Upset with what he said are lies being told about his efforts to protect groundwater, the No. 2 Republican in the Arizona Senate is lashing out at a veteran House Republican who has for years bottled up various efforts to regulate rural pumping.

In a memo to colleagues, Senate Majority Leader Sonny Borrelli said Rep. Gail Griffin misrepresented legislation he and Rep. Leo Biasiucci are trying to craft to let rural counties set up governing districts that could regulate how much water is pumped from the aquifers beneath them.

Sen. Sonny

Borrelli said the issues range from how these “local groundwater stewardship areas’’ could be formed, to who would sit on the panels.

But he said Griffin’s latest action is just a piece of a larger problem. Various proposals to give local communities some control over groundwater pumping have died over the years as Griffin, a Sierra Vista Republican who chairs the House Committee on Land, Agriculture and Rural Affairs, has refused to give them a hearing.

That has left rural communities, including those he represents, at risk, said Borrelli, a Lake Havasu City lawmaker.

Rep. Gail

“Western Arizona is completely unregulated,’’ he told Capitol Media Services. “And everybody wants to stick their straw in our district.”

This isn’t a new complaint. Regina Cobb, a former House Republican who represented the same area of northwest Arizona for eight years, said she, too, found her proposals to help deal with a declining water table dying at Griffin’s hand.

The issue is aggravated by massive pumping by new farms that have popped up in rural areas of the state in recent years — the areas lacking rules about groundwater use.

Once an area is depleted of groundwater, not just the farms will go away. Cities and towns and the rural residents who rely on that water will have nowhere else to turn.

“Liberal agenda”

What particularly galls Borrelli is that Griffin, in a memo distributed to county supervisors and others, said his proposal was crafted by the Environmental Defense Fund and is being advanced by “radical out-of-state environmental organizations headquartered in New York and other elitist cities along the coasts.’’

“Rep. Griffin is attempting to portray me and this bill as part of a liberal agenda,’’ he said.

Borrelli, who describes himself as fighting “those on the Left ... who want to chip away our freedom,’’ said his draft proposal was based on input from Republicans and Democrats in rural areas. He said it includes language from everyone from mining interests such as Freeport McMoRan, to real-estate industry promoter Valley Partnership, to county supervisors, the Arizona Farm Bureau and rural water associations.

He also said the claims Griffin made about his legislation this year were deliberately misleading.

Griffin defends her analysis. She said it is based on a point-by-point review of the content in the legislation proposed by Borrelli and Biasiucci.

Borrelli countered this was an initial version of his bill that was meant only to be a starting point.

“It’s always a work in progress,’’ he said. If a consensus could not have been reached, the measure would have died, he said.

Instead, he said, Griffin chose to bury it in committee, before any work could be done, and then shoot at the preliminary version in claiming to county supervisors that the measure — which she called the work of the Environmental Defense Fund — “could be abused to change the social, economic and political makeup of your district.’’

Griffin’s power

The death of this year’s legislation aside, Borrelli said there’s the question of Griffin being the traffic cop at the Legislature who can stop any water bill from ever getting to the full House, an ability she has because House speakers who assign the bills choose to send it to her committee.

“That decision always falls to the speaker,’’ said Biasiucci.

But Cobb, who had her own bills shelved by Griffin for years, said speakers have the unilateral power to assign “good water legislation’’ to other committees, such as the House Government Committee chaired by Rep. Tim Dunn, R-Yuma.

“The leadership has to make a decision,’’ Cobb said. “But they’ve chosen to put it in her committee and allow her to sit on it.’’

Current House Speaker Ben Toma of Peoria, who assigned the Borrelli and Biasiucci bill to Griffin’s committee this year, declined to comment, even by text, saying he is on an anniversary trip to Romania.

Borrelli said there’s no reason to give that much power to Griffin, who represents much of southeastern Arizona, including Cochise County.

