Kendrick Pittman was a lonely, incarcerated teen 17 years ago when a retired Army colonel started visiting him at Tucson’s now-closed Catalina Mountain School.

Pittman, then 15, assumed this new mentor would eventually abandon him, just as other adults had.

Instead, George Sallaberry saw Pittman regularly for several hours each week, remaining steadfast through his angry outbursts and his grief.

During those 18 months, Sallaberry opened Pittman’s mind to the broader world by sharing stories and photos of overseas trips he’d taken.

And Pittman, thanks to Sallaberry’s math tutoring, advanced from being a failing student to eventually passing his high school equivalency exam.

He says he believes Sallaberry was God-sent to save his life — and on Thursday, he paid it back.

Sallaberry, 74, had stage 4 kidney disease and, as it recently progressed, his options were to start dialysis or get a kidney transplant.

The two men have stayed close through the years, talking on the phone twice a week and often meeting for lunch.

When Sallaberry needed a kidney to save him from dialysis, Pittman, a 32-year-old truck driver and father of two, immediately volunteered for a blood draw.

‘Didn’t know how to be healthy’

Sallaberry, a SaddleBrooke resident, retired as a full colonel in the U.S. Army after 27 years of service.

He started volunteering at Catalina Mountain School a couple years later, an undertaking he sought “after a few years of golf and self-indulgence.”

The school, at 14500 N. Oracle Road before closing in 2017, was the oldest of the state’s several juvenile corrections centers.

Pittman was there about 18 months, a place he landed after a chaotic, traumatic childhood. He had been abandoned at an orphanage before he turned 10, and he lost a brother in his teens.

He’s since forgiven his parents, he said, and has a relationship with both now.

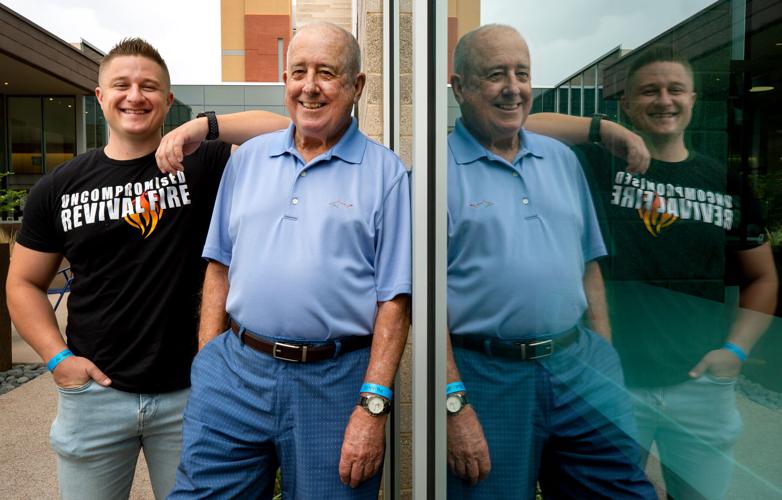

Kidney donor Kendrick Pittman, left, and recipient George Sallaberry at Banner-University Medical Center. Thursday’s surgery went well, and both patients were expected to go home this weekend.

“They didn’t know how to be healthy themselves and so they couldn’t model it for us,” he said, referring to himself and his five siblings.

Pittman’s early years included many problems with authority and, right before he landed at Catalina Mountain, a probationary period he did not take seriously.

In hindsight, Pittman says, he got into trouble a lot as he aged because he was “always trying to find out where the boundary was” from the adults in his life.

Sallaberry, with his decades of military leadership, was quickly able to gauge this about Pittman and help him progress.

“He had a lot of anger,” Sallaberry said, “and he was a perpetual victim.”

Pittman was released from Catalina Mountain six months before his 18th birthday and went to live in a group home.

Sallaberry said he was warned not to stay in touch, and especially to not give Pittman his phone number or address.

He didn’t heed the advice, and instead kept right on visiting Pittman at the group home.

“I wasn’t worried about Kendrick,” he said.

Pittman said those visits were critically important: he was very lonely, and knowing Sallaberry cared and could be relied upon made all the difference.

Surgeon Dr. Suzi Klau speaks with kidney donor Kendrick Pittman before Pittman’s surgery Thursday at Banner-University Medical Center in Tucson.

‘I’m doing it’

On Thursday morning, the friends arrived at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson so Pittman could donate one of his kidneys to Sallaberry.

Everything went well and, on Friday afternoon, the pair were recovering, said hospital spokeswoman Rebecca Ruiz Hudman.

“They are doing fantastic,” she said.

Pittman was likely to go home Saturday, she said, and Sallaberry on Sunday.

At first, weeks back, Sallaberry tried to discourage Pittman from the surgery, saying he could see if a family member might be able to do it instead.

Pittman wouldn’t hear of it.

“I told him, ‘It’s already done. If I’m a match, I’m doing it,’ “ he said. “How could I not give back to him?”

Matches are more common between close relatives due to compatibility of blood type, and many other factors.

But these two turned out to be an almost perfect match.

Sallaberry laughed happily as they recalled the story earlier last week.

“His line was like, ‘You saved me, now I’m going to save you.’”

Photos: Man donates a kidney to his mentor

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry

Updated

Kidney donor Kendrick Pittman, left, with recipient George Sallaberry at Banner University Medical Center.

George Sallaberry

Updated

Dr. Venkatesh Ariyamuthu examines George Sallaberry, 74, at Banner - University Medicine North. Sallaberry suffers from stage 4 kidney disease.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

George Sallaberry, donor recipient, winces while getting an IV before his kidney transplant surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Dr. Robert Harland, transplant surgeon, explains the kidney transplant surgery to George Sallaberry at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Debra Ralph gives her son, Kendrick Pittman, a kiss before Pittman's kidney surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Dr. Suzi Klau, surgeon, speaks with kidney donor Kendrick Pittman before Pittman's surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Donor recipient George Sallaberry rests his hands on his chest while waiting to be taken into surgery for his kidney transplant at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Donor recipient George Sallaberry walks to his pre-op room before his kidney surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Dr. Alexandra Turner, left, donor surgeon, talks with Kendrick Pittman, kidney donor, before Pittman's kidney surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Shannon Connolly, RN, writes on a white board while prepping Kendrick Pittman for kidney surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Kidney donor Kendrick Pittman is wheeled out of his pre-op room into surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Donor recipient George Sallaberry looks over some last minute paper work before heading into his kidney transplant surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.

Kendrick Pittman and George Sallaberry getting prepped for surgery

Updated

Donor recipient George Sallaberry is being wheeled to his kidney transplant surgery at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson.