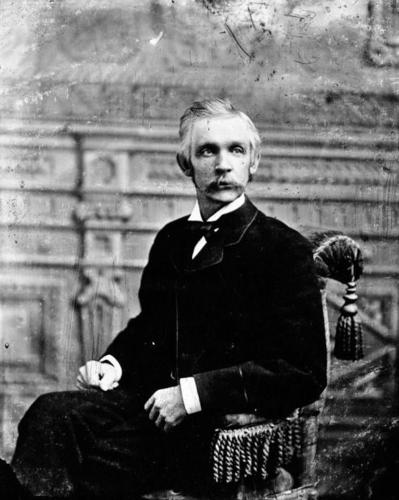

James H. Toole, born in 1824 in New York, began his career in the mercantile business in New Orleans, but traveled to California during the gold rush in 1849.

He was a miner in Placer County until 1861, when he joined the Union Army. He became a 2nd lieutenant in Company G of the California Column, and with his company he came to Tucson in 1862. While here, he served as acting assistant quartermaster and commissary from May 30, 1962, to Jan. 9, 1863, then was promoted to 1st lieutenant and transferred to field and staff as regimental quartermaster on Jan. 10, 1863.

James H. Toole came to Tucson with the Army in 1862 and was first elected mayor in 1873.

He was transferred to Company D on May 19, 1863, in Tucson, and remained here until he was transferred to Las Cruces, Territory of New Mexico, on Nov. 28, 1864. His final stop during the Civil War was El Paso, Texas, where he was discharged on April 5, 1865.

Toole returned to the Arizona Territory and, in 1867, purchased the sutler’s store at Tubac, where he also provided a club room for military officers.

For a few months, in late 1868, he was the adjutant general of the Arizona Territory, in charge of the state militia. The following year he sold his interest in the La Paz silver mine 12 miles west of Tucson.

Two years later, he was listed in the 1870 U.S. Census as a retail merchant, with $2,500 in real estate and $20,000 in his personal estate. That same year, on Oct. 3, 1870, Gov. Anson Peacely-Killen Safford appointed him to the Pima County Board of Supervisors to replace E.N. Fish.

In April, 1872, Toole’s poor health induced him to leave Tucson and return to New York. While on leave, John B. “Pie” Allen (namesake of the Pie Allen Neighborhood) rented his place. He returned in late October with his health restored and, by December, he — along with Gov. Safford, Judge Titus and Dr. J.C. Handy — were looking into mines in Sonora, Mexico.

In January 1873, Toole was elected mayor of the Village of Tucson for a year. That April, he wed Louise M. Dexter, and the couple spent their honeymoon touring Guaymas and other towns in Mexico. They would go on to have five children: James Jr., Robert, Richard, Anna Belle and Catherine.

He was a popular mayor and won 100 of the 101 votes cast in the 1874 re-election. On May 1, 1875, the Arizona Citizen newspaper reported that the by-then former mayor was spending his time conducting research in the “exact sciences.” He was experimenting with ways to get his hens to produce bigger eggs. Toole challenged anyone in Tucson to a competition in producing a larger egg.

On Sept. 23, 1876, the Arizona Citizen declared to a hopeful, but trainless, Tucson: “In three years, the people of this section, and very likely those of Tucson, will daily hear the cheery and energizing sound of the locomotive whistle.”

Toole was once again elected mayor in January 1878. By November, surveyors for the Southern Pacific Railroad were in Tucson, surveying out a route for the train.

L.C. Hughes, editor of the Arizona Daily Star, wrote on May 1, 1879: “The first sound of the locomotive’s whistle will be the notice of a new life for our city and its vicinity, and we look forward to the time when the last spike is driven that connects Tucson with the outside world by a band of iron with a degree of pleasure that we cannot describe.”

|

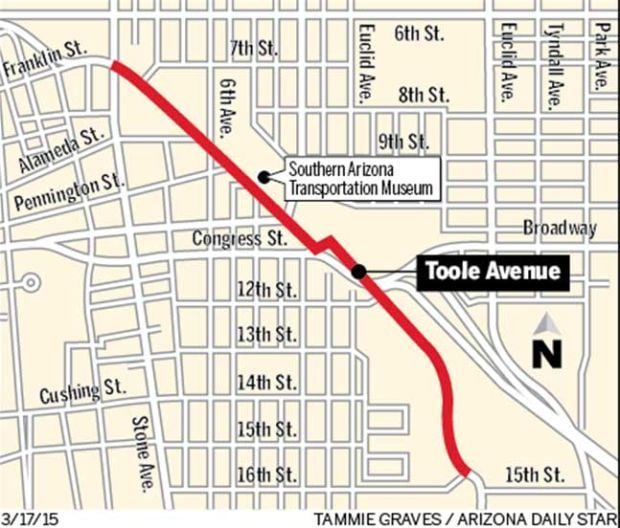

Toole, who had been re-elected mayor for a fourth term, and the City Council met with Col. George Gray, chief engineer for the Southern Pacific Railroad, on May 14, 1879. Gray asked for a 100-foot- wide strip of land for tracks to be laid at a northwest to southeast angle across the undeveloped northern part of the village. He also requested a 350-foot wide parcel of land for a freight and passenger depot, as well as a dozen city blocks close by for maintenance facilities, repair shops and roundhouses. All of the railroad’s wishes were granted, free of charge.

Toole and the council called a special election to decide if $10,000 worth of bonds should be issued to defray the cost of obtaining sufficient right-of-way for the railroad. Voters approved the issue and the city government began acquiring the land requested by the railroad.

Toole wrote to Gray: “It affords me pleasure to say that our whole people have heartily cooperated with the corporate authorities in accomplishing the very liberal requirements of your company, and we confidently look for the early completion of your road to Tucson to give a new impetus and prosperity to our city.”

On Aug. 8, 1879, the Arizona Citizen announced that, two days earlier, the City Council had passed Ordinance No. 20, providing for the opening of Toole Avenue.

On March 20, 1880, R.N. Leatherwood, then the mayor of Tucson, greeted the Iron Horse and officials of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Estevan Ochoa — who, along with Pinckney R. Tully, owned one of the most successful freighting businesses in town — was one of many prominent citizens to make speeches. Ochoa presented Charles Crocker, a top official with the railroad, with an engraved silver spike crafted from the first bullion produced by the Tough Nut Mine in Tombstone. Anyone who was anyone in Tucson attended the celebration of the arrival of the train that day.

Toole later became a principal member of the banking firm of Safford, Hudson & Co. (later called Hudson & Co.). When the firm went out of business, the loss took a toll on Toole, both financially and mentally. He lost everything except for his home on the corner of Stone Avenue and Ochoa Street. After sending his wife and children to Beaver Falls, Wisconsin, to stay with her relatives, he boarded a train to join his family. Stepping off the train, onto the platform in Trinidad, Colorado on Oct. 15, 1884, he shot himself and died instantly.

He was buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin.

Note: It’s believed that Toole’s children went to live with relatives in Iowa, since they appear in the 1885 Iowa State Census.