A couple mornings each week, Marketa Jansky wanders outside the Casa Maria Soup Kitchen asking the same question of anyone milling around: Would you like to get the vaccine today?

As a nurse practitioner with one of El Rio Health‘s homeless outreach teams, Jansky and her colleagues are focused on bringing the COVID-19 vaccine to people living in shelters or on the streets.

So far, El Rio providers have fully immunized nearly 700 Pima County residents experiencing homelessness but more often than not, people are turning down the shot.

“Some of the patients don’t believe in the vaccine or they believe it’s unsafe to use. They are afraid,” said Luis Murillo, a registered nurse who was working with Jansky last Tuesday. “We’re trying to work really hard to inform them about the misinformation going around. Our goal is to develop vaccine confidence.”

Not unlike other vaccine skeptics, some of Murillo and Jansky’s patients have been influenced by friends or what they’ve read on social media.

That’s what initially held back James Ramirez, who didn’t get the vaccine when it first became available because friends said the shots contain aborted fetal cells.

But after learning more from El Rio staff about the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, he changed his mind.

He was one of five patients who got immunized last Tuesday in a makeshift clinic El Rio workers set up for their weekly visits to the south-side soup kitchen.

‘Non-judgmental outreach’

Concerns people experiencing homelessness have about vaccines “aren’t that different from concerns other people have,” said Jason Thorpe with Tucson’s Housing & Community Development Department.

Thorpe and others, including the Tucson-Pima Collaboration to End Homelessness, recently put together a webinar about how to improve vaccine confidence. It can be downloaded for free at tpch.net/resources/vaccine-toolkit.

Mistrust of health-care workers among people living in shelters or on the streets is “deeply rooted,” said Katie League, COVID-19 project manager with the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

“We find that the relationships that a person has with their providers is a very large motivator in determining if they are ready to be vaccinated,” she said. “We know that it may take one, two, five, or 20 times for a person to be open to an idea, and that consistent, non-judgmental outreach where we leave the door open but allow for autonomous decision-making is essential to earning someone’s trust.”

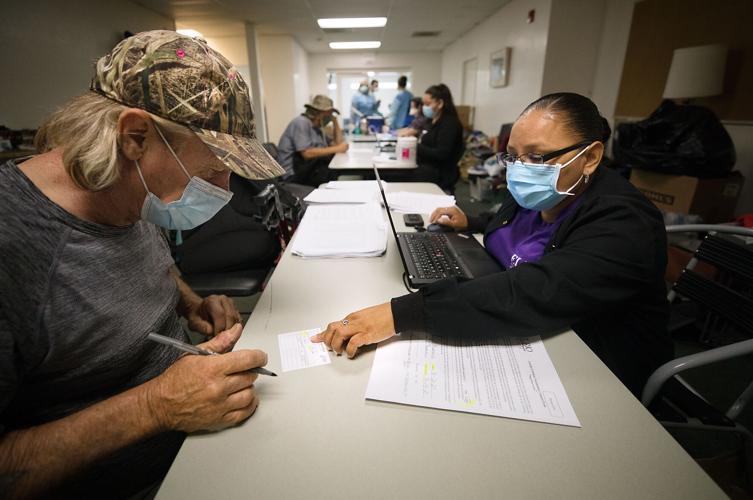

Sonia Camacho, a care coordinator with El Rio Community Health, helps Mark Kemmis register for the COVID-19 vaccination at a pop-up clinic at the Primavera Foundation Homeless Intervention & Prevention Drop-In Center in Tucson.

Overall, she said, “trust has a very big impact on a person’s decision-making process.”

These are familiar themes to Kim Hunter, a licensed professional counselor with El Rio who often accompanies the street medicine teams as they move around the county. Hunter and her colleagues work to build relationships with the people they’ve been entrusted to help.

“It’s all about establishing rapport and establishing trust and correcting all the misinformation that was provided early on,” Hunter said of the pandemic.

