Click on the image below to scroll through the interactive map. If reading on the Tucson.com app, tap here to open the map in a browser.

Federal officials are diverting $1.2 billion in anti-narcotics funds to build a border wall across marijuana smuggling routes to Arizona — although marijuana seizures at the border already are plummeting without it.

At the same time, smugglers are moving ever larger loads of the more dangerous and illegal drug methamphetamine through ports of entry where the wall can't stop them.

And the 30-foot wall is going up even though marijuana is grown and sold legally for medicine on the Arizona side of the wall, and for recreation in California and other states.

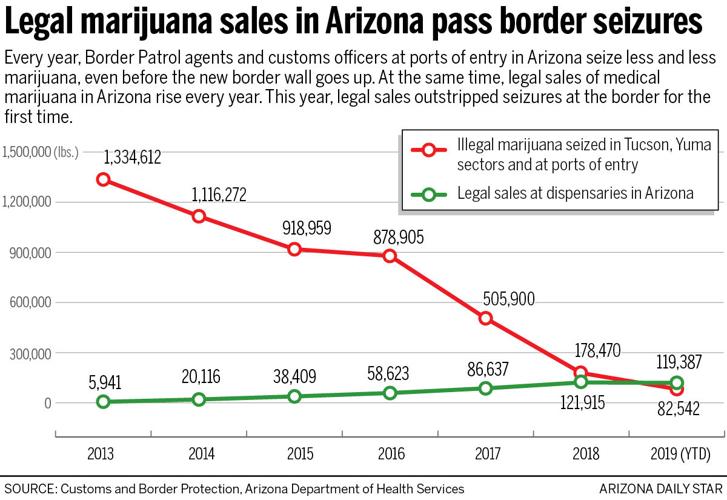

For the first time, in fact, sales of medical marijuana in Arizona this year surpassed the amount of marijuana seized at the state's border with Mexico.

The Department of Homeland Security's request to divert the anti-narcotics funds to build the wall bore only a vague resemblance to how drug smuggling works in Southern Arizona, an Arizona Daily Star analysis of about 750 federal drug-smuggling cases shows. The Star investigation provides a rare view of drug-smuggling routes and how they are used.

Workers pour a foundation for the installation of border wall panels about 3 miles east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry.

Between the walls

Wall construction so far in Southern Arizona is centered on Lukeville, a small border town about 150 miles southwest of Tucson. Since work started in late August, crews have built more than 1,200 feet of wall east of Lukeville.

Similar work could start soon on the west side of Lukeville, where crews are clearing the area near the border and stacking materials to build the wall.

In between the two wall-building projects, a line of cars and pickup trucks in Sonoyta, Mexico, inched toward the Lukeville port of entry on a recent afternoon, just as more than 1 million people did last year.

The line was full of drivers heading back to the United States from the beaches of Rocky Point, Sonora, visiting friends and family, or any number of legitimate reasons. Across the border at the gas station in Lukeville, children in goofy T-shirts asked travel-weary parents to buy them snacks amid bathroom breaks and gassing up the car. Other travelers got through customs and headed north toward the town of Why and Arizona 86, which becomes Ajo Way into Tucson.

Vehicle lines like these are where most hard drugs such as meth and cocaine are smuggled across the Arizona-Mexico border, according to the Star's review of hundreds of court cases filed from Yuma to Douglas in 2018.

Hard narcotics, which are far more valuable per pound than marijuana, are sent through ports so they can "blend with legitimate traffic," said Scott Brown, special agent in charge of the Phoenix office of Homeland Security Investigations.

When smugglers cross in the desert, "there is no legitimate reason to do that so you're going to draw increased scrutiny," Brown said.

Click image to enlarge graphic

Despite being the site of most hard drug seizures, the ports are not where the $1.2 billion in anti-drug smuggling funds will be spent. Instead, that money will fund a wall that cuts a line through the path of marijuana smugglers and migrants crossing the border through the desert, court records show.

