NOGALES, Ariz. — It’s been nearly three months since troops first showed up at the Southern Arizona border, placing razor wire atop the fence and blocking some port lanes in anticipation of Central American caravans that instead went to the California line.

As more troops are being deployed to the border, locals here are calling for the razor wire to be removed, saying it hurts businesses and sends the wrong message.

“In Nogales we are used to seeing the federal government make decisions about our surroundings,” said Evan Kory, whose family owns Kory’s and La Cinderella stores in downtown Nogales. “But the razor wire was way more aggressive than anything we had seen, which scared me. It felt like it was out of our hands as a border community. You feel powerless, like your voices aren’t heard.”

About 3,500 additional active-duty service members will be sent to the border as part of a new request from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security that extends their mission through the end of the fiscal year. There are about 2,300 troops currently deployed, down from 5,900.

In Arizona, there are about 650 troops assisting Customs and Border Protection, down from the 1,500 originally deployed in the beginning of November. That’s in addition to hundreds of National Guard troops activated since April.

Across the U.S.-Mexico border, the projected cost of the deployment of the National Guard is $550 million through the fiscal year, Department of Defense officials said at a Jan. 29 congressional hearing. So far another $132 million has been spent on the active-duty military on the border, and officials said they couldn’t estimate the full fiscal-year cost.

While the soldiers were initially tasked with helping CBP strengthen ports of entry and working on logistics and transportation, the new mission focuses on surveillance and placing 150 miles of additional concertina wire away from the ports. So far, they’ve laid 70 miles of the wire near ports in Texas, Arizona and California.

On Saturday, the Nogales International newspaper reported that more troops were already in town adding wire. As many as six rows can be seen coiled across a section of fence in an image posted on social media.

Army troops were back in downtown Nogales on Saturday, adding more coils of concertina wire to the border fence. pic.twitter.com/uALL9xTztf

— NogalesInternational (@nogalesnews) 3. Februar 2019

Initially, most Arizona ports of entry had about one mile of the wire on either side, CBP said.

During U.S. Sen. Martha McSally’s recent border visit, Nogales Mayor Arturo Garino brought up the wire issue.

“Of everything we talked about,” he said he told the Tucson Republican senator, “the easiest thing you can help us with is to remove the concertina wire.”

In a news conference later that day, McSally said conversations were ongoing “about what’s actually needed to keep the community safe and promoting cross-border commerce.”

Border Patrol officials said the agency is “constantly evaluating operational needs ... but currently there are not plans to remove the c-wire.”

Last week, troops did remove the containers they had placed to block two northbound lanes at the DeConcini Port of Entry in Nogales.

In Laredo and Hidalgo, Texas, soldiers have removed some of the barbed wire after local leaders raised concerns.

Garino is not ready to give up, he said, and his next move will be sending letters to Washington, D.C.

“Aesthetically pleasing it is not for a community that trades with Mexico, for a community that depends on the residents of Nogales, Sonora, that shop here,” said Garino, who successfully fought off plans to put up razor wire in 2013. “It looks like a prison, it doesn’t look right.”

Sheyla Machado, 13, seeks an opinion from her mother, Francisca Gomez, as she tries on a quinceañera dress at Kory’s in Nogales, Ariz. Gomez, who crosses the border daily, says when razor wire appeared last year, she was afraid she might get stuck on one side or the other.

Fear cited

Francisca Gomez, 37, crosses the border every day, even multiple times a day.

Her family lives and works in Ambos Nogales. Her children go to school on the Arizona side and she sells goods she buys on the U.S. side in Nogales, Sonora.

But on Nov. 6, when troops in fatigues showed up and started to place the razor wire on top of the fence, she wasn’t sure she wanted to take the risk. She was afraid she would get stuck on either side.

“There were a lot of rumors that they were going to close the port of entry, a lot of people didn’t want to cross,” she said.

“It was intimidating to see the soldiers,” she added. Residents wondered what was going on. What could be so bad that the government had to deploy the military to the border?

