An outcome long held to be unthinkable for the Colorado River Basin — litigation — has entered the realm of the thinkable.

It may even be likely, in the face of continued river water shortfalls and irreconcilable conflicts between the Lower Basin states including Arizona and the Upper Basin states over how to fix them.

The clear possibility of lawsuits loomed large this past week at a public meeting in Phoenix. Top Arizona water officials made the case that the Upper Basin states are only three years away from the point where they're not sending enough water from Lake Powell downstream to Lake Mead to meet legal obligations set by the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

That — and the differences between the two basins over how to share the pain of water shortages — could spark court fights, an outcome that until now was seen as highly undesirable for many reasons. Not least, it's that a lawsuit would blow up and jeopardize a longstanding tradition of collaboration among the basin states. It would also drag out the conflicts over the Colorado almost indefinitely — as the river's supplies continue declining.

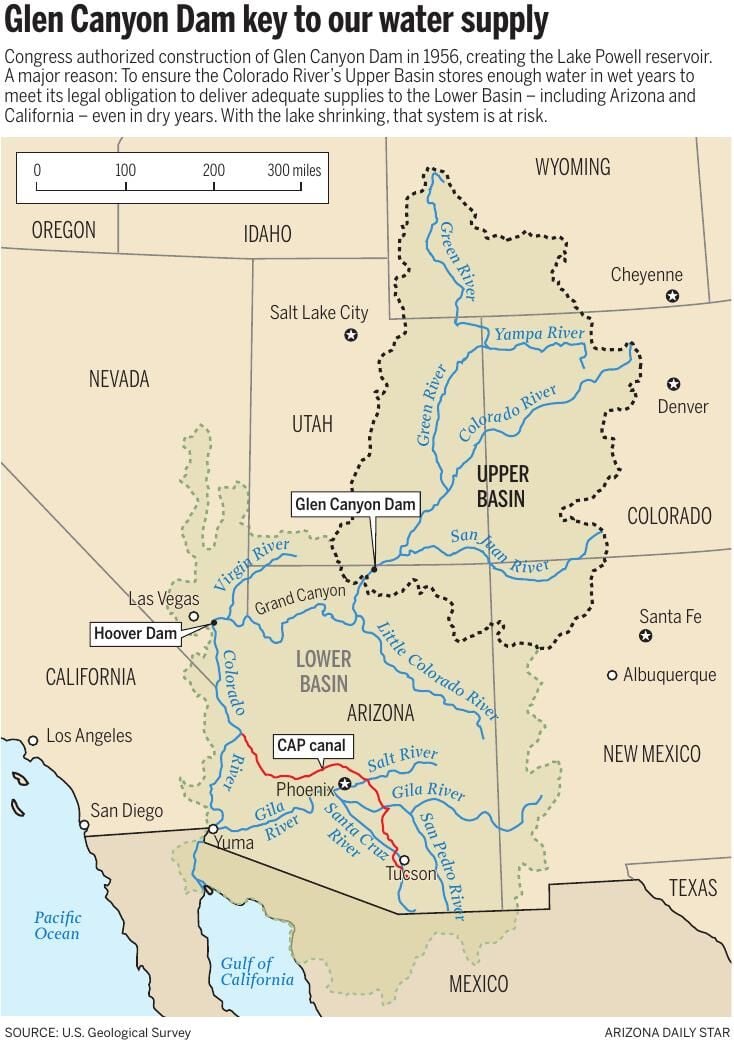

The 1922 compact divided the river's water rights between the two basins and set minimum requirements for how much Upper Basin states must send downriver to the Lower Basin states over 10-year periods. Arizona, Nevada and California are the Lower Basin states. Utah, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming make up the Upper Basin.

Litigation would be preceded by what water experts say is a "compact call," a never-used tactic in which Lower Basin states would demand that the Upper Basin reduce its water uses to bring releases in line with compact requirements.

"When you do a compact call, that is akin to dropping a bomb into the process," said David Wegner, a retired U.S. Bureau of Reclamation engineer who still works on water issues as a member of a National of Academy of Sciences Advisory Board.

The Colorado River flows through the Grand Canyon. Litigation between the river's Lower Basin states, including Arizona, and Upper Basin states may be likely, in the face of continued river water shortfalls and irreconcilable conflicts over how to fix them.

Both basins' officials agree the compact requires the Upper Basin states to deliver 75 million acre-feet of water to the Lower Basin over a decade. One big difference arises because the Lower Basin states also make the case — and the Upper Basin disagrees — that the Upper Basin states must make available another 750,000-acre feet annually over a decade to help satisfy U.S. obligations to deliver twice that much in that time to Mexico. The latter boosts the total delivery obligation to 8.25 million acre-feet — the equivalent of eight years' worth of Central Arizona Project deliveries to Arizona.