In February, President Trump declared a national emergency at the border after Congress refused to set aside more money for the border wall. Ten days later, Homeland Security sent the Pentagon a request for counter-narcotics funds, including $1.2 billion for 63 miles of wall in Arizona near Lukeville and Douglas.

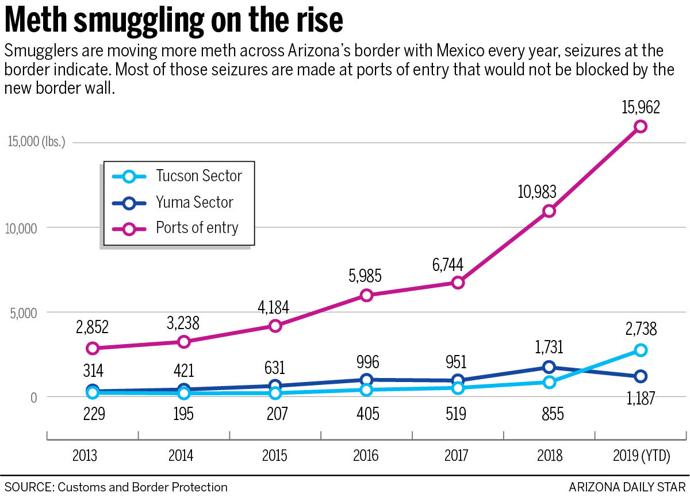

The decision by DHS to ask for anti-narcotics funds came as meth seizures at ports of entry along the Arizona-Mexico border jumped from 2,800 pounds in fiscal 2013 to 16,000 pounds in the first 11 months of fiscal 2019. That's a 460% increase.

The Border Patrol also saw an increase in meth seizures on highways in Southern Arizona, although on a smaller scale. Agents seized 540 pounds of meth in fiscal 2013 and 3,900 pounds so far in fiscal 2019, according to Customs and Border Protection data.

Meanwhile, marijuana seizures in Southern Arizona plunged from 1.3 million pounds in 2013 to 83,000 pounds in the first 11 months of fiscal 2019 — a 94% drop.

Border Patrol agents seized more than 26,000 pounds of marijuana in the west desert region of Arizona that includes the area around Lukeville, the Tohono O’odham Nation and Sasabe in 2018, according to a Star analysis.

For the first time since medical marijuana was legalized in Arizona in 2010, legal sales are outstripping seizures of marijuana at the border, with about 120,000 pounds sold legally from January to September, Arizona Department of Health Services data show.

The pattern that emerges when analyzing drug-smuggling cases in Southern Arizona is hard to miss: Marijuana backpackers are busted in the desert, while smugglers bring hard narcotics through ports of entry hidden in vehicles or strapped under their clothes.

"That is 100 percent correct," Brown said when asked about the pattern. "The vast majority of hard narcotics are encountered at ports of entry; the vast majority of marijuana is encountered between ports of entry."

The public affairs office for CBP did not respond to inquiries from the Star, but a Border Patrol agent in Yuma wrote in a Dec. 7, 2017, criminal complaint that the "main narcotic smuggled by drug trafficking organizations operating in the Arizona desert is marijuana."

“While there are loads of hard narcotics — to include cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin — marijuana accounts for over 98% of the narcotics seized in the desert,” the agent wrote.

The longstanding pattern of marijuana going through the desert and hard drugs going through ports of entry has been reported by federal agencies and numerous news outlets, including the Star. But those reports only show a general view of how drug smuggling works, due partly to CBP's reluctance to share detailed information.

Click image to enlarge graphic

Court records, on the other hand, show the cities, towns, highways, checkpoints and ports of entry where drugs are caught, as well as the quantities and how they were smuggled.

The Star's analysis identifies four major smuggling corridors in Arizona: the Yuma area; the west desert area that includes Lukeville, the Tohono O'odham Nation and Sasabe; the area around Interstate 19, which runs from Nogales to Tucson; and the Cochise County area in the state's southeastern corner.

