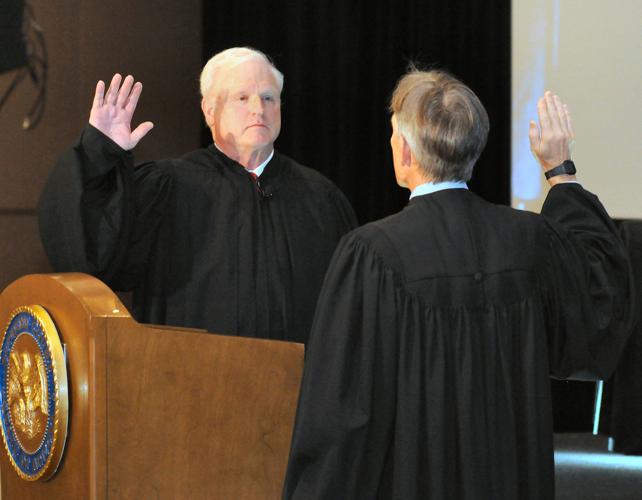

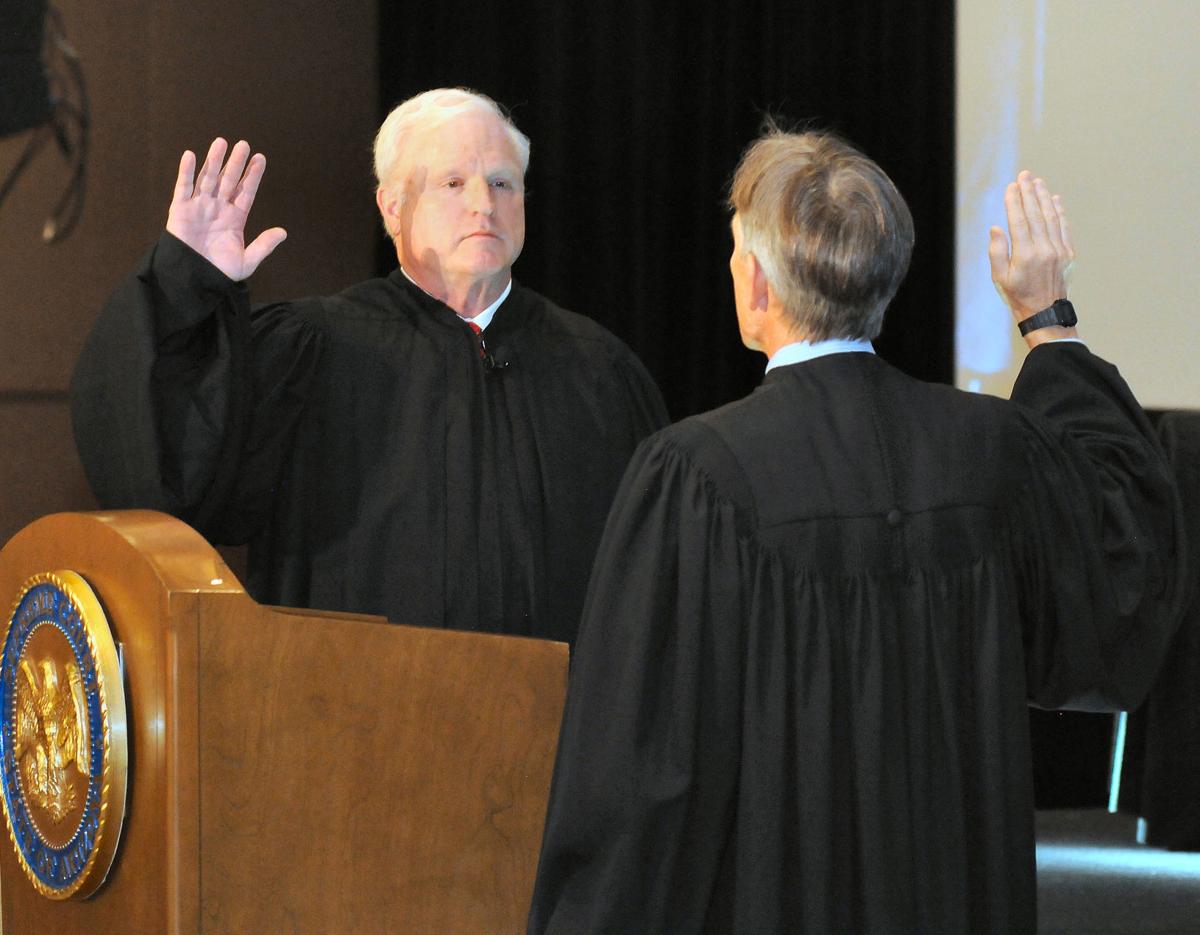

PHOENIX — Anyone looking for major changes at the Arizona Supreme Court with the naming Friday of Robert Brutinel as its chief justice is likely to be disappointed.

