Mother Nature takes care of the fruit trees at Oscar Carrillo’s south-side house whenever it rains.

Mother Nature sends storm runoff into a constructed rock channel that winds through his front, side and backyards. The channel contains the fruit trees that have stood up to eight years.

But Mother Nature doesn’t work alone. It took a recent $700 loan from a nonprofit group and a $500 rebate from the city of Tucson to buy 50 tons of rocks that fill Carrillo’s yards and direct this monsoon season’s ample runoff to the trees. The rocks create “earthworks” — a low-tech form of rainwater harvesting that grades a yard to direct runoff.

This activity and the storing of rainwater in cisterns has been on the rise in Tucson since the city started awarding water-harvesting rebates in 2012 to homeowners.

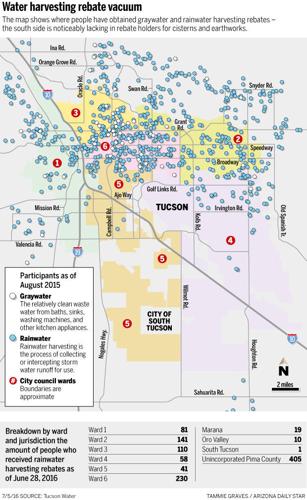

As of June 28, close to 1,100 residents had received rebates totaling $1.44 million. Another 99 residents received $41,000 more for gray-water systems directing laundry water and other household wastewater to trees and gardens.

But Carrillo, who says he has been disabled with polio and out of work since 1983, is a rare breed on the south side.

Only 41 homeowners in City Council Ward 5, where he lives and which includes the south side, have received rebates. That’s the least of all six wards.

Ward 5 also ranks last in many economic indicators, including number of families living in poverty and median household income, a 2012 city of Tucson report on poverty and urban stress shows.

Such families can’t afford the cost of rainwater harvesting, even with rebates, some council members say. A cistern rebate tops out at $2,000 and earthworks fetches $500 — but the projects often cost much more.

Ward 6, which led with 230 rebates, isn’t wealthy as a whole, but has affluent pockets, such as the Sam Hughes neighborhood.

More than 400 rebates have been issued in the upscale Catalina Foothills and other parts of unincorporated Pima County that are in Tucson Water’s system.

More than 18 months ago, the council voted unanimously to get more low-income residents into the rebate program, including spending $300,000 for a low-income loan program. But the program still hasn’t started although its money is in the 2016-17 budget.

On Wednesday, the council will learn how to increase low-income participation from the director of a group specializing in environmental justice. The Sonoran Environmental Research Institute wants to participate in the loan program as it has provided numerous such loans, including Carrillo’s.

“This rainwater harvesting rebate program is one of the best in the nation,” said Ward 2 Councilman Paul Cunningham, one of two to request the institute’s appearance. “The idea that we’re not promoting it more and making it more available to people is unacceptable.”

Cunningham wants more conservation measures to get Tucson’s per-person water use to 50 gallons per day by 2032. That would be down from 80 gallons today, well below the levels of the 1970s and ’80s.

But that’s not possible if “we don’t do the rebate program in a fair and equitable way,” said Ward 1 Councilwoman Regina Romero, who joined in inviting the research institute.

Recently, her office held a roundtable discussion with the research institute, the Community Food Bank and Tierra Y Libertad, all groups serving low-income persons, to explore ways of broadening the rebate program. She sees rainwater harvesting as a tool to combat inner-city, urban heat-island impacts by supporting the planting of shade trees in poor neighborhoods that don’t have many now.

“We said, ‘We need your expertise. What can we do as the Tucson Water Department to make sure we’re getting information to people that need it and can take advantage of it?’”

Working for environmental justice

From its small office near Grant and Country Club roads, the Sonoran Environmental Research Institute has worked for more than 20 years on environmental justice and health issues.

They’ve included improving families’ household environments by conducting home visits, reducing childhood lead poisoning, promoting tree planting, preventing falls among seniors, helping communities with air-quality permit issues and conducting air monitoring of toxic chemicals.

It’s used a year-old, $30,000, Environmental Protection Agency grant to set up a pilot rainwater harvesting loan program, said Ann Marie Wolf, the group’s director.

