It’s been a decades-long process, but construction of Downtown Links is now — relatively speaking — on the horizon.

Project manager Sherry Martin of the Tucson Transportation Department said the city has already put out a request for qualifications for a company to oversee construction. A request for construction bids will likely come toward the end of the year, and actual dirt-turning “would theoretically be three months after that,” Martin said.

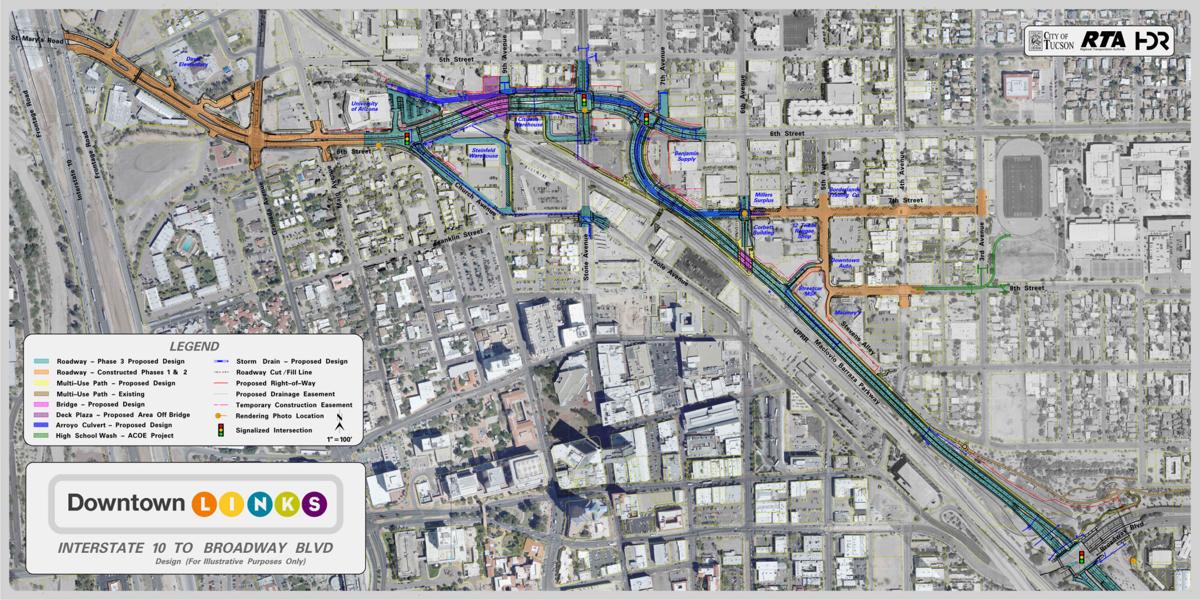

At the end of the estimated two-year construction time for the third and final phase of the roughly $96 million, RTA-funded project, a new four-lane road will take drivers from the Barraza-Aviation Parkway near the snake bridge to Interstate 10 and bypass the often-congested downtown area. There will also be new multi-use paths, upgraded railroad crossings and improved drainage infrastructure, which could make submerged cars in the downtown underpasses during the monsoon a thing of the past.

“It provides alternative access to and through downtown, that’s really the reason why we’re building it,” said Tom Fisher, who was the previous project manager.

As it stands, roughly 70 percent of the vehicles in the downtown area are simply passing through on their way to somewhere else, according to fairly recent traffic studies.

Once it’s complete, Eugene Caywood, who was chair of the project’s citizens advisory committee and whose involvement stretches back to the popular opposition to the Arizona Department of Transportation’s first proposal for the connection in the 1980s, said the situation for downtown motorists and pedestrians will be much improved.

“It’s gonna free up the flow along Congress Street, which makes it easier for pedestrians, and should relieve some of the pressure” at the Fourth Avenue underpass, he said.

Sky Jacobs, a Dunbar Spring resident and former president of its neighborhood association, was more skeptical of the scale of those benefits, given that the four-lane plan is a “scaled-back” version of the eight-lane ADOT proposal, and will still have to contend with traffic lights. The speed limit will be 30 mph.

“It’s really not too much different than it is now,” he said, adding later that the project has also come at the cost of a number of historic buildings in the area.

As Caywood knows as well as anyone, it has been a long and often-contentious path to get to the cusp of construction. With the help of Caywood and numerous other opponents, who were concerned with the number of impacted properties and limited access along the route, ADOT’s original plan was shot down in the late 1980s and Tucson took it over. Since then, more than 20 different routes have been considered before the final one was selected.

Caywood concedes the final plan still has its critics, especially in the Dunbar Spring neighborhood, which will lose vehicle access to downtown on Ninth Avenue. To address some of those concerns, Fisher said a park will be constructed over the Sixth Street underpass deck, along with the bike and pedestrian paths already planned, “to try to maintain the sense of community in that area.”

Jacobs said that concession was the fruit of neighborhood organizing and that if not for residents having “fought hard,” it wouldn’t have been granted. While skeptical of the project in general, he and others are looking forward to the improved bike and pedestrian connectivity that comes with it.

Given planned improvements at a number of railroad crossings, Dunbar Spring residents are also hopeful that they might get a break from the piercing train whistles that are, for the time being, a part of life in the neighborhood.

“TDOT has said they will do what needs to be done” to get to whistle-free crossings, current neighborhood association President Karen Greene said.

“You could say (Dunbar Spring) got the short end of the stick, but I think there was broad enough community consensus to overcome their objections,” Caywood said, adding, “We worked hard to disrupt them to the least possible with a roadway of this scale.”

There was also a fair amount of disagreement in the right-of-way acquisition phase of the project, which is now largely concluded. While the City Council generally gives blanket authorization to use eminent domain prior to major road projects, the city doesn’t often have to turn to the courts. Jim Rossi, head of transportation’s real estate division, estimated there are court filings to obtain the properties in 10 to 20 percent of cases.

However, the city had to take legal action on 10 of the 19 properties it had to partially or completely acquire for Downtown Links, though most have been settled, according to a document provided to the Road Runner through a public-records request. There are another 14 parcels previously acquired by the state for the project prior to the city taking it over that are being used as well.

“Whenever there is a large dispute, or a large number of disputes ... it indicates that there was some major disagreement between the government agency and the private property owner regarding the value of the property taken,” said Carl Sammartino, an attorney who represented several of the affected owners.

Though they were on opposite sides of those disputes, Rossi and Sammartino agreed on the principal cause for the disagreements: The boom in downtown development, which led many owners to believe that their properties were worth more than the city was offering. A quick review of the offer and ultimate settlement figures shows that owners ended up with about 60 percent more than what was originally on the table, according to court documents.

That did mean spending hundreds of thousands of dollars more on acquisitions than the city had planned, but Fisher and Martin said that it has not significantly impacted the project.

“You can reduce the scope, or you can go find more money,” Fisher said of the impact. “We’ve chosen to go find more money.”