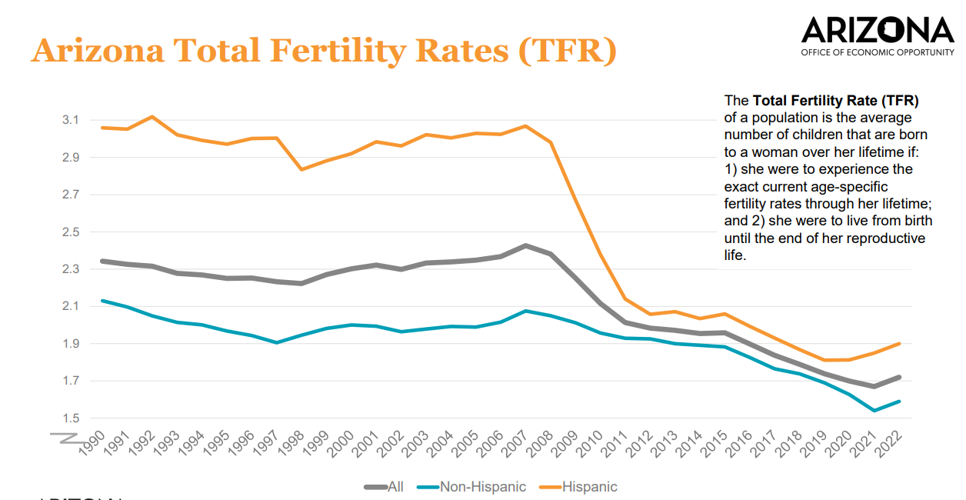

Few people noticed when a dramatic shift happened in Arizona after the 2008 economic crash.

Arizona’s Hispanic women, especially, started having a lot fewer kids.

Between 2008 and 2012, Latinas in the state went from having three children per woman on average, to two, a 33 percent drop in just four years. Overall, Arizona had the biggest decline in fertility rates of any state between the first and second decades of the century.

“This is unprecedented,” Arizona’s state demographer, Jim Chang, told the Arizona Board of Regents last month.

It’s part of a broader trend playing out worldwide. Fertility rates (the number of children per woman) have dropped well below the level needed to replace the existing population.

That may seem like a good thing — it can lessen our human impact on the overburdened Earth. But it can have big negative implications for a country’s economy and overall well-being, as fewer young people are available to work and must support more older ones.

In Arizona, “We are now at 1.7, which is quite a bit below the replacement level, which is 2.1,” Chang said. “I think we are the highest among developed countries. In South Korea, this number is 0.7.”

In China last year, the population actually decreased for the second year in a row. And trends suggest a steep and dangerous drop that could halve the country’s population by the year 2100. Even with family-size restrictions lifted in China, adults are choosing not to have more.

Whether to have kids is such a deeply personal decision that it’s often relegated to private conversations, but it’s emerging again as a real-world public policy issue. Abortion bans, climate collapse, economic uncertainty and demographic cliffs all make these private choices a public concern.

In Arizona, the 1864 abortion ban — which has not taken effect after the recent Supreme Court decision confirming it as the law — is likely having an impact on women’s comfort with getting pregnant. Medical decisions could be taken out of their doctors’ hands.

“I have two children, but I might want more,” Eloisa Lopez, who is executive director of Pro Choice Arizona, told me. “I would be terrified to be pregnant in a state with a ban.”

A question of morality

American families have been shrinking since long before Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. Economic growth and the availability of birth control convinced adults to have fewer kids.

The shrinking of the American family was a movement Texas A & M University historian Trent MacNamara describes as “totally informal, largely invisible, very democratized.”

“You’d struggle to find a more ‘social’ social movement,” MacNamara, the author of the book Birth Control and American Modernity, said in an email. “It was just a bunch of anonymous people who gradually rethought the place of kids in a good life, across millions of little kitchen-table conversations.”