Yes, Brutinel is a Republican. And he is replacing Democrat Scott Bales, who is retiring from the court.

And Brutinel, who served on the Supreme Court for nine years — and 14 years before that as a Yavapai County Superior Court judge — does have some priorities he hopes to accomplish in his five-year term. That includes finding better ways for the legal system to handle the mentally ill rather than having them wind up in jail.

But major changes?

“You know, I don’t know it’s going to be different at all,” the new chief justice told Capitol Media Services.

Some of that is, quite simply, that the Arizona Supreme Court is nothing like the U.S. Supreme Court — and not just because the governor, unlike the president, is restricted to making appointments from a pre-screened list versus whoever he or she wants. That federal system has produced what is pretty much universally considered an ideologically divided high court, with often-predictable votes by the liberal and conservative justices.

Brutinel said while judges have partisan backgrounds, as many actually ran for office, that politics does not carry over onto the bench here in Arizona.

“I don’t know that I’ve ever had an ideological discussion with one of my colleagues about a case,” he said.

“That’s not how we view it,” Brutinel said. “We apply the law.”

What that also means, he said, are few split decisions — certainly fewer than emerge from Washington.

“We still try very hard to be unanimous in cases when we can be,” Brutinel explained. That, he said, is often accomplished by trying to decide cases “very narrowly” to resolve the specific lawsuit rather than look for excuses to take on broader legal philosophical issues.

And having unanimous decisions, said Brutinel, has another benefit.

“We do that to provide certainty in the law,” he said.

Beyond the question of cases before the court, Brutinel does say that he, like every other chief justice, has crafted a new “strategic plan” for what he hopes to accomplish at all the courts in the state, right down to justice courts, all of which are under the control of the Supreme Court. But here, too, don’t look for radical new ideas.

“It continues a lot of the things that Scott started,” he said.

One of those is “bail reform.”

“What we want to do is make release determinations based on risk and not on your ability to pay,” Brutinel said. “We don’t want people remaining in jail only because they can’t afford the bond.”

What already has happened, he said, is the courts have created “risk-analysis instruments” to help judges determine who can be released. What’s next, said Brutinel, is automating that system to make it available — and more quickly — to all levels of the court system.

“We want dangerous people to stay in jail, people who are a risk to the public,” he said. “But we want people who are safe to release to be out working their jobs and being with their families.”

For his own agenda, Brutinel wants to focus more on the question of mental health.

“The idea (is) that we will find ways to get mentally ill people out of the jails and out of the emergency rooms and out of the justice system and into treatment every opportunity we can, so that the mental health system doesn’t reside in the jails; it resides where it ought to be.”

Brutinel wants to expand those programs throughout the state. And he said that helps not only those with mental health problems but also makes the criminal justice system more efficient in being able to deal with those who should get the attention of the courts.

One thing that may be different is under Brutinel is that he wants to shift away a bit from the practice of the last two or three decades of promoting arbitration to resolve civil disputes instead of going to court.

“I think courts and trials are an efficient means of resolving disputes,” he said. “I think we should get back in the business of trying cases.”

Brutinel acknowledged the other side of that equation is that courts are going to “have to get more efficient” at resolving cases. But he said it’s not impossible.

For example, he cited FASTAR, a pilot in Pima County which stands for the fast Trial and Alternative Resolution Program. He said that can work well for cases where the amount of the dispute is less than $50,000, with limited pretrial “discovery,” the exchange of information between the attorneys.

Those, said Brutinel, are the cases currently being pushed into arbitration. He said putting these back in court “can get lawyers back in the business, particularly young lawyers who are learning how to try cases.”

“We’re resolving cases just as quickly,” Brutinel said.

And there’s something else.

“The primary difference from my perspective is if you’re not happy with the result, unlike arbitration, you can appeal,” he said.

Beyond that, Brutinel said having more jury trials is not just an efficient means of resolving disputes but also is important for civic reasons.

“I think people may learn about their government by participating in it,” he said. “And jury service and voting are really the two ways the average person gets to do that.”

Brutinel also said it may be time for voters to reconsider a constitutional provision that requires all judges to retire at age 70.

“Mandatory retirement ... probably made sense at the time of statehood,” he said. “I don’t think it makes sense now.”

Brutinel, who is 61, declined to say what is the appropriate age. But he said he’s not looking to change things for himself.