Tumamoc Hill is one of Tucson’s most popular outdoor destinations, and not just for humans.

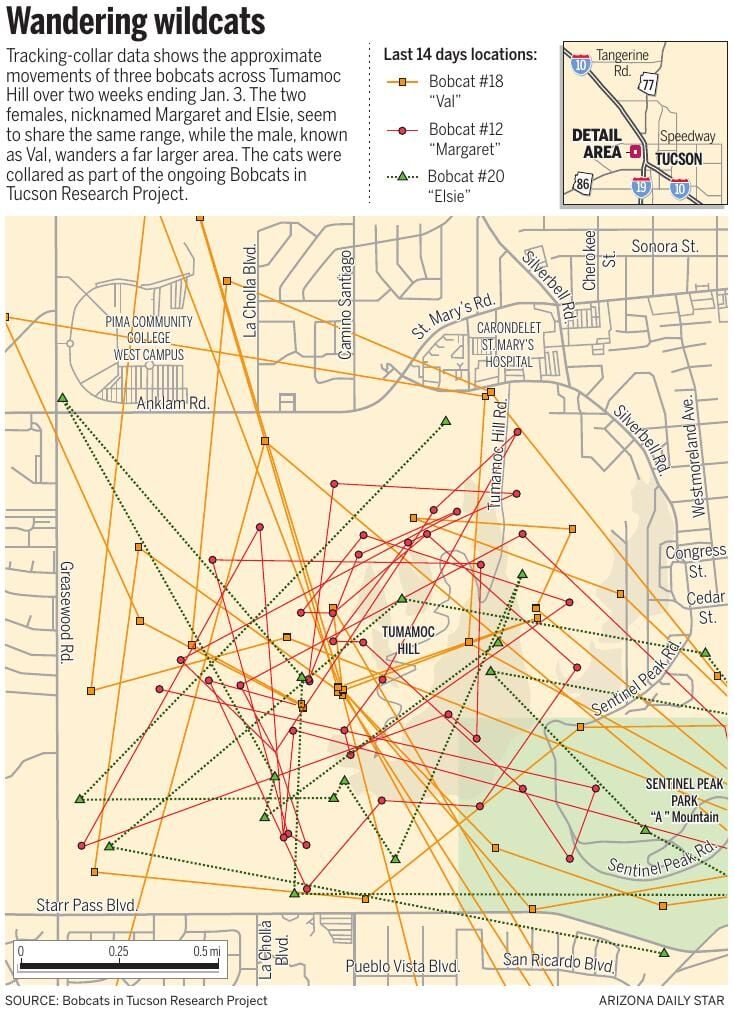

Researchers are tracking three bobcats that crisscross the hill regularly, including a surprising pair of females that appear to be peacefully sharing the same home range.

“There’s an incredible density right there,” said wildlife biologist Cheryl Mollohan, lead investigator for the aptly named Bobcats in Tucson Research Project.

The study team currently has 11 of the usually solitary animals fitted with tracking devices on the east side of the Tucson Mountains, with plans to capture and collar eight more bobcats in the coming weeks.

Since the first cat was collared in November 2020, researchers have logged 18 different individuals at more than 8,000 locations from 36th Street north to El Camino Del Cerro and as far east as the Santa Cruz River, just across Interstate 10 from downtown. That includes at least four cats regularly tracked on Tumamoc Hill, Sentinel Peak and the surrounding neighborhood.

“They move all the time,” said Kerry Baldwin, a retired Arizona Game and Fish Department biologist who now serves as project coordinator for the study. “They’re really always on the move.”

According to the data collected so far, male bobcats in the Tucson Mountains tend to have larger home ranges that overlap with those of other cats, while the females maintain smaller, more distinct territories.

The one big exception is on Tumamoc, where two females, nicknamed Margaret and Elsie, seem content to coexist, at least for the time being.

Dr. Ericka Johnson, a veterinarian from Tucson’s Arizona Exotic Animal Hospital, monitors a sedated bobcat that was just fitted with a tracking collar as part of a study in the Tucson Mountains. The male cat, nicknamed Val, was caught and released from the yard of a home just off Sentinel Peak Road on Nov. 13 and continues to roam on and around Tumamoc Hill.

The two cats don’t just share nearly identical home ranges, Mollohan said. They have actually been pinpointed in the same location at the same time.

She suspects they are blood relatives — probably a mother and a daughter — but she doesn’t have the DNA results yet to prove it.

Surprises so far

The goal of the three-year study is to better understand the biology and behavior of what could be the highest concentration of urban bobcats anywhere in the United States.

Researchers hope to learn more about where Tucson-area wildcats hunt, rest, give birth and raise their kittens — information that could help reduce conflicts with humans and increase appreciation for the animals living among us.

“There just hasn’t been much of this sort of work done,” Mollohan said.

Already, the team has encountered a few surprises.

Mollohan said she expected to see at least a few of their city-dwelling cats set up dens and give birth on the flat roofs of houses or in the residential backyards some of them frequent. Instead, they literally headed for the hills.

“Those females moved away from the neighborhoods and went to the steepest, highest, least accessible areas to have their babies,” she said.

Margaret, for example, made her den in a rock pile near the observatory on top of Tumamoc, far from the hill’s heavily traveled hiking trails.

Baldwin said he has been surprised by how “seamlessly” the cats move through the suburban landscape. He thought the data would reveal narrow and obvious travel corridors. But while there do seem to be some preferred routes, the animals show little sign of being hemmed in by the encroaching city.

“I think it really demonstrates what you can do with some green spaces,” Baldwin said. “And those spaces don’t have to be all that large,” especially when they remain connected by washes and other natural corridors.