An “unprecedented” decline in Arizona’s fertility rate happened in the years after the 2008 economic crash. Hispanic women went from having three children per woman, on average, to two over just a four-year period. Arizona had a bigger decrease in its fertility rate from 2001-10 to 2011-20 than any other state.

Since then, a segment of American culture has extended the logic of having fewer kids further and decided to have none at all. Greg Scott, vice president of the conservative Center for Arizona Policy, attributed the change to a “cultural mindset that children are a net detriment to a flourishing life.”

It also became a question of ethics, especially after Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb was published in 1968. The book predicted an era of mass human starvation due to humans’ overuse of resources. It turned out to be wrong. The Green Revolution and other changes drove down global hunger in the period when Ehrlich predicted mass starvation.

But the impact of concerns about overpopulation on our planet lingered and have been strengthened as the climate turns hotter. When I questioned my thousands of friends on Facebook to see if anyone I know has decided not to have children due to environmental concerns, a growing stand among young adults, several said yes.

One was Tucsonan Stacey Auch, who told me in a later conversation that she decided about 15 years ago that she does not want to have children. She doesn’t want to add another person to the planet’s load, Auch said, and she also worries about what life will be like for herself, let alone a new child, as the climate changes.

“In addition to my concern for a child or myself, I really like my planet,” Auch said. “We continue to tear down forests and harm wildlife. Those are things that I hold dear.”

The love of family

I do too, and yet I find myself wishing increasingly that more people were having children. Not people who don’t want children — they shouldn’t have them, of course. But people who love children and are on the fence for other reasons.

My wife’s six siblings have been circulating through our house recently as we care for their aging mother (my mother-in-law) who lives with us. Being part of a big family can be hard, especially when the kids are young and competing for the parents’ attention. But when they’re grown, this ability to band together is unbeatable.

I am one of two children myself, and the father of two, but my growing appreciation for bigger families puts me more in line with conservative trends than with my fellow political liberals. A subculture of young conservatives, especially strong in Silicon Valley, is trying to encourage bigger families, at least for people like them.

Tucson Republican Blake Masters, a Silicon Valley veteran, pushed this idea during his 2022 run for U.S. Senate, and he’s doing it more aggressively in this year’s primary run for U.S. House as he attempts to defeat unmarried rival Abraham Hamadeh.

“I’ve got a wonderful wife, I’ve got four beautiful boys. That’s called skin in the game,” Master said in a video his campaign recently posted. “What we don’t need is someone with no wife and kids, no skin in the game.”

Tyler Bowyer, Arizona’s indicted, departing member of the Republican National Committee, summarized the neotraditional spirit bluntly on his Twitter account in April 2023: “HOMESTEAD AND HAVE MORE CHILDREN.”

It’s not right to judge people who don’t have children, as Masters has. People’s choices and circumstances are their own.

But I’m worried about those choosing not to have children out of fear of climate change. A January letter to the editor of the Wall Street Journal, from an older man in Minnesota, summarized why I fear they could regret their choices.

“I was a college student when I read Mr. Ehrlich’s ‘The Population Bomb,’” the letter reads. “I took it to heart and now have no grandchildren, but 50 years later the population has increased to eight billion without dire consequences. I was gullible and stupid.”

Making life easier for parents

Countries facing low birthrates have struggled to change them. Viktor Orban’s Hungary, beloved by conservatives, has put in place tax breaks and other financial incentives that amount to about 5% of the country’s GDP. Still, it has barely bent the fertility rate upward and has not reached replacement levels.

For now, Arizona doesn’t have to worry much about achieving a replacement birth rate. We have plenty of migration that can make up for a lack of young people, and we need to worry about whether we have enough water anyway.

Still, we should worry about the things that cause people who might want children not to have them. The accessibility of prenatal medical care, quality jobs and affordable housing are key factors that people take into account when considering having children, Lopez said.

Any rebound in births would have to be organic, as was the reduction in family sizes, MacNamara said.

“I tend to think that the best pronatal policies are not framed in pronatal terms,” he said via email. “They’re just policies that make life easier for families and parents.”

Across the political spectrum, we might be able to agree on that.