PHOENIX — Arizonans likely won’t get to decide this year whether they want to ban anonymous contributions to political campaigns.

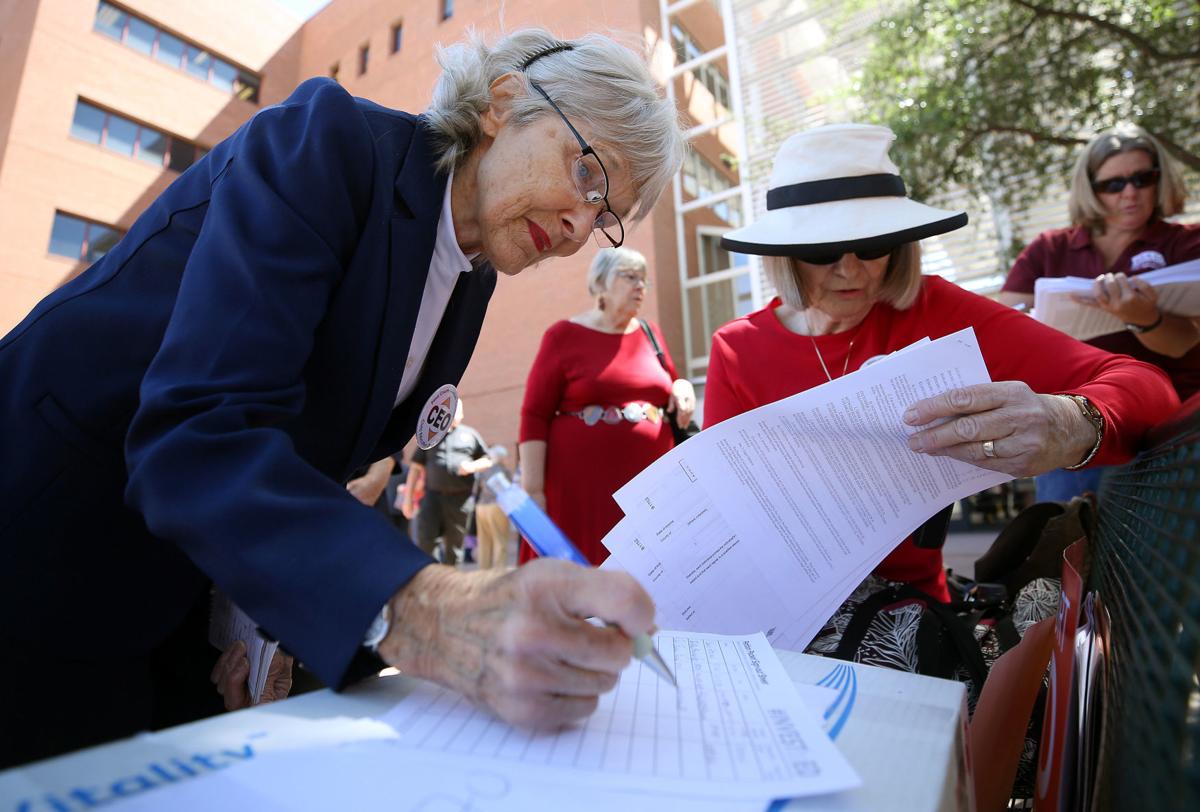

Organizers of the initiative campaign announced Thursday they are suspending efforts to gather signatures to put the issue on the November ballot.

This comes amid public-health calls to minimize person-to-person contact, such as the contact necessary when circulators approach people to sign petitions.

Terry Goddard, co-chair of the “Citizens Right to Know” or “Outlaw Dirty Money” initiative, said that, as of Thursday, after a year of being on the streets with petitions, they were about 81,000 names short of the 356,467 valid signatures needed to qualify for the ballot.

But Goddard said they were still on track to meet the July 2 deadline, with a contract for paid circulators and 300 volunteers who he said were ready to go out earlier this month during the presidential preference election to gather signatures.

The initiative would create a “right to know” provision in the Arizona Constitution requiring public disclosure of the name and address of any individual who has put at least $5,000 into influencing the outcome of any election, whether directly or indirectly.

It would apply not just to donations directly to candidates, which essentially already are covered, but also donations to political action committees which then make their own contributions to candidates solely in the name of the group.

The more significant provision applies to so-called “social welfare groups” that now can spend unlimited amounts of money on TV ads, mailers, billboards and phone calls both for and against candidates as well in supporting and opposing ballot measures. That would override a law approved by the Republican-controlled Legislature exempting those groups from having to disclose their donors.

The initiative is unlikely to be the only one endangered by the reticence to seek person-to-person signatures.

Backers of a measure to impose new minimum-wage requirements for hospital workers and to require insurers to cover preexisting conditions paused their own petition circulation campaign earlier this month.

And signature gathering has been halted by a group seeking changes in election laws, including automatic voter registration and tightening the limits on what lobbyists can give in gifts to public officials.

Not every ballot measure is in trouble.

The Smart and Safe Arizona initiative to legalize the recreational use of marijuana by adults already collected more than 320,000 signatures, with just 237,645 of those required to be found valid, said Stacy Pearson. She is vice president of Strategies 360, which is helping run the campaign.

Less clear, Pearson said, is the fate of two other ballot measures being handled by her firm.

“We’re actually experimenting with some options to find the best way to both legally and safely collect,” Pearson said. She said that might involve taking petitions to someone’s house, then stepping back and letting them sign with their own pen.

Any procedure would have to comply with an Arizona law that requires those who circulate petitions to sign affidavits saying they witnessed the signature.

Goddard said there is a way to salvage not only his initiative but others that have been sidelined by COVID-19: Have the Legislature allow signatures to be gathered online.

“It’s just basic fairness,” he said, pointing out that state lawmakers voted to allow themselves to gather signatures for nominating petitions electronically. To date, however, no bill to expand that has ever gotten a hearing.

“We’ve got a situation here where they treat themselves royally with access to electronic signatures. But they don’t let anybody else have it. I think that’s fundamentally unfair and perhaps illegal,” said Goddard, who is a former Arizona attorney general.

The other alternative, he said, would be to allow any signatures gathered for this election cycle to be held over and used to put the issue on the 2022 ballot. That, too, is currently illegal, as the law prohibits signature gathering before the last election results have been announced.

Goddard said lawmakers should be willing to consider either measure, “especially when you have a crisis like this and you’re basically prohibited by circumstance from using person-to-person contacts.”

He said, though, the preferable choice would be to allow the same kind of electronic signatures on initiative petitions that are permitted for candidates.

“It’s perfectly valid,” he said. “It makes sure that you have a registered voter signing. It meets all the anti-fraud provisions.”