There is no provision in the 1922 compact for someone to make a compact call, said longtime water researcher and former Colorado regional water official Eric Kuhn. But the idea of such a call has evolved over the years to mean the Lower Basin states would demand the Upper Basin states curtail uses and deliver more water to the Lower Basin, Kuhn said.

"The Upper Division states would almost certainly say 'hell no!' The Lower Basin States would then go to court to ask the Supreme Court to force the Upper Division states to implement a compact call to deliver more water," Kuhn said.

At the meeting of water officials Monday in Phoenix, Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke said he doesn't want Arizona being "backed into a corner" and taking an unacceptable negotiated deal to avoid litigation.

At the same time, he said, "I do not want litigation. There is uncertainty with litigation. We see that in other basins, with judges running rivers. It's not good for anybody."

Nevada officials declined to comment on remarks by ADWR and Central Arizona Project officials about the possibility of going to court.

Water flows along the All-American Canal near Winterhaven, California. The canal conveys water from the Colorado River into the Imperial Valley. California officials are "united" with Arizona on the need to enforce the 1922 river compact.

But California's Colorado River Commissioner J.B. Hamby said California officials are "united" with Arizona on the need to enforce the compact's legal obligations if necessary.

And a number of local officials, including Tucson City Manager Tim Thomure, said they also would support Arizona's position if it comes to that.

"A compact call is the elephant in the room on the Colorado River," Hamby said. "The risk of conflict will only grow if the Upper Basin states fail to work in good faith with the Lower Basin to achieve basin-wide reductions and sustainable river management.

"Inaction places the entire Colorado River Basin at risk, including the risk of involuntary curtailments to Upper Basin water users," he continued. "These risks are far from hypothetical and have been known for decades — they could disrupt major metropolitan areas like Denver and provoke serious conflicts between senior agricultural users and junior urban users within the Upper Basin.

"The only viable path forward is compromise — anything less jeopardizes the future of the entire basin and Upper Basin water users," Hamby said.

"A giant chasm" in viewpoints

CAP General Manager Brenda Burman outlined serious concerns at Monday's meeting of the Arizona Reconsultation Committee.

Those concerns are that fairly soon, the Upper Basin won't meet its obligation, if annual releases from Lake Powell to Lake Mead stay at their current level of 7.48 million acre-feet until then.

"If it continues like this, the Upper Basin will be out of compliance, possibly as early as 2027," Burman said.

This is happening at the same time the two basins have been deadlocked for nearly nine months over competing proposals for reducing humans' take from the Colorado.

The Upper Basin proposal calls for the Lower Basin to take all the needed future cuts in water supplies. That's partly on the grounds that the Upper Basin currently uses far less river water every year than its annual legal share. The Lower Basin is using much less water than it used to, but it still uses significantly more water than the Upper Basin, and when evaporation is considered, it uses more water than its 1922 compact allocation.

The Lower Basin proposal says it will swallow the first 1.5 million acre-feet of cuts needed to eliminate its long-standing structural deficit between water use and supplies.

But if more cuts are needed, its proposal would split them equally between the basins. The Lower Basin states argue that it's not fair to ask them to bear the entire burden of bringing the depleted river into balance.

At Monday's meeting, Burman said that under the Lower Basin proposal, the Upper Basin's share of cuts would be much less than the cuts it would have to take if the Lower Basin states sued to force the Upper Basin into complying with the compact.

"I hope this underlines why we believe the Lower Basin alternative is a compromise," Burman said.

So far, the Upper Basin has only offered to make "voluntary, compensated reductions in water use," but those reductions wouldn't have any certainty and would be pretty small in size, said ADWR Director Buschatzke.

The Upper Basin states also want to eventually "grow" their water use by building additional projects to store and/or divert river water, without regard to their river compact obligations, he said.

"This is a visceral issue. There's a giant chasm" between the two basins on that point, he said, "and it is a bottom line for all three of us (Lower Basin states)."

"Disappointed" with Arizona

Responding, Becky Mitchell, Colorado River commissioner for the state of Colorado, said, "It is disappointing that Arizona is considering destabilizing litigation in the Colorado River Basin. It appears to be in an effort to avoid reducing their uses in sufficient amounts to stabilize the system in a drier future.

"The Upper Division States have fully complied with the Colorado River Compact, and use millions of acre-feet less than our apportionment every year," said Mitchell, in a written statement.