A bobcat mother nurses her kitten in a Tucson backyard, as seen in a photo taken by a wildlife camera on July 2, 2021.

Danger city

The study team is also learning more about the threats that bobcats face in urban settings.

The project has lost six of its collared cats since the first traps were set in November 2020.

Three were hit by cars, one was shot by a Menlo Park homeowner after feeding on the man’s chickens, and one was found mutilated and partially buried in a way that could only have been done by human hands, Mollohan said.

The sixth fatality involved a male bobcat that died mysteriously within a day of being fitted with a collar.

Mollohan said they conducted a necropsy on the animal but found no clear cause of death. The stress of being caught in a trap, then drugged and handled by humans could be to blame — a rare but regrettable outcome wildlife biologists refer to as “capture myopathy.”

“We just don’t know,” Mollohan said.

The research project was launched with a $33,000 grant from the Game and Fish Department’s Heritage Fund, which uses Arizona Lottery proceeds to pay for conservation work around the state. Since then, private donors have contributed roughly $30,000 more, enough to buy nine more tracking collars and refurbish some of the older ones.

The batteries on the collars tend to last for 18 months to two years, depending on how much data the tracking devices are collecting.

The researchers can reprogram the collars remotely and send a signal to make them open up and fall off if need be. The collars are also designed to release on their own just before their batteries die.

“The technology is pretty amazing,” Baldwin said.

Safe at homes

The test subjects are not being tracked in real time. Instead, the data is compiled and sent to the team in an email every few days, though the collars will send out a so-called “mortality alert” if a cat stops moving entirely for four hours or more.

Mollohan said she initially set the alert to go off after two hours, but she decided to increase it when a cat they feared was dead turned out to be taking a long nap in the grass at an elementary school off Greasewood Road.

Eventually, she said, they hope to catch and collar every adult female bobcat in their roughly 24-square-mile study area because the females are responsible for all of the child rearing.

The females collared so far began welcoming their first litters of kittens in late March, with varying degrees of success.

The researchers struggled to pinpoint the locations of the den sites at first, but a pattern emerged when they reprogrammed the tracking collars to collect locations every two hours instead of every six hours or so.

With the additional data, seemingly random movements began to look more like a starburst or an asterisk — a bunch of lines moving out and back from a central point, as the mother left her hidden kittens and then returned.

Now that they have a better idea of when to expect the year’s first batch of kittens — sometime between the end of March and the middle of April — they should be able to closely monitor the cats’ denning and child-rearing behavior this time around, Mollohan said.

Based on what they’ve seen so far in the study area and elsewhere in Tucson, she said some female bobcats seem to treat residential backyards as their own personal day care centers.

Once their kittens get large and mobile enough to wander away from the birth den, the mother will try to find a new place to stash them. Occasionally, she will choose the walled yard of a house, where the kittens are contained and relatively safe from predators.

A bobcat nicknamed Elsie recovers from sedation in a cage after being fitted with a tracking collar in November as part of a research study in the Tucson Mountains. Elsie is one of two collared female bobcats that lives on and around Tumamoc Hill.

A male bobcat sits in a trap in a yard near "A" Mountain after being captured as part of a study on Nov. 13. The cat, nicknamed Val, was fitted with a tracking collar and set free.

A female bobcat, nicknamed Margaret, sits in a trap after being captured in the Tucson Mountains on Nov. 30 as part of a study. Tracking data shows Margaret spends most of her time in the area between Tumamoc Hill and Santa Cruz River Park.

Such urban bobcat families have been known to spend weeks or even months at Tucson homes that prove welcoming enough.

“We have one homeowner in Vail who just gives up his backyard all summer to the cats,” said Al LeCount, a wildlife biologist with the research team.

Valerie and Val

Ultimately, Mollohan hopes to learn more about why the cats pick certain houses and, in some cases, return to them year after year.

To help with that, the team set up a website — bobcatsintucson.net — to collect bobcat sightings throughout the community, not just in the Tucson Mountains study area.

More than 725 bobcat reports have been submitted so far, including a few in the heart of the city, but researchers want more people to participate so they can fill in some blank spots on the Tucson map. For example, Mollohan thinks the area north and west of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base is seriously underreported.

Such information will help the team identify more homes that are regularly visited by bobcats and pick out future candidates for tracking collars.

That’s how one of Andrew and Valerie Greenhill’s neighborhood bobcats joined the study in November.

After the Greenhills submitted a photo to the project website of a very pregnant Margaret lounging in their backyard at the base of “A” Mountain in early April, the research team decided to set up a trap at the house so they could replace the cat’s aging tracking device.

They ended up catching a male bobcat instead.

Since then, the cat nicknamed Val has bounced all around Tumamoc Hill and ventured as far south as Kennedy Park.

The research team is a little worried about all his wandering. So is Valerie Greenhill.

“Val needs to slow his roll,” she said. “He’s taking some extreme risks with the streets that he’s crossing.”

Mollohan said the Greenhills’ welcoming attitude toward the wildlife around them is typical of a lot of Tucsonans she meets. She thinks it’s a key reason why bobcats tend to fare so well here.

If anything, Valerie Greenhill seems eager for even more wildcat encounters.

“We’ve never had one come hang out for days on end” or bring its kittens along, she said. “We’ve never lucked out to that degree. They’re gorgeous creatures.”

Three bobcats were filmed Jan. 2 passing through the back yard of a home in the Catalina Foothills just before sunset.

Jennifer Perez, who recorded the video of the feline trio and shared it on social media, said she often sees wildlife enter her yard from a deep wash located behind it. One bobcat shown can be heard softly growling around 30 seconds into the video. Video courtesy of Jennifer Perez.