Gomez’s daughter, Sheyla Machado, was a little scared at first but then she felt angry, the 13-year-old said as she tried on quinceañera dresses at Kory’s. The bridal shop opened by Evan Kory’s grandmother in 1968 sits right across from the Morley Gate, a pedestrian crossing in downtown Nogales, from where the razor wire is clearly visible.

Sheyla said her class often goes to the port of entry to play with the children and talk with the families waiting to present themselves to seek asylum. She didn’t like the image the U.S. was portraying.

“To me the border is a very calm place,” she said. “There’s not a lot of crime; it’s beautiful.”

On Nov. 9, officials held the first news conference since the deployment of the troops to Southern Arizona. They said there were thousands of mostly Central Americans traveling en masse and the U.S. government didn’t know where they were going to try to come through.

“I think everybody saw what happened on the Mexico-Guatemala border, where Mexico was in fact offering asylum and they still rushed through the border. So we have to prepare for that eventuality,” Rodolfo Karisch, then commander of the Joint Task Force-West, told reporters.

Some migrants in the groups traveling north had burst through the Guatemalan border fence and clashed with Mexican riot police.

Mark Adams of Frontera de Cristo says a colleague doesn’t want to cross the border because of the “psychological impact.”

In Nogales, in addition to the wire on top of the border fence, troops placed the containers topped with wire to block some northbound port lanes and helped CBP conduct readiness exercises in which officers in riot gear practiced blocking lanes.

In the Arizona border town of Douglas, Mark Adams, who heads the Presbyterian binational ministry Frontera de Cristo, said soldiers first started to put up the wire and block a lane with a container and more wire — right by a sign that reads “Welcome to the United States” — in mid-December.

“We had a delegation visiting from Nebraska seeing the military putting up the concertina wire on the wall and one of the folks said ‘this looks like a war zone,’” he said.

For the most part, the migrants and asylum seekers never showed up at the Sonora-Arizona border, with most of them heading to Tijuana, the border crossing they had announced they would use as their base.

Evan Kory, whose family owns Kory’s, above, says the razor wire “was way more aggressive than anything we had seen. ... It felt like it was out of our hands as a border community.”

Resources

Some local residents and elected leaders question the need to deploy the troops at a time when apprehensions are at historic lows.

“I knew it was supposedly meant to stop an ‘invasion’ of folks coming from Central America to ask for asylum at the ports of entry, folks who weren’t coming across illegally ... and not even coming to Agua Prieta or Douglas,” Adams said.

“Instead of addressing the real root causes of what was going on and the real issues like the asylum process, we spend money on fortifying an already divisive place and have people look at it and think a war-zone image of the border. I imagine by now we’ve already spent more time sending the military to the border than what it would have cost to put a new port of entry in Douglas.”

The Arizona Daily Star reported in 2017 that a price tag to renovate the existing Douglas port of entry and build a new commercial entrance wasn’t known, but it had cost nearly $200 million to renovate the Mariposa Port of Entry in Nogales.

As the Nogales International first reported, the razor wire around Nogales now extends outside the city limits to the Kino Springs area, where the tall pedestrian fence gives way to a waist-high Normandy-style fence meant to stop vehicles. In a photograph published by the Nogales newspaper, the razor wire is seen lining the steel bollards and suddenly ending as the vehicle barrier begins, where people on foot can easily cross.

The military has also spent resources fixing the wire. Right by the Morley Gate, they’ve had to at least twice remove a piece of carpet thrown on top of the razor wire, presumably to make it easier and safer to jump from the fence. Downtown store employees showed the Star pictures of troops working to carefully disentangle the rug from the fence.

During a House Armed Services Committee hearing on Jan. 29, chairman Adam Smith, D-Wash., said the deployment of active-duty service members, while not unprecedented, was highly unusual.

“If you look at the statistics, the peak of our problem at the border was in 2004 and 2005,” he said, when there were more than a million apprehensions compared to the 400,000 or less in recent years.

While members of the caravans by and large have not made their way here, Border Patrol agents in the Yuma and Tucson sectors continue to apprehend groups of more than 100 Central Americans traveling as families.

DOD and CBP have said the military presence has allowed Customs officers and Border Patrol agents to be able to focus on the most pressing needs and more clearly spot vulnerable areas.

It has given CBP the ability “to spread their power more easily,” Navy Vice Admiral Michael Gilday, director of operations for the Pentagon’s Joint Staff, told Smith in response to a question about what metrics for success they were using.

“The fact that we hardened those ports of entry, that’s probably the best answer I can give you,” he said. He later added that it would be like trying to prove a negative “if we are trying to prove how many people didn’t cross the border. The fact is CBP was better-prepared because of the work we did.”

And as they transition to the new mission from the ports of entry to the areas between the ports, Gilday said, the troops bring a skill set — surveillance and detection — that will be particularly beneficial.

Shoppers walk along North Morley Avenue in Nogales. Residents and business owners complain about long wait times to cross the border, sometimes exceeding two hours, which they say harms businesses and the quality of life.

Border voices

For some, though, it is one more symbol of how misunderstood border communities are.

“Although the razor wire is the most aggressive action so far — and a publicity stunt, no doubt — the situation on the border has been escalating for years,” Kory said.

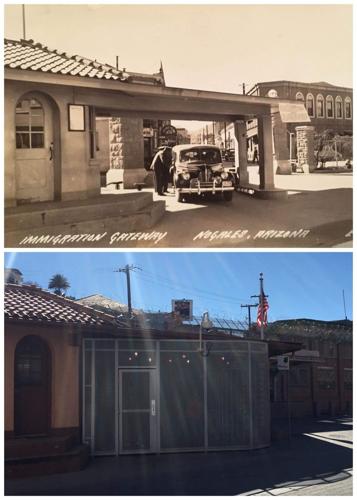

He points to a postcard from 1941 of the Morley Gate, across from his parents’ business, that shows an open space that’s now been surrounded by a dense fence that he calls a cage. He sees it as proof of how much more unwelcoming the environment is.

This 1940s photo of the Morley Gate at the U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales shows an open crossing. Evan Kory, who family has owned businesses in downtown Nogales for many decades, says he's notice the change of how the border has become less welcoming for residents on both sides.

“You hear on the news that an invasion is coming, but in fact,” he said, “border communities have been invaded by our own government.

“Our surroundings were invaded before anything happened that they were saying was going to happen.”

“We have between 1,600 to 2,000 trucks a day, depends on peak times; thousands of vehicles and pedestrians coming through our ports legally,” Garino, the mayor, said. “Why not concentrate on that? On those trade opportunities, economic development for our state and for the country.”

Resident and business owners complain about long wait times to cross the border, sometimes exceeding two hours, which they said harms businesses and quality of life.

Average peak times at the DeConcini Port of Entry, for instance, show an increase from 77 minutes in December, fiscal year 2018, to 97 minutes in fiscal year 2019. Of Arizona’s major land ports of entry, only San Luis exceeded an average peak time of two hours, CBP data show.

The image of fear makes it harder on border communities that are trying to attract people and jobs, the residents say.

Even one of Adams’ colleagues, who works with a binational ministry creating relationships across borders, doesn’t want to cross anymore.

“The psychological impact is tough,” he said.

Said Garino: “They look at things differently in Washington, and half of those people have never been to the border.”

“We have good access roads in this area, surveillance, technology,” he said. “Per capita, we have more law enforcement officers in this city and county than almost any other county in the state.”

His concern is that even if Congress and President Trump agree on border security and there are no caravans, the wire will remain.

“If everything is working, going in a positive direction, is it still going to be up there?”

Arturo Garino, mayor of Nogales, Arizona, says 16 businesses on Morley Avenue have closed in the last four years. He urged Sen. Martha McSally to have the border razor wire removed.