Sprinkled among the Lukeville travelers last year were a few dozen drivers smuggling a total of 1,100 pounds of meth, nearly nine times the amount Border Patrol agents seized in the west desert smuggling corridor that surrounds Lukeville, court records show.

In a typical case at the Lukeville port, a 19-year-old U.S. citizen was driving her Hyundai Santa Fe SUV from Rocky Point to her home in Tucson on June 11, 2018. She appeared nervous to a customs officer. An X-ray scan of her car showed anomalies inside the front and back seats and in the windshield wiper area. Officers searched those areas and found nearly 47 pounds of meth.

She told officers she had gone to Rocky Point to celebrate her friend's birthday, a friend that prosecutors said recruited drivers through Snapchat and got out of the car right before they entered the port of entry.

In a typical case in rural areas near Lukeville, a Border Patrol agent spotted several people wearing camouflage and carrying backpacks on the side of a road on Feb. 10, 2018. The agent told them to stop, but they dropped their backpacks and scattered. Agents caught five of them and seized more than 200 pounds of marijuana.

One of the men said he had agreed to pay $2,000 to be smuggled into the United States. He later agreed to carry a backpack of food in exchange for having his smuggling fee waived after one member of the group turned back to Mexico. Another man in the group said he was going to be paid $1,800 to take marijuana to Phoenix, after which he was going to return to Mexico.

That marijuana was a small portion of the 26,200 pounds Border Patrol agents seized in the west desert in 2018, court records show, compared with 2,200 pounds seized at the Lukeville port.

The pattern has its exceptions, including two recent busts that raised alarm bells with the Border Patrol.

The Tucson Sector sent out a pair of news releases in July and August about backpackers who were caught with meth about 30 miles east of Lukeville, which would put the seizures on the Tohono O'odham Nation where no new wall will be built.

"There is growing concern in the Tucson Sector Border Patrol that the routes and tactics smuggling organizations historically used for marijuana are being converted to hard narcotics," Border Patrol Agent Pete Bidegain said.

The cases were turned over to Homeland Security Investigations. Brown said he has seen a handful of such cases, but "it's a drop in the bucket" compared with meth seized at ports of entry.

Nowhere is the traditional smuggling pattern more pronounced than in the smuggling corridor that extends along Interstate 19 from Nogales, which has had an 18-foot tall border fence downtown and taller fence outside of town since 2011 and is not slated to get any new wall.

A customs officer checks a vehicle at the downtown port of entry in Nogales, Arizona. Ports like this are the most common route for smugglers to bring meth, heroin and fentanyl into the U.S.

People walked or drove through Nogales ports into the United States more than 10 million times in 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

On a recent afternoon, school children were walking home to Nogales, Sonora, after a day of classes in Nogales, Arizona. Mexican shoppers milled around in front of the stores that line Grand Avenue, which connects the downtown port of entry to Interstate 19, and cars went back and forth from the port.

Customs officers seized 5,300 pounds of meth at Nogales ports in 2018, court records show. Border Patrol agents seized another 350 pounds at the I-19 checkpoint in Amado, about 30 miles north of Nogales, and another 100 pounds from vehicle stops on highways.

In a typical case at the Nogales ports, a man drove a Chevrolet Equinox SUV from Mexico into the downtown port of entry. He avoided eye contact with a customs officer. An X-ray scan showed anomalies in the SUV's rear quarter panels, both rear doors, and the front passenger door. A drug-sniffing dog then alerted to those areas of the SUV.

Officers found 60 pounds of meth stashed in the SUV. The man told officers he did not know about the meth, but WhatsApp audio messages on his phone included instructions on where to park his vehicle in Nogales, Sonora, and to leave the keys under the driver's floor mat, a common practice among smugglers.

