PHOENIX — A Sedona resident will get his chance to prove state utility regulators illegally withheld information about a study of the health effects of “smart” meters.

In a ruling Tuesday, the state Court of Appeals said Warren Woodward is entitled to have a judge determine whether the Arizona Corporation Commission acted improperly in refusing to disclose some details.

Attorneys for the regulators claimed a variety of reasons for denying access to documents, including that some would disclose the “state of mind” of those writing it.

Judge Diane Johnsen, writing for the unanimous three-judge panel, said Woodward may be legally entitled to share what he already knows of the information he was initially denied, information a trial judge told him he had to keep to himself.

That could undermine public confidence in the commission’s decision to allow utilities to effectively force the radio-transmitting electric meters onto their customers.

According to court documents, Woodward found evidence that commission staffers may have had input into what was supposed to be an independent investigation by the Department of Health Services into whether the meters — and the radio emissions they make — can affect residents of the homes where they are installed.

Woodward said he also has other evidence the health department study may have been skewed because of commission influence.

“ACC had their fingerprints all over this study from beginning to end,” he said, saying commission staffers provided the health department with studies claiming the meters are safe “and said, basically, in so many words, this is what we’re looking for.”

Commission spokeswoman Holly Ward declined to discuss any of the specifics. She said her agency will await some direction from the Yavapai County Superior Court judge who now gets to decide what more Woodward can make public and whether the commission acted illegally in keeping information from him in the first place.

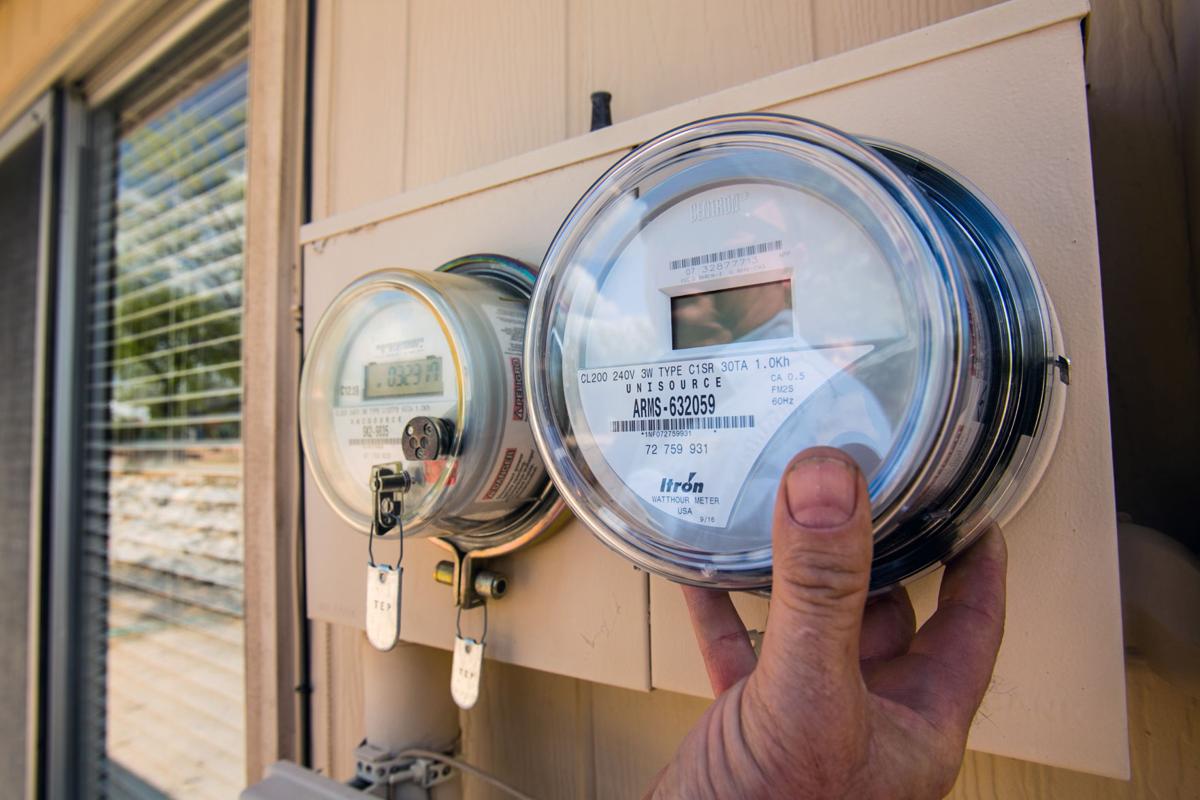

“Smart” meters provide a utility with regular updates via radio signals of each customer’s usage.

Most major electric companies use them as an alternative to having staffers go out and physically read meters. In fact, the commission has said utilities can charge an additional monthly fee to customers who have health concerns and want to opt out of the smart meters.

In a 2014 study done for the commission, the health department found there are studies that show radio frequencies might affect human physiology.

“However, these studies cannot conclude that the cellular changes necessarily lead to disease,” the report says.

Separate testing to determine the maximum exposure someone might get from a meter in a “worst-case scenario” concluded that the levels of radio frequencies were below “levels of public health concern.”

“With the available information, exposure to (smart) meters are not likely to harm the health of the public,” the report concluded.

Woodward then sought records on the study, including communications among commissioners, staffers and the health department. Some of what the commission provided him had multiple words, sentences and, in some cases, even pages blacked out.

When he filed suit, Jeffrey Paupore, an acting judge in Yavapai County, decided to review the undredacted version of the records. He also gave a copy to Woodward so he could make his arguments about why he was entitled to the information.

Paupore eventually ruled that since Woodward got the information, the lawsuit was moot — though he barred Woodward from distributing what he had.

Johnsen, in Tuesday’s ruling, said Paupore should not have issued such a blanket restraining order.

“A prior restraint is the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights,” she wrote. She said Paupore made no findings to support his order.

Tuesday’s ruling now requires Paupore to consider both whether the commission improperly withheld public documents in the first place — a finding that could force the commission to pay all of Woodward’s out-of-pocket costs — as well as the validity of the gag order.

In the meantime, through his court filings, Woodward already has made public some of what he got.

For example, the commission refused to disclose one email thread as “attorney-client privilege.”

But Woodward said it turns out that it was about setting up a meeting between commission staffers and the health department to review the study the commission had asked be performed.

“This is an opportunity for us to look at the DHS report before it is sent over to the ACC,” wrote Jodi Jerich, then the commission’s executive director. Woodward also claims the commission, which was supposedly looking for an impartial report on the meters, was “looking for studies to whitewash the effects of the smart meters” and sending them to the health department.

He said the commission, having sought the health study, should have taken a “hands-off” approach. “That’s not what happened,” Woodward said.

The redactions also hid the fact that some of the health department study was done at the home of the commission’s chief engineer.

Woodward also found an email from then-Commissioner Brenda Burns to a staffer was completely blacked out under the claim of “state of mind.” He said it turns out that Burns wanted the staffer to “give me some quotes” so she could make comments at an upcoming meeting.

Commission attorney Andy Kvesic on Tuesday defended the exclusion based on “state of mind,” saying that’s just a different way of concluding that commissioners and their staffs are entitled to a “legislative privilege” to shield communications that are part of reaching a decision.