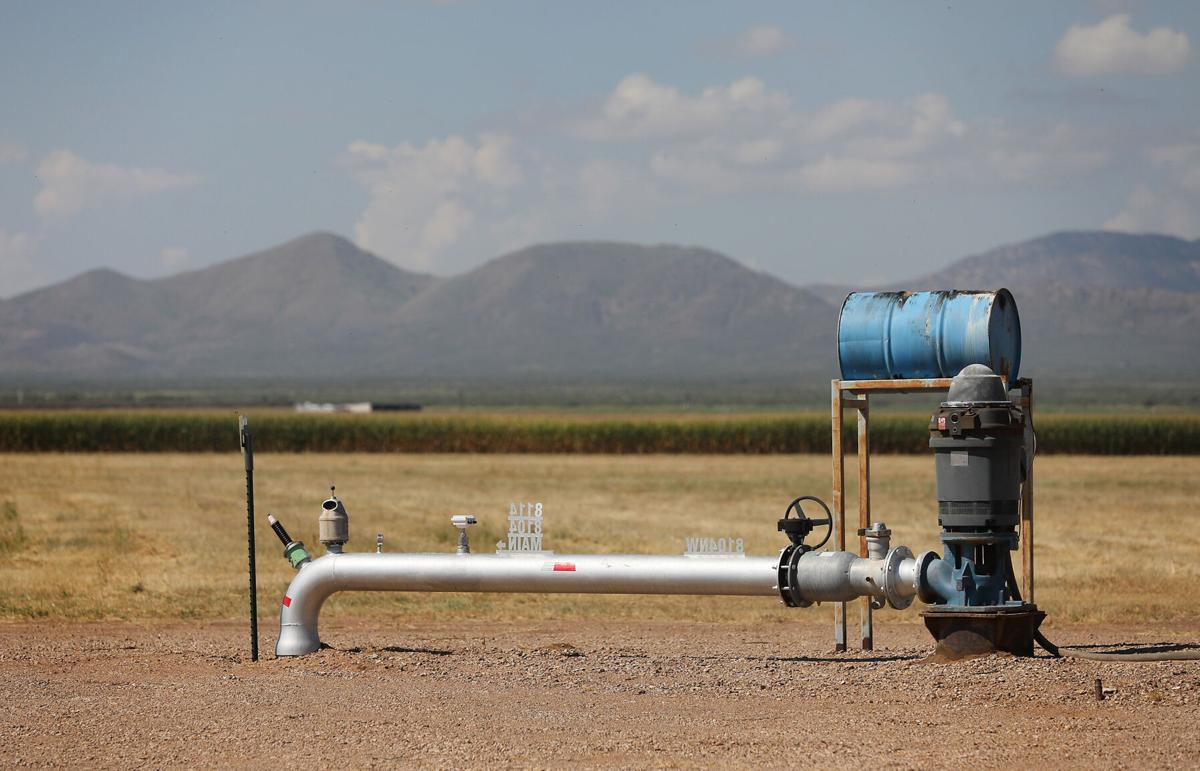

Various proposals to give local communities some control over groundwater pumping have died over the years as Rep. Gail Griffin, a Sierra Vista Republican who chairs the House Committee on Land, Agriculture and Rural Affairs, has refused to give them a hearing. In this photo, an agricultural field in Elfrida is shown.

“I think she thinks that she’s a water guru, and all things rural,’’ he said. But Borrelli said that doesn’t wash.

“Look, your county is different than my county,’’ he said. “I don’t mess around in your county. And I ask the same respect.’’

Borrelli said that means Griffin should not block local efforts to deal with their individual situations.

“We’re trying to get something done in our county,’’ he said.

“We have a lot already”

Griffin told Capitol Media Services there already are water conservation options for areas outside the state’s six Active Management Areas. Those six areas, including Phoenix and Tucson, have comprehensive regulations about the withdrawal and use of groundwater.

She specifically cited 2007 legislation that allows counties, cities and towns outside those regulated areas to require new subdivisions to have an adequate water supply, defined as sufficient groundwater, surface water or effluent to satisfy the needs of the proposed use for at least 100 years. But she said supervisors in just two counties — Cochise and Yuma — adopted that authority.

“We have a lot already in statutes,’’ Griffin said.

She said the state’s Water Infrastructure Finance Authority continues to approve projects to increase water supply.

“We have lots of tools in the toolbox,’’ she said.

But that 2007 legislation, even if counties choose to adopt it, is nowhere near as rigorous as what is required in areas with Active Management Areas.

The requirement for an “adequate’’ water supply is less rigorous than the “assured’’ water supply that must be proven before building in an AMA, including requirements to show the water is continuously and legally available.

Mohave County Supervisor Travis Lingenfelter acknowledged counties have the authority to adopt such a plan, but said that won’t help many areas of the state.

“It’s only applicable to residential, commercial, industrial,’’ Lingenfelter said. “It doesn’t apply to agriculture.’’

“Agriculture from Middle East”

It’s not like the farms causing much of the problem in his area have been around for years, Lingenfelter said.

“Agriculture from the Middle East and from California, they were here last,’’ moving in to take advantage of lax water laws in rural Arizona and the inability of a county like his to do anything about it, he said.

“It’s still the wild, wild West in Arizona,’’ he said. “You can construct and install as many wells as you want, as large as you want, you can pump as much water as you want.’’

That last point is particularly critical, he said, making it impossible for local officials to know how much water they have.

“The one thing we have to have is certainty in our water planning,” Lingenfelter said. “We don’t have that.”