As the county’s largest local provider of medical and dental services for uninsured people and Medicaid recipients, El Rio Health and its street medicine teams have already been working regularly with people in shelters as well as those living in parks or encampments along Tucson’s many washes.

The goal, ultimately, is to establish an ongoing relationship, and help people find housing as well as a regular primary care provider.

Now, in the pandemic, dispensing the vaccine to as many people as possible is vital, especially for such a high-risk population. League said people experiencing homelessness are more likely to have serious symptoms and often have poorer health outcomes if they do get COVID-19.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique risk for people experiencing homelessness for a variety of reasons — some disease-specific, and others pertaining to the impact the disease has had on the community around the person,” she said, explaining that many of the support services people rely on have been stressed over the last year.

“This disease has disproportionately impacted people of color and has been more severe for people with multiple health conditions, both of which are disproportionately represented among people experiencing homelessness.”

‘Let’s get it done’

On the last Friday in April, El Rio nurse practitioner C.J. Collins headed out early with doses of Johnson & Johnson packed in his truck, a first in nearly two weeks.

The one-dose COVID-19 shot, ideal for patients El Rio workers see in homeless encampments and shelters, was paused nationwide after an extremely rare yet severe blood clotting problem was reported in six people, out of nearly 7 million doses administered.

Coy "CJ" Collins, a licensed nurse practitioner with El Rio Community Health.

During the Johnson & Johnson hiatus, El Rio health workers used the Moderna vaccine because one dose does offer some immunity, said Dr. Joy Mockbee, medical director for Cherrybell Health Center and El Rio’s street outreach teams.

If the person doesn’t get the second shot from a street team, Mockbee said there’s a good likelihood the patient will show up later in El Rio’s system and can get their second dose that way.

“We try to meet people where they are at,” she said. “This is about building long-term relationships.”

Collins’ first stop that April morning was to visit a couple he’s been helping for a while now.

Joy Severns and her partner, Andres “Rocky” Contreras, live in a tent near the Aviation Bikeway, which runs along East Golf Links Road.

When Collins first brings up the vaccine, Severns is skeptical. She asks about the blood clots, and then whether it’s safe for Rocky.

“We’ve been talking about it,” Severns said. “I’m just kind of hesitant is all. I don’t like needles.”

Coy "CJ" Collins, a licensed nurse practitioner with El Rio Community Health, left, talks to Joy Severns, right, about the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine at an encampment near S. Alvernon Way and Golf Links Road in Tucson.

Collins explains the risks and benefits. Contreras agrees after asking a couple more questions.

After a few more minutes, Severns agrees, too: “Let’s get it done.”

She scrunches her face as Collins dispenses the vaccine into her arm. He asks her if she’s OK.

“Yep, I’ll be all right,” she says. “I’ll still be on the go.”

‘I don’t get sick’

Luis Murillo, a registered nurse with El Rio Community Health, talks to people about the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at a pop-up clinic at the Primavera Foundation Homeless Intervention & Prevention Drop-In Center.

For the next four hours, Collins drives and walks to reach more people living in encampments along the wash.

Out of the 12 people he encounters, only four agree to the shot.

At one site, a woman comes out of a tent and listens as Collins introduces himself but then shakes her head when he offers the vaccine.

“Not right now,” she says.

At another stop, where several people are living, one person says yes: a woman named Amanda Clough.

Her friend shakes his head when Collins asks if he wants to be immunized against COVID-19.

“I have a strong immune system,” Travis Goodwin says. “I don’t get sick.”

At a site further east along the wash, a military veteran named Ken Tarro immediately agrees to the shot but two others living in the encampment are not interested.

Collins talks to them about it briefly and says he’ll swing by another time to see if they’ve changed their minds.

Tarro, meanwhile, says he’s wanted to get vaccinated for a while. He’s obviously relieved Collins is there.

As Collins prepares the shot, Tarro asks if he’s the first one who said yes to Collins that day and then smiles when Collins says no.

“So there are other wise people out there,” Tarro says, laughing. “I know I’d rather be safe than sorry.“