In a typical case at the I-19 checkpoint, a Border Patrol canine alerted to the rear of a sedan with an Arizona plate on Feb. 7, 2018. Agents found a panel hidden above the muffler that opened into a contrived compartment. Agents found nine brown, taped packages of cocaine that weighed about 25 pounds.

The driver said she would get paid $350 each time she drove a vehicle from Mexico to the Arizona Mills Mall in Tempe, where she would leave the vehicle unattended with the keys inside before driving back to Nogales, Mexico.

Northbound commercial truck traffic lined up for inspection at the Mariposa Port of Entry in Nogales, Arizona. Customs officers seized 5,300 pounds of meth at Nogales ports in 2018.

A $1.2 billion letter

The Feb. 25 request by DHS to divert more than $1 billion of the Pentagon's anti-narcotics funds to build the wall included several striking errors and omissions.

The pattern of hard drugs going through ports and marijuana going through the desert where the wall would be built was nowhere to be found in DHS's request.

Instead, DHS drastically understated the amount of marijuana seized in the Border Patrol's Tucson Sector in fiscal 2018, the year DHS used to justify the funding request.

While the Border Patrol reported 134,000 pounds seized, DHS told the Pentagon 1,600 pounds were seized. In another error, DHS said Tucson Sector agents seized 52 pounds of cocaine in fiscal 2018. The Border Patrol reported 62 pounds.

The DHS request also said cross-border criminal organizations "frequently employ rip crews," in reference to bandits that steal loads of marijuana from rivals.

Cases of rip crew activity are extremely rare in Tucson's federal court.

Although rip crews "absolutely" are still out in the desert, Brown said, they are "significantly on the decline" due in part to "a lot less marijuana coming across."

A decade ago, reports of rip crews used to come in a few times a week, Brown said, but now "we can go months without hearing about significant rip crew activity."

Cochise corridor

As the wall goes up near Lukeville, orange pickup trucks and heavy machines go back and forth between Douglas, a border town 120 miles southeast of Tucson, and a construction site about 10 miles east of town. There, crews are preparing to build 19 miles of wall to replace post-and-rail fence.

The fence stands about head-high and runs for miles over gently rolling terrain in eastern Cochise County. The purpose of the fence is to stop vehicles from crossing the border, but a person could easily go over or under it.

In the smuggling corridors north of the projects, Border Patrol agents seized more than 15,000 pounds of marijuana from backpackers in the desert and drivers at checkpoints after the marijuana is smuggled through the desert or ports of entry.

In a typical case in Cochise County, a Border Patrol agent operating a camera on Jan. 23, 2018, spotted three people circumventing the checkpoint near Whetstone while carrying backpacks likely filled with marijuana.

The camera operator gave GPS coordinates for the backpackers to other agents. An agent with a canine walked to the coordinates and traced an odor to the side of a wash, where the agent saw three people standing next to the burlap-wrapped backpacks. The backpacks weighed 133 pounds. One man was arrested and told agents he was going to be paid $1,000 to smuggle the marijuana to Tucson.

At the Douglas and Naco ports of entry, customs officers seized about 5,600 pounds of marijuana, 154 pounds of heroin, 136 pounds of meth, 40 pounds of fentanyl and 24 pounds of cocaine in 2018.

The Cochise ports see more hard drugs than in the desert, but in contrast with ports elsewhere in Arizona the ports in Cochise are dominated by marijuana smuggling.

"It's been that way for as long as I can remember," Brown said, adding that smaller ports have less legitimate traffic to mask narcotics smuggling.

The driver of a Ford Explorer pulled into the Douglas port of entry on Nov. 23, 2018. With shaking hands, he gave his ID to a customs officer. A search of the SUV turned up 87 vacuum-sealed packages in the front and rear passenger doors, hollowed out front and rear seats, and the spare tire. The packages contained 100 pounds of marijuana.

The driver said he was recruited two weeks earlier on Facebook to go to Agua Prieta, the Mexican border town south of Douglas. He was told by the man who recruited him that he would drive the SUV into Douglas to buy household items from Walmart and bring them to Agua Prieta, in exchange for a few hundred dollars and a bus ticket back to his hometown.