Consider, he said, the Hualapai Valley basin, about 1,820 square miles stretching from Lake Mead to just south of Kingman, a city dependent on groundwater.

The state Department of Water Resources designated it as an “irrigation non-expansion area.’’ But all that does is require monitoring of wells and assure there is no new agricultural use. It provides no ability to enact or enforce conservation requirements.

Lingenfelter said DWR has computed that about 44,000 acre-feet of water comes out of the basin every year. An acre-foot is nearly 326,000 gallons, with various estimates saying that is enough to serve between two and three average households a year.

Recharge, by contrast, is about 10,000 acre-feet a year.

“So we have a groundwater deficit every year of 34,000 acre-feet,’’ he said. “Sixty percent of that, DWR will tell you, is the corporate agriculture that’s moved in over the last nine years.’’

Imposing a requirement for a 100-year water supply that applies only to residential, commercial and industrial would “further hand over the basin to agriculture,” Lingenfelter said.

“We don’t have a 100-year supply”

Cobb said it’s even more basic than that. She said adopting such a requirement makes no sense for her area of the state.

“We don’t have a 100-year supply, or anywhere close to that,’’ she said.

Former Rep. Regina Cobb

There’s something else Griffin did not mention in touting the 2007 legislation as a form of relief for rural areas.

She sponsored a bill in 2016 to allow cities in counties that have adopted such a rule to opt out if they meet other qualifications, like having a water-recharge program, adopting a water-conservation program, putting only low water-use plants on rights of way, and funding programs to replace high water-use plumbing fixtures.

The bill was widely understood to help a developer who hoped to make an end-run around legal problems that thwarted its efforts to construct a 7,000-home development in Sierra Vista.

Griffin’s measure got all the way to the desk of Republican Gov. Doug Ducey who called it a “bad bill’’ and said it “would encourage a patchwork of water ordinances through our cities and leave our water supplies in peril.’’

“Ensuring the certainty and sustainability of Arizona water is a top priority,’’ Ducey ssaid in his veto message. “I will not sign legislation that threatens Arizona’s water future.’’

Biasiucci, like Borrelli, said he is frustrated with an inability to get proposals advanced to the full Legislature.

“All I care about is that, as a state, we position ourselves in a way that will allow us to have an adequate water supply for generations to come,’’ said the Lake Havasu City Republican.

That also means recognizing that one size does not fit all — and that individual communities need the authority to come up with their own solutions, Biasiucci said.

“My district has different needs than Gail’s district,’’ he said. “And nothing will ever get solved until we sit down, understand the wants and needs of each district, and develop a plan that will work for everyone. It’s not an easy thing to do. But it’s time we put our differences aside and get something done.’’

“Your well is going to go dry”

Cobb acknowledged the problem of enacting water regulation for rural areas is not limited to Griffin killing proposals in her committee. She said there is a belief among some lawmakers that there is a “personal property right’’ to groundwater.

“This is a myth we keep trying to dispel,’’ said Kathleen Ferris, senior research fellow at the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

She said the Supreme Court has said there is a property right to water “once you pump it.’’

“But when it’s under the ground, it belongs to no one,’’ Ferris explained. “And it’s a public resource that the state may regulate under its police power.’’

Saying people can pump what they want from underneath their land is akin to a neighbor setting up a trailer on their property but then running a line to someone else’s property to tap their electricity, Cobb said.

“Even though I have a personal property right to put my trailer on there, I don’t have a personal property right to take your electricity,’’ Cobb said.

“It’s the same thing with water,’’ she said. “And the person next to me can’t get it because your well is going to go dry.’’

Borrelli said that’s what happening.

“What’s clear to me is that Arizona is the laughing stock of the world,’’ he said.

“Saudi farms are exploiting groundwater in my district,’’ Borrelli said.

That is a specific reference to land owned and leased by the state to a Saudi-owned firm to grow alfalfa that is shipped overseas to feed dairy cattle, as Saudi Arabia prohibits the growing of such a water-intensive crop.

“Obstructionists at the Capitol would rather choose the deepest pockets who can drill the deepest wells over everyday Arizona residents, farmers and ranchers,’’ Borrelli said.

He noted that Griffin was doing more than just bottling up his water bill — and previously those of Cobb when she was at the Capitol. He said Griffin is actively doing what she can outside of the Legislature to sideline any proposals.

“In fact, she has warned potential stakeholders not to engage with Mohave County on this issue,’’ he said.

Cobb said she does not understand why Griffin is so opposed to having each community — or each groundwater basin area — decide how best to handle its own problems.

“She will not take that at all,’’ Cobb said. “She said the way we have it is good enough and it doesn’t need to change.’’

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning