, including operation and management for 10 years.

When the plan was unveiled, the federal Government Accountability Office said CBP hadn’t adequately explained how it determined that strategy is better than other alternatives. It also hadn’t defined the mission benefits expected, the GAO said.

In another report last year, the congressional watchdog found that CBP lacked an integrated master schedule for all components of the plan, that it had not independently verified total life-cycle cost estimates and that its plan did not call for testing towers in different weather conditions.

In contrast to previous initiatives, CBP said, the Arizona technology plan uses technology already being used elsewhere. Also, prospective contractors were required to show the government that their proposed systems were ready to use before it awarded a contract for the Integrated Fixed Towers.

Going forward, the agency says it will update long-term cost estimates by the end of this year and will measure the effectiveness of the new technology by the end of fiscal 2016 now that it has implemented a record-keeping requirement.

Republicans Rep. Martha McSally and Sen. John McCain introduced a bill they said would improve the management and accountability of new border technology.

The Border Security Technology Accountability Act of 2015, which passed in the House this summer, would require each border technology acquisition program over $300 million to have baseline cost, schedule and performance targets. The bill follows numerous reports showing DHS acquisition programs are a “high-risk” for waste, fraud, and abuse, McSally said in a news release.

“Southern Arizonans are demanding better border security,” she said, “and they expect us to do it in the most cost-effective and efficient way possible.”