It’s given out 16 loans totaling $13,225 for water-harvesting systems. It’s used donated money for the loans because the EPA grant went to do research for and start up the loan program.

Today, the institute is “maxed out” with loans, with 39 families on a waiting list until more money arrives, she said.

It has also paid outright for 32 more earthworks systems using grants from the State Forestry Division and Tucson Water, Wolf said.

To get loans, homeowners must attend the research group’s workshops. More than 100 lower-income families have attended so far, Wolf said. The families must meet federal low-income guidelines — no more than $45,000 for a family of four.

They must also show they pay property tax bills on time. They agree to turn over three years of past water bills and to provide three more years of future bills so the institute can monitor their water use.

Families have up to a year to pay back the zero-interest, no-collateral loans. No family is behind schedule, Wolf said.

While 70 percent of Ward 5 residents were Hispanic in the 2010 census count — compared to 41 percent citywide — Wolf said she’s observed no cultural barriers keeping such residents from harvesting the rain.

But, “when we visited the homes for environmental health reasons, we saw a lack of trees there,” Wolf said. “We’ve since given out 2,000 trees to neighborhoods.

“We went back and analyzed 1,500 trees we’d given out. We found a 50 percent mortality rate. When we asked families why the trees died, a lot thought it was because they hadn’t gotten enough water,” Wolf said.

Families sign a contract with the research group and can approve their contractor for the installations. But most families do the work themselves, Wolf said.

The food bank has installed 10 gray-water systems to support gardens for low-income households in the past year. It plans to install another 10 this year plus 10 rainwater tanks, said Luis Herrera, the bank’s garden program coordinator.

After helping 240 low-income families plant gardens in the past seven years, the group is also interested in the rainwater loan program, he said.

“We’re trying not to get their bills to go up, and to conserve water,” he said. “Part of our goal is also to increase food production and plant trees that can use less water and take the heat.”

Family and friends worked hard

Carrillo used the labor of family and friends — two brothers, two friends, his wife and himself — to dig in the rocks and channel.

“It took three days, working 14 hours a day,” he said as he stood in the rock yard that surrounds the family’s three-bedroom brick house. “We’d get together at 3 to 3:30 a.m. and work.”

It wasn’t just saving water or money that caused Carrillo to seek the loan and rebate, he said. “We figured it would make our property look a lot better. We were getting tired of having a dirt yard.”

Now, the family has nine months to pay the loan back, at about $77 a month, he said — “it’s something we can afford.” While it’s too soon to say if the rainwater will cut his water bills, he said he feels pretty good about his new setup because “we’re getting pretty good rain.

“It does the work for me,” he said.

Reasons loan program hasn’t started

So why hasn’t the city water-harvesting loan program gotten started?

First, the city lacked money in its budget to start the loan program back in 2014, Tucson Water spokesman Fernando Molina said.

Second, Tucson Water wanted to spend some time working with the research group on its pilot project, he said. At the time of the 2014 council vote, the utility was developing its own pilot project to address lack of participation in water harvesting by the low-income community, Molina said.

Tucson Water has a history of working with Sonoran Environmental Research Institute (SERI) going to back to 2003 on various projects in low-income and Spanish-speaking neighborhoods, he said. Utility officials felt it was appropriate to enter into an agreement with the institute to conduct these small projects, even though that would delay things.

“While it may appear that nothing has been done with respect to developing these programs, you can see that we have been busy with (the institute) as they (investigate) the best way to move forward with these programs,” Molina said.

Cunningham and Romero don’t buy the utility’s explanations.

“We’ve gone through two water directors and hired a new (city) manager since then,” Cunningham said. “There’s an antiquated culture that exists in a small contingent of the people who work in the water department, people who have an antiquated way of thinking about conservation as a secondary part of what the water department does.”

More recently, however, under new Tucson Water director Tim Thomure, Cunningham has seen a shift in thinking to make conservation a primary concern, he said.

Under Thomure, the department, formerly cool to rainwater harvesting, now publicly supports it. Molina acknowledged that Tucson Water’s culture is changing. It’s retooling its conservation program to also include demand management, stormwater capture and reducing water system losses.

“It’s going to be more of a water sustainability program,” he said.