A Mexican man drove a pickup truck into the Douglas port on Sept. 22, 2018, and customs officers found 39 pounds of fentanyl in the bed of the truck. The man told officers he expected to be paid $5,000 and he smuggled drugs twice a month for the previous year under the direction of a drug-trafficking organization. He would drive to a motel in the Phoenix area and someone would take it for several hours and he would drive back to Mexico the same day.

In the past, this area was known for smuggling attempts known as "drive-throughs," in which drivers hauled massive loads across the border in desert areas.

In a 2018 prosecution stemming from a 2015 incident near Naco, five trucks were loaded with marijuana and driven through a breach in the border barrier that was opened with a plasma cutter.

A decade ago, drive-throughs were "almost a daily occurrence in Arizona," Brown said, but they have "significantly abated" due to more physical surveillance, radar, more agents and physical infrastructure. Now, he hears about drive-throughs less than once a month.

A U.S. Border Patrol vehicle drives by a section of new 30-foot-high wall along the U.S.-Mexico border near the commercial port of entry in San Luis, Ariz.

From everything to everything

"Every bit of infrastructure we can have that impedes the flow of illegal traffic into the United States is helpful," Brown said of the new border wall. "In and of itself, it's not a standalone solution."

As crews tore down the panel fencing that the new wall will replace near Lukeville, two Mexican men waited to pick up pieces of metal that broke off and bounced into Mexico. They said they were planning to sell the metal for scrap.

They did not believe the new wall would stop drug smuggling or illegal border crossings.

"They'll dig holes, tunnels," one of the men said.

Getting past the wall would add just minutes to the three-day walk through the desert to the Arizona town of Why, the other man said.

When asked what was smuggled across the border there, one man said "todo" (everything).

When asked what he thought would still be able to get past the new wall, his response was the same.

"Todo."

About the map:

Data on overall drug seizures was provided by Customs and Border Protection. The Star used records filed in federal court in Tucson and Phoenix to show the smuggling corridors and to break down drug seizures at ports, highways, in the desert, and elsewhere. For clarity, total weights above 100 pounds were rounded.

Court records included most of the hard drugs seized by CBP. Smugglers often abandon loads of marijuana when they are chased in the desert, which leads to far more marijuana appearing in seizure statistics than in court cases. Drug totals in the desert include seizures on highways and in rural areas. Map data is from Natural Earth and NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Sections of planned new walls were plotted from a smattering of court records. And existing border fencing was provided by the Center for Biological Diversity.

The project reporters:

Curt Prendergast has been a reporter for the Arizona Daily Star since 2015 and covers the border, immigration and federal courts. He worked at the Nogales International from 2012 to 2015. Prendergast received a dual master's degree in journalism and Latin American studies from the University of Arizona, and he is bilingual in English and Spanish, with a smattering of Brazilian Portuguese.

Alex Devoid has been a data/investigative reporter at the Arizona Daily Star since June. He previously wrote about the environment for The Arizona Republic. In 2017, he received master’s degrees in journalism and Latin American studies from the University of Arizona. Devoid has also lived in Nicaragua and is bilingual in English and Spanish.

Photos of the U.S–Mexico border in Arizona

Photos of the U.S. – Mexico border fence

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A dog stands on a road commonly used by Border Patrol near Slaughter Ranch Museum Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A border monument on the Mexico side of the border seen east of Douglas Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge sits on the U.S. side of the border with Mexico east of Douglas Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A bull and cow graze near the site of new wall construction east of Douglas Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The border seen stretching from hills east of Douglas into the Guadalupe Mountains Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

Flowers grow around border fencing near the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

Construction equipment set up at the site of new border wall construction on the US/Mexico border east of Douglas Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A Border Patrol tower on the hills east of Douglas Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

