Under the east grandstands of Arizona Stadium, University of Arizona scientists have been working for nearly 20 years to make huge mirrors for the world’s most powerful optical telescope.

And though the Giant Magellan Telescope is still years away from completion in Chile, the project has become a mainstay for the UA’s top-ranked Department of Astronomy and Steward Observatory and its world-renowned Richard F. Caris Mirror Laboratory.

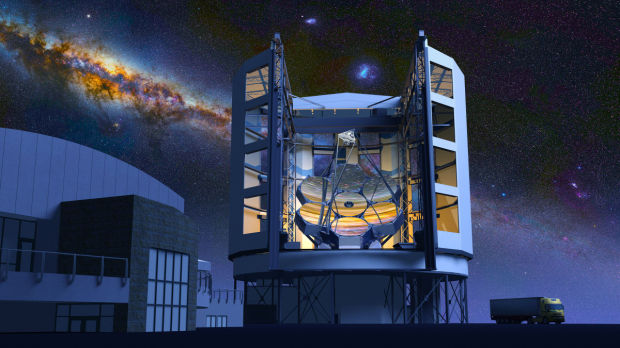

When completed around the end of the decade, the telescope known as the GMT will be the world’s most powerful land-based telescope, though some other telescopes in development could rival it in size.

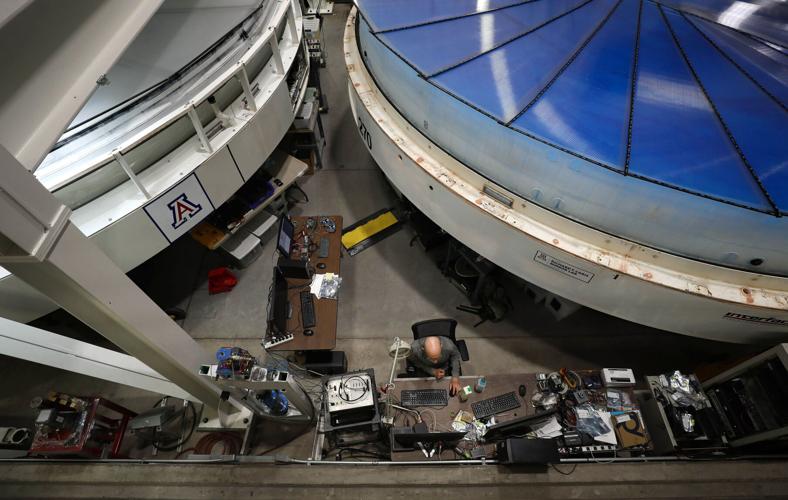

Bill Sisk, an electrical engineer, works at his desk in the room where they grind and polish molded mirrors at the University of Arizona Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab on Aug. 2.

With a light-gathering surface 25.4 meters or more than 83 feet wide, the GMT is expected to render images up to 10 times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope and four times sharper than the James E. Webb Space Telescope, allowing astronomers to peer further into space than ever before.

The UA is not only a founding partner in the Giant Magellan Telescope — the telescope would not exist if it weren’t for the school’s world-leading expertise, said Robert Shelton, a former UA president who has headed the telescope project as president of the GMTO Corp. since 2017.

Shelton said not only is the Caris Mirror Lab the only lab capable of making the GMT’s seven 8.4-meter-wide main reflector mirrors, but the UA scientists had to develop a process to grind and polish them to slightly asymmetrical, or off-axis, dimensions to make the GMT work.

“In many ways, the University of Arizona was the birthplace of the Giant Magellan Telescope, because they had to show that you could make these mirrors and make them with the off-axis configuration that had never done before — it’s the only place in the world you can make these mirrors,” said Shelton, a physicist who was president of the UA from 2006 to 2011.

Astronomical impact

The giant telescope also has had an outsized economic impact for the UA, a founding partner of the telescope project since its inception in 2004.

The UA has won about $100 million in contracts for mirror fabrication and other Giant Magellan Telescope work, and by the time the project is done it expects to have at least $250 million in contracts, said Buell Jannuzi, director of Steward Observatory and head of the UA’s Department of Astronomy since 2012.

Besides the mirror lab, UA astronomers are involved in the GMT’s adaptive optics design and some of the six planned optical and infrared instruments planned for the telescope.

Shelton said the Giant Magellan Telescope Organization has raised commitments for about $850 million of total project costs expected to reach about $2.5 billion by the time the telescope is completed and installed at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

In August 2022, the GMT announced $205 million in new funding commitments from its international consortium, including leading contributions from founding partners including the UA, the Carnegie Institution for Science, Harvard University, the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Chicago.

