After cutting ties to a controversial federal border-protection grant last year, the Pima County Board of Supervisors will consider whether to accept nearly $1.5 million in new funding from the program.

Last year, as with the previous 12 years, supervisors voted in February to accept federal funds under Operation Stonegarden, which provides money to law enforcement agencies for overtime, equipment and mileage related to border-security operations.

But following national discussion of federal immigration tactics, including the widespread separation of families at the border, the supervisors reevaluated Pima County’s position on the issue and changed course, voting in September to cancel the grant.

Despite the controversy, the Pima County Sheriff’s Department applied for 2019 funds and was awarded more than $1.4 million. The grant acceptance vote is on the May 7 agenda, with at least one new and questionable addition to the application: Vehicle-mounted license-plate readers.

The readers would be mounted on patrol cars, and not only would they be useful during Stonegarden deployments, “but the collection of plate data then becomes available for future investigations regarding location and movement of suspect vehicles,” the grant application said.

The Sheriff’s Department plans to use the Vigilant LPR System, the same database that’s also available to the U.S. Border Patrol, according to the application.

The operational guidelines are to be determined since the funding is still uncertain, but Sheriff Mark Napier said he expects the readers would be on all the time when patrol vehicles are in motion.

“They’ll be reading plates for the purpose of identifying patterns of traffic, which frequently drug traffickers and human traffickers have these patterns over time,” Napier said. “But also for a broad array of public-safety goals, among them recovery of stolen vehicles and identification of wanted people.”

Until the readers are up and running, and the Border Patrol has weighed in on what type of information it would like to have, Napier said he won’t know what information will be shared and what agencies it will be shared with.

The use of license-plate readers is becoming more common across the country. The technology is new to the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, which already has some deployed, Napier said.

“You don’t really have a right to privacy driving down the street,” Napier said. “The license plate belongs to the state and you’re on a state thoroughfare or government thoroughfare, so there’s not a tremendous expectation of privacy with respect to the plate information.”

The total cost for six license-plate readers amounts to just over $100,000, according to the grant application.

“MASS-SURVEILLANCE TECHNOLOGY”

Vigilant Solutions’ website says that each plate image captured along with the data is stored in the company’s Virginia database as a record that can be searched “only by authorized personnel.” The site goes on to say that each agency owns the data it generates and can decide whether to share it with other agencies.

Last month, the Marana Town Council voted unanimously to accept roughly $300,000 in Stonegarden funding. The Marana Police Department’s application for funding includes money to purchase of one license-plate reader.

“License-plate readers are a mass-surveillance technology that collects information on everyone, regardless of whether they’re suspected of being involved in a crime,” said Dave Maas, senior investigative researcher with the San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to defending civil liberties in the digital world. “Oftentimes the thought for law enforcement is, ‘We’ll collect this data on everyone in case maybe one day they commit a crime and then we can turn this into a time machine and scroll back and see where they were.’”

The information can reveal a lot about someone. If the patrol vehicles with the readers are driving past a Planned Parenthood, mosque or immigration law center, they’re gathering data about people and things that are none of the government’s business, Maas said.

As Napier did, law enforcement agencies often claim that people don’t have an expectation of privacy on the street, Maas said.

“What I counter with, is you tell me how the public would feel if a police officer was positioned at a mosque writing down the license plates of everyone going in ... or if police were just following people around all the time,” Maas said.

Using the databases that law enforcement has access to once the plate readers are purchased, officers can collect historical data and search places where a person has been, and they can search vehicles that have visited a specific address and even add someone to a “hot list” and get real-time alerts whenever the person is seen by a camera, Maas said.

Situations have also arisen where agencies haven’t put in an effort to protect the data they’re collecting, allowing live access to feeds from the plate readers, according to Maas.

Vehicle-mounted readers can be more problematic than fixed readers, since law enforcement can use them to canvas specific neighborhoods, leading to a propensity for disproportionate surveillance, Maas said.

“In Tucson, there are certain neighborhoods that are lower-income and maybe have a little bit more crime than other neighborhoods,” Maas said. “What’s going to happen is that (patrol) cars that visit those neighborhoods will be collecting more data, and using that data to investigate more crimes in that neighborhood. As they investigate more crimes in those neighborhoods, their cars are going to go there and collect more data.”

This creates a cycle that because more data is collected from specific neighborhoods, policing may shift to those areas, leading to racial or income disparity.

“You could be a total upstanding citizen who’s gone your entire life not even getting a speeding ticket, but if you live in a neighborhood that has a bit more crime, you’re going to have a bigger privacy violation than someone who maybe has a bunch more criminal involvement but happens to live in a wealthier neighborhood,” Maas said.

Vigilant Solutions, the company that PCSD intends to use, is particularly problematic compared to other plate-reader companies, said Maas.

Unlike other companies, Vigilant has its own contractors who collect data and sell it to law enforcement agencies, but also to debt collectors, insurance companies, banks and private investors.

EFF discovered that Vigilant installed plate readers on security vehicles at a mall in Orange County, California, and became concerned that it might be selling the data to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Months after Vigilant called EFF’s questions fake news, ICE released public data that confirmed foundation suspicions, Maas said.

Vigilant also has a standard series of clauses in its contract with law enforcement that limit how much agencies can speak about the product.

The non-disparagement clause says agencies can’t say anything negative about the product without written permission from the company. This becomes problematic when a local government wants candid information about whether the product is useful. If there are any problems, law enforcement agencies are legally prevented from talking about it.

The non-publication clause prevents law enforcement agencies from speaking to the media or providing public records about the plate readers or data collected without written permission from Vigilant, Maas said.

REJECTION RECOMMENDED

In September, shortly after voting to reject Stonegarden funding, the Board of Supervisors established the Community Law Enforcement Partnership Commission to review and make recommendations on grants and grant applications received by the Sheriff’s Department.

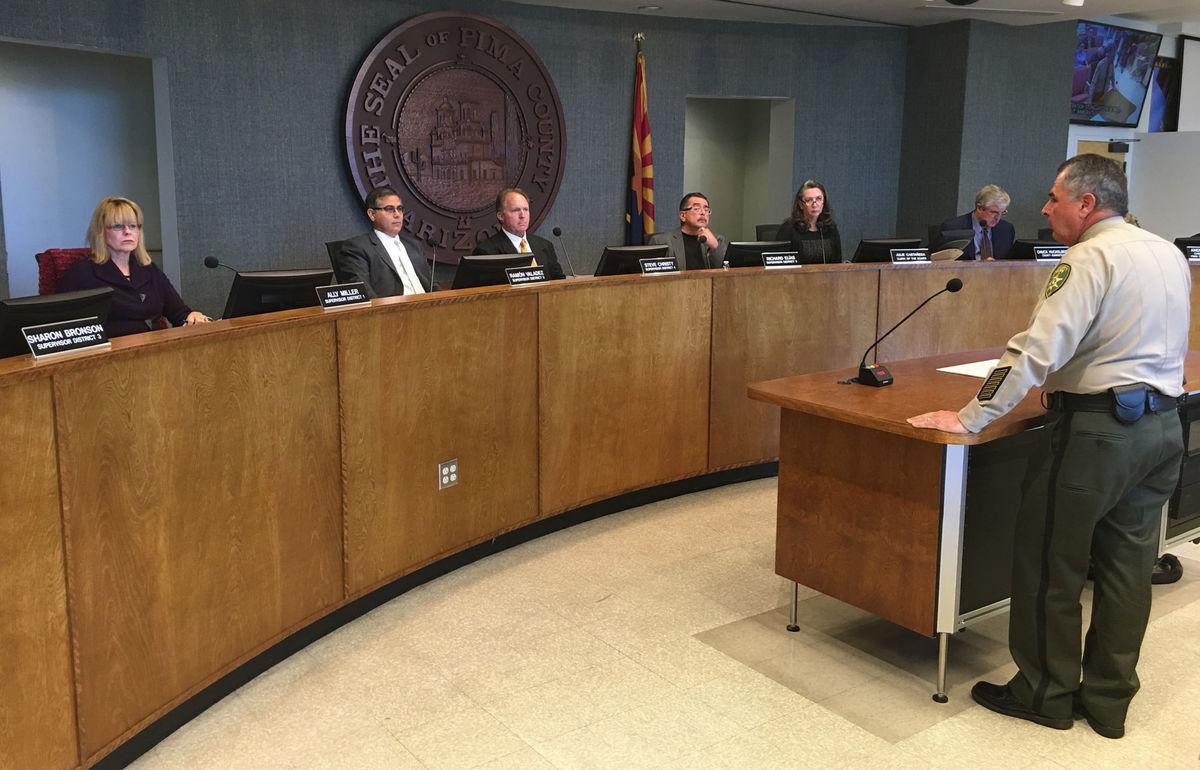

The commission has been meeting bimonthly and convened on Monday to consider whether it should recommend that the board vote to accept this year’s round of Stonegarden funding. Napier attended the meeting, speaking to the commission and taking questions from members.

“I’m hopeful,” Napier told the Arizona Daily Star before the vote. “We’ve done the very best we can to make the case. A lot of their questions were really more because they don’t understand things, and that’s not their fault; I should understand my business better than they do.”

Ultimately, the commission voted 6-4 to recommend that the Board of Supervisors again reject the funds.

Commission chairwoman Kristyn Randel, voted against accepting the funds for a variety of reasons, including PCSD’s lack of transparency when it comes to basic information about Stonegarden deployments, she said.

Randel said she previously requested information about how many vehicles were stopped, citations issued, people turned over to the Border Patrol and total arrests during Stonegarden deployments. In the reply, which came directly from Napier, Randel was told that the information she requested isn’t captured and isn’t required under the grant.

Randel has since learned that both facets of the department’s answer were not true, in that the federal government does require the tracking of such data, which PCSD already collects.

Randel also has concerns about the department’s staffing levels.

“They’re woefully spread way too thin,” Randel said, adding that deputies are performing required overtime at the jail and for covering regular patrol shifts.

“They want this money to do more overtime to do a federal immigration job, when that’s adequately staffed. I think it’s unfair to the deputies.”

During the commission meeting on Monday, Randel asked Napier if desert rescues and drug-interdiction missions would still occur if the Sheriff’s Department doesn’t receive Stonegarden funding. Napier said they would.

“He’s basically saying he’s still going to do the work Stonegarden would do,” Randel said. “So we don’t need Stonegarden money.”

Randel also expressed concerns about the department’s request for license-plate readers for patrol vehicles, saying that there’s a lack of oversight when it comes to the information being collected and shared with a database that federal authorities have access to.

“I have a problem with the indiscriminate collection of this data and what it’s being used for,” Randel said. “And PCSD can’t answer how Border Patrol will be using that data.”