Memorials place on graves at Julia Page Memorial Park in Douglas which sits along the U.S./Mexico border Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A car drives through Douglas on a road parallel to the U.S./Mexico border wall Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The Slaughter Ranch homestead Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A lake on the Slaughter Ranch Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

A toy rocking horse placed on the side of East Geronimo Trail with a sign advertising five minute pony rides for 25 cents Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

Highway 2 in Mexico winds its way to Agua Prieta Thursday, Sept. 27, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The vehicle in a ditch was driven through the international border fence in Agua Prieta, Mex., into Douglas, Arizona in July 1987.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

Mexican citizens run back into Agua Prieta, Mexico through a hole in the border fence at Douglas, Ariz., after the U.S. Border Patrol scared them back across the border in 1997.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The Raul Hector Castro Port of Entry on May 1, 2018, in Douglas, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near Douglas, Ariz.

Updated

The Douglas, Ariz., border crossing in 1968.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

U.S./Mexico border fencing next to a old church building in Lochiel Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

Old border posts line the U.S./Mexico line near Lochiel Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

A Soal Off Roading sticker placed on a U.S./Mexico border post near Lochiel Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

Mountains in Santa Cruz County seen from Duquesne Road between Nogales and Lochiel seen Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

A monument in Lochiel marking where Fray Marcos De Niza entered Arizona Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

Brothers Ramon and Ed De La Ossa mend fencing on their family's ranch in Lochiel after moving cattle Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019. The ranch which used to span both sides of the U.S./Mexico border has been in the family for three generations.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

Ed De La Ossa mends fencing on his family's ranch in Lochiel Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019. The ranch which used to span both sides of the U.S./Mexico border has been in the family for three generations.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

Ed De La Ossa moves cattle on his family's ranch in Lochiel Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

U.S. Customs inspector Helen Mills, right, greets Mexican counterpart Raymundo Aguirre Castillo at the U.S. - Mexican border station at Lochiel, Ariz., in 1979.

U.S. – Mexico border near Lochiel, Ariz.

Updated

The US Customs building, right, at Lochiel, Ariz., is just a short distance away from the international border in May 1972. For ten years, Mills has been managing the port of entry, which is mostly made up of five houses, a school and an vacant church, inspecting vehicles as they head into the US. During the week, from Monday through Saturday, Mills opens the border gate from 8 am to 10 am and from 4 pm to 6 pm. On Sunday the gate is open from 8 am to 6 pm. In that time barely a dozen vehicles make their way across the border but it is a major convenience to the local residents.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Pedestrians walk to the Nogales port of entry Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

A pedestrian walks across North Grand Avenue in Nogales near the U.S./Mexico port of entries Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer R. Hernandez uses a density-measuring device on the rear quarter-panel of a Mexico-bound passenger vehicle at the DeConcini Port of Entry on Nov. 2, 2016, in Nogales, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

A Customs and Border Protection officer makes a visual check of a man's identification at the DeConcini Port of Entry on Feb. 15, 2017, in Nogales, Ariz. Busts of fraudulent border-crossing documents and the use of someone else's documents plummeted in Arizona and the rest of the border in the past decade.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Northbound commercial truck traffic lined up for inspection at the Mariposa Port of Entry on March 28, 2017, in Nogales, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

In the commercial lanes a semi truck stops between the lanes looking for the first available opening at the Mariposa Port of Entry in 2015.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Javier Castillo inspects a north-bound Mexican tractor-trailer at the Arizona Department of Transportation's inspection facility at the Mariposa Port of Entry on Sept. 19, 2017, in Nogales, Ariz. ADOT's International Border Inspection Qualification program, led by ADOT's Border Liaison Unit, teaches commercial truck drivers what to expect during safety inspections when they enter Arizona ports of entry.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

A Border Patrol truck parked near the commercial port of entry in Nogales.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

An illegal alien scales the U.S.-Mexico fence back toward Sonora after a Nogales Police Department officer, right, spotted him west of the Mariposa Port of Entry, Nov. 15, 2018, in Nogales, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Kory's, a store catering to wedding, quincea–era and formal gowns, located at 15 N Morley Ave, Nogales, Ariz., sits katty corner to the Morley Gate Border Station on January 30, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Sun shines through the U.S.-Mexico bollard fence west of the Mariposa Port of Entry, Nov. 15, 2018, in Nogales, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near Nogales, Ariz.