As a project partner, the UA has so far contributed $100.6 million of $142.8 million it has committed to raising for the GMT, which includes a $50 million commitment as part of the partners’ funding round last summer, Jannuzi said.

Overall, the UA’s astronomy and space sciences programs — including the Steward Observatory and the mirror lab, the Lunar and Planetary Lab, the Department of Astronomy and the Department of Planetary Sciences — generate $560.5 million in economic activity annually or nearly as much as the 2022 Super Bowl in Phoenix, according to a report issued by the UA in March.

That includes $252.9 million in direct impact from spending and 1,176 direct jobs, along with indirect and induced jobs and economic activity, according to a study by Rounds Consulting Group.

Buell Jannuzi, director of the Steward Observatory and head of the Department of Astronomy at the University of Arizona, talks about the process of constructing the Giant Magellan Telescope, for which the UA lab cast and polished six of seven giant reflector mirrors.

Years long project

While it’s been a long road for the Giant Magellan Telescope and a long road lies ahead, work continues apace at the UA mirror lab and contractor sites around the world.

Work on the GMT’s foundation is underway on a steep ridge at an altitude of 8,500 feet on Cerro Las Campanas, where the GMT will join the twin, 6.5-meter Magellan Telescopes operated since 2002 by a consortium including the Carnegie Institution for Science, the UA, Harvard, the University of Michigan and MIT. The UA mirror lab made the mirrors for the original Magellan scopes.

The GMT’s secondary mirrors, which gather light from the big primary reflectors, are being made in Italy and France, Shelton said.

Those mirrors, smaller and much thinner than the primary mirrors made at the UA, will be deformable in shape to allow astronomers to adjust for image aberrations caused by the Earth’s atmosphere.

The 12-story telescope’s massive, 2,000-ton base is under construction by contractor Ingersoll Machine Tools in a purpose-built plant in Rockford, Illinois.

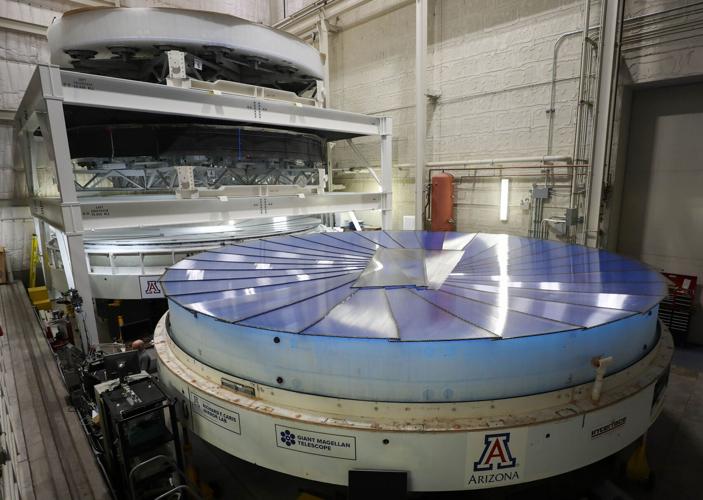

At the UA mirror lab in Tucson, scientists have now completed three of the GMT’s seven primary mirrors, using a giant, rotating furnace invented by UA regents professor Roger Angel and colleagues at the UA in the 1980s.

The lab, where about 35 to 45 people work with support of about 200 others on campus, is in the process of polishing three other mirrors and plans to cast the seventh and final mirror in October, Jannuzi said.

Painstaking precision

The roughly four-year process to make a single mirror is painstaking, to say the least.

It takes about 14 months to complete a mirror casting, which starts with creating a mold with a honeycombed back to create a strong yet lightweight mirror.

Technicians then load 20 tons of pure, borosilicate glass blocks into the lab’s giant furnace for spin-casting at temperatures topping 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. After, the temperature is lowered for a monthlong annealing process

Once a mirror blank is finished, an array of fingerlike supports is attached to the back to support the glass during a grinding and polishing process that takes two to three years — with precision testing every step of the way.

The Giant Magellan telescope pieces at the University of Arizona Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab.3.

“You polish for maybe 60 to 80 hours, make measurements of the surface and then you polish again,” Buell said during a recent tour of the Caris lab.

“If you remove too much glass in one spot, you have to bring the whole surface down to that, there’s no way to add. It’s a conservative process like we were cutting marble or something, if you take off too much marble, you can’t put it back on.”

The mirror surface is polished to an optical surface precision of less than one thousandth of the width of a human hair — or five times smaller than a single coronavirus particle.

Once the polishing is completed, the glass is coated with a thin layer of aluminum to form a reflective surface.

Though the Giant Magellan Telescope is the UA Mirror Lab’s biggest current project, it has continued to make large mirrors for other telescope projects.

Besides the twin Magellan scopes, those include twin, 8.4-meter mirrors made for the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham, which went into full operation in 2008, and an 8.4-meter mirror for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (originally called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope) expected to go into operation in Chile in 2024.

The mirror lab also has made several 6.5-meter mirrors for various projects, recently including a space-based telescope; in all, the Caris Lab has cast 23 mirrors since 1985.

Top-ranked programs

Jannuzi said that Steward Observatory acts more like a national lab than an academic institution, adding that most of the mirror lab’s employees are non-academic.

But because of facilities like the mirror lab, UA students benefit from the school’s astronomy and space sciences programs that are considered among the best in the world for both research and education, he said.

The UA ranked No. 1 in 2021 for astronomy and astrophysics research expenditures at more than $113 million, according to the National Science Foundation.

And the UA’s space sciences program, including astronomy, ranks No. 10 overall, No. 6 in the U.S. and No. 2 among public universities in the latest U.S. News & World Report Global Universities rankings.

“We have one of the largest undergraduate major programs in the country, and it’s growing rapidly, we had a record year last year, and we have one of the largest graduate programs in the country,” Jannuzi said.

“We have 81 Ph.D.s currently in one department or another, working with our faculty just in astronomy, not even counting planetary science,” he said. “Most of these people end up in academia but not all — a lot of them go to (companies like) Lockheed or Raytheon, or even into the life sciences.”

The Giant Magellan Telescope, seen in this rendering, will be constructed at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

Milestone review

The Giant Magellan Telescope Organization reached a key milestone recently when the project passed a critical preliminary design review by the NSF, which the GMT partners hope will fund much of the rest of the telescope project.

“That review was actually held in two big sessions, in December and in February and then we just recently got the written report and it’s very, very favorable,” Jannuzi said. “The review committee recommended that we move into what’s called the construction queue.

“It’s a huge step, it’s passing all the technical (requirements). They basically are saying, ‘OK, technically you’re ready to go. You’ve had your management in place, you have the structures in place.’”

He said the hope is that the National Science Board, which approves major NSF grants, and the government will agree the project is ready for funding in 2026.

The GMT won a $17.5 million grant from the NSF in 2020.

“Right now the problem is, that’s later than we had originally planned, and so if you want the cost to stay at the current cost, we need to raise some money now because things are in progress,” Jannuzi said.

Shelton said though the plan is to have all seven primary GMT mirrors installed by 2031, researchers will be able to start observations and testing before that with four secondary mirrors and three primary mirrors installed.

Whether the GMT becomes the world’s biggest ground-based optical telescope will depend on when it goes into operation relative to other large projects, including the European Southern Observatory’s 39.5-meter Extremely Large Telescope, under construction in Chile and projected to see “first light” in 2028.

Finding funding

The GMT got a major boost in 2021, when the 2020 U.S. Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics named the U.S. Extremely Large Telescope Program at the top of its list of priorities for ground-based astronomy.

The U.S. Extremely Large Telescope Program is a joint effort of the GMT, the Thirty Meter Telescope planned for Hawaii and NOIRLab, (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), an NSF-sponsored research center for ground-based, nighttime optical and infrared astronomy resulting from a 2019 management merger of national observatories, including Kitt Peak near Tucson.

NOIRLab, whish is headquartered on the UA campus, is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy Inc.

Meanwhile, the total projected cost of the GMT has grown from $1.5 billion to closer to $2.5 billion, Shelton said, adding that the organization has spent about $500 million so far.

After raising nearly half the project cost privately to prove out the technology, Shelton said the GMT has a good argument to win federal funding for the rest of the cost, citing projects including the Hubble and Webb space telescopes that were completely funded by taxpayer dollars.

The Webb cost NASA nearly $10 billion to build and launch.

In the fiscal year 2023 omnibus appropriations bill signed into law in January, Congress directed the NSF to provide $30 million to support the design and development of the next generation astronomy facilities, but that money has not been budgeted, according to the American Astronomical Society.

“In those cases, the federal government paid for everything,” Shelton said. “So, now thanks to the founders, thanks to the University of Arizona, we’re bringing half of that money to the table, and that money, just from the business perspective, that money went in early to reduce these risks.

“It’s like any startup company, whose production risks are heavy early on,” he continued. “The risk of not being able to polish that off-axis mirror — that risk was retired because of the funds that the founders gave and the brilliance of the Mirror Lab, and that’s been repeated over and over again to show that we can do this.”