That's due to what she called "strict administration of water rights" and regular water shortages on tributaries to the river in the Upper Basin from which farmers draw their water.

"The Upper Division States’ alternative suggests that the Lower Basin water users should also take steps to live within the available supply, as Upper Basin water users have done for years," Mitchell wrote.

"Colorado is committed to working with the other basin states, the tribal nations, and the Bureau of Reclamation towards collaborative and sustainable solutions on the Colorado River. We are prepared to defend Colorado’s significant interests in the Colorado River.

"But I believe that the best outcomes, particularly for Arizona and the other Lower Basin States, happen when the states negotiate together," Mitchell said. "This moment makes it clear that the status quo is not working. We cannot continue the demand-based management of Lakes Powell and Mead. We must move to a supply-based framework where actual water supplies mean the entire Colorado River Basin is living within the means of the river."

"50/50" who would win

Legal experts are split over the Lower Basin's chances of winning in court over the compact.

Kuhn said, "I'd say it's 50/50 as to which side has the better case, but it's a certainty that such a case would take years for the court to make an actual decision."

Sarah Porter, director of Arizona State University's Kyl Center for Water Policy, said she believes the "Lower Basin has a pretty strong case" if water releases drop below 8.25 million acre-feet annually over 10 years.

The Upper Basin states and their legal supporters note the compact required them not to "deplete" the river's flow below that level. They say that requirement doesn't apply when the depletion is caused by climate change.

But nothing in the compact appears to make an exception for something like climate change, Porter said. Officials did contemplate a long-term drought back in 1922, and "there was an understanding that weather was super unpredictable and the risks were allocated," she said.

As for the Upper Basin's obligation to Mexico, ASU law Professor Rhett Larson noted that the 1968 law that authorized construction of the CAP's canal system makes it explicit that the Upper Basin has an obligation to Mexico. The law makes it a “national obligation” to satisfy Mexico’s water right to the Colorado River under a 1944 treaty.

"A national obligation is hardly national if it applies only to some of the states, or to one basin," Larson said.

But University of Colorado law Professor Mark Squillace said he suspects Lower Basin state officials understand that suing to enforce an alleged compact violation "opens a can of worms that would be better off left closed."

If the Lower Basin were to sue, the Upper Basin might well choose to defend itself on the grounds that the 1922 compact is void, as a matter of contract law, at least as to its water allocation "because it was based upon a fundamental mistake of fact," he said.

"That mistake, of course, was the assumption that the river would produce on average about 16.9 million acre-feet, which was roughly the amount that was being produced during the period that preceded the compact," he said.

It's been far less and is now down to about 12 million. The Lower Basin's claim of being entitled to 8.25 million acre-feet a year would leave the Upper Basin with something less than 4 million a year.

"Whatever one thinks of the compact, this is surely not what the drafters intended," Squillace said.

This case could go several different ways, "but I think the federal government would get involved before it turns into a bloodbath between the states," said Wegner.

ASU water researcher Kathryn Sorensen, however, said the amount of water over which the basins are fighting — up to 4 million acre-feet in potential annual cutbacks — may be too big to be settled through collaboration.

"I desperately hope someone pulls a rabbit out of the hat," Sorenson said.

"With 2 million acre-feet, you may be able to find the right package of wins and losses and tradeoff. At 4 million, those tradeoffs become so enormous, so obstructive, at that point, you might as well play this out and see who wins. What are you left with? You go to the mat."

Tony Davis graduated from Northwestern University and started at the Arizona Daily Star in 1997. He has mostly covered environmental stories since 2005, focusing on water supplies, climate change, the Rosemont Mine and the endangered jaguar. Tony and David talk about the award winning journalism Tony has worked on, his journey into journalism, Arizona environmental issues and how covering the beat comes with both rewards and struggles. Video by Pascal Albright/Arizona Daily Star

Tony Davis graduated from Northwestern University and started at the Arizona Daily Star in 1997. He has mostly covered environmental stories since 2005, focusing on water supplies, climate change, the Rosemont Mine and the endangered jaguar. Tony and David talk about the award winning journalism Tony has worked on, his journey into journalism, Arizona environmental issues and how covering the beat comes with both rewards and struggles. Video by Pascal Albright/Arizona Daily Star

Tony Davis graduated from Northwestern University and started at the Arizona Daily Star in 1997. He has mostly covered environmental stories since 2005, focusing on water supplies, climate change, the Rosemont Mine and the endangered jaguar. Tony and David talk about the award winning journalism Tony has worked on, his journey into journalism, Arizona environmental issues and how covering the beat comes with both rewards and struggles. Video by Pascal Albright/Arizona Daily Star