Updated

Children from Nogales, Sonora, climb through a hole in the international border fence to trick-or-treat in Nogales, Arizona, on Halloween in 1987.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Border monument #166 is seen on the right as construction continues on the new 30-foot tall bollard fence that replaces old U.S./Mexico border fence two miles east of the Lukeville, Arizona port of entry on October 8, 2019. Photo taken from Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Construction continues on the new 30-foot tall bollard fence along the U.S./Mexico border two miles east of the Lukeville, Arizona port of entry on October 8, 2019. Photo taken from Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A Mexican worker rides his horse along a road south of the U.S./Mexican border wall on his way back into Sonoyta Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

New paneling of border wall seen about three miles east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Old mesh paneling is removed in preparation for new wall to be built about three miles east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A construction worker prepares cables to lift a piece of the 30-foot tall bollard fence along the U.S./Mexico border fence two miles east of the Lukeville, Arizona port of entry on October 8, 2019. Photo taken from Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Border Patrol Officers to the side of a worksite about three miles east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry where new border wall is being installed seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Old wall east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Raised wall east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A work site east of the Lukeville/Sonoyta port of entry seen from the Mexico side of the border line Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Normandy fencing placed against a section of border fence west of Lukeville Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A semi passes by Quitobaquito Springs as it drives along Highway 2 in Mexico Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

An area referred to as "flood gate" along the U.S./Mexico border near Sasabe, Ariz. is on the list of the Department of Homeland Security’s priorities for building a border wall, but no funding has been allocated yet. September 16, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

Vehicle barriers mark the U.S./Mexico border within the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge in Sasabe, Ariz. on September 16, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A portion of the U.S./Mexico bollard border fence ends on the right and vehicle barriers begin within the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge in Sasabe, Ariz. on September 16, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection Integrated Fixed Tower, left, near Sasabe, Ariz. on September 16, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near Sasabe and Lukeville, Ariz.

Updated

The new 30-foot tall bollard fence that replaced old U.S./Mexico border fence can be seen on the left. It's located about miles east of the Lukeville, Arizona port of entry on October 8, 2019. Photo taken from Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

A US Border Patrol vehicle seen next to a section of new 30 foot high wall along the US/Mexico border near the commercial port of entry in San Luis Thursday, Aug. 8, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

Old fencing is taken down along the United States/Mexico border seen from the northern end of San Luis, Mexico, Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

A security guard stand in a construction site where a new fence will be placed on the United States/Mexico border seen from the northern end of San Luis, Mexico, Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

Old fencing against new fencing along the United States/Mexico border seen from the northern end of San Luis, Mexico on Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

Crews prepare ground for a new fence to be placed on the United States/Mexico border seen from the northern end of San Luis, Mexico on Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

Vehicles in line to enter the United States from San Luis, Mexico on Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

New fencing along the United States/Mexico border seen from the northern end of San Luis, Mexico on Aug. 7, 2019.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

A new section of fencing on the U.S. - Mexico border in California, just west of Yuma, Ariz., in 1993.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

Sand drifts through the "floating fence" that marks the border running through the dunes, Wednesday, July 25, 2018, west of San Luis, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

A sign warns of the dangers of trying to swim the All-American Canal just north of the Mexican border, Wednesday, July 25, 2018, west of San Luis, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

A long string of lights illuminate the no-man's land between the triple fencing of the Mexican border, Wednesday, July 25, 2018, San Luis, Ariz.

U.S. – Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz.

Updated

The border fence comes to an abrupt end at the currently dry Colorado River, Thursday, July 26, 2018, west of San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora.