The Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union 30 years ago last December, but Tucson never stopped being a target.

Now the Russian invasion of Ukraine is stoking fresh fears of an all-out nuclear conflict that could wipe the Old Pueblo off the map, according to a new analysis by a former war planner for the U.S. Strategic Command.

From 2002 until 2010, David Teter worked at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, where he contributed to the nation’s strategic plans for nuclear war as an analyst and “vulnerability engineer.”

By then, Teter said, work on the so-called Red Integrated Strategic Offensive Plan, or RISOP, was winding down, as Strategic Command and the Defense Intelligence Agency shifted focus to global terrorism and other more looming threats.

But he never stopped thinking about nuclear war, even after he left national security work.

“I know how these weapons work and how you might employ them,” the San Francisco-based engineer and private consultant said.

During his free time over the past several years, Teter has been building publicly available, open-sourced attack scenarios like the ones he used to help write for the government, using information readily available on the internet — nothing top secret or even sensitive.

A Titan II missile is lowered into a silo, possibly near Three Points in December 1962. The warhead and fuel were added later. The hardened intercontinental ballistic missile sites ringed Tucson from the early 1960s until decommissioning in the 1980s.

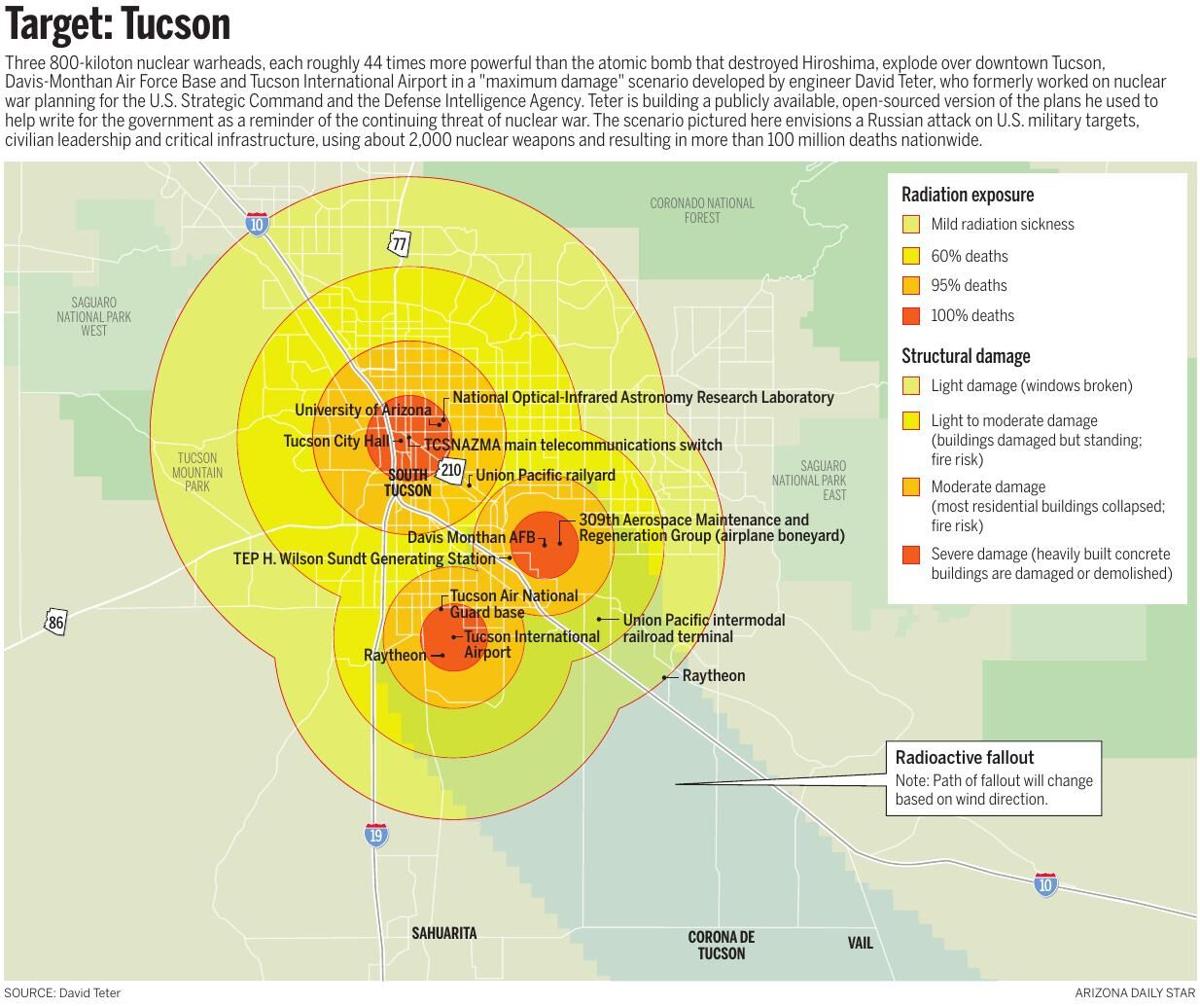

The worst attack he simulated involves about 2,000 nuclear weapons targeted to inflict “maximum damage” on the United States.

He estimates that such a strike could kill more than 100 million Americans and destroy the nation’s transportation, communication, power, water and manufacturing capabilities.

Maximum damage

In Arizona, the Palo Verde nuclear power plant and Hoover, Glen Canyon and Roosevelt dams would all be hit. So would Kingman, Flagstaff, Pinal Airpark, the Asarco mine and smelter in Hayden and the Marine Corps Air Station in Yuma.

Teter has two warheads hitting Sierra Vista — one at Libby Army Airfield and the other at Fort Huachuca itself. The greater Phoenix metro area gets slammed with a whopping 18 nuclear blasts.

He targets Tucson with three 800-kiloton nuclear warheads, each roughly 44 times more powerful than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

Two would explode at ground level at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Tucson International Airport. An airburst would take out the third Tucson target: a central communications hub known as an electronic switching system, or ESS, which is housed in a drab office building across Alameda Street from Tucson City Court.

The building is easy enough to spot. It’s the one with the enormous, red and white communications tower jutting from the top of it along Scott Avenue. Inside the building is one of the roughly 100 ESS switches across the U.S. that help maintain communications nationwide, Teter said. “Very, very important equipment.”

The same warhead that would silence the phones would also vaporize or crush virtually all of downtown and the University of Arizona campus.

It was no small task to keep a huge fleet of Strategic Air Command B-47 bombers flying at Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson. What it took for one plane in 1959: Row 1: Bomber’s three-man flight crew. Row 2: Crew chief and two assistants. Row 3: Maintenance supervisors, support personnel and quality control inspectors. Remaining rows: Field maintenance techs, personnel from the Armament and Electronics Squadron and Aviation Depot Squadron personnel.

Coming in hot

Sorry if this isn’t the kind of breezy, fun reading material you might have been looking for on a Sunday morning, but that’s sort of the point.

Teter said he produced these new attack scenarios not out of fatalism, but as a reminder. “I think people have forgotten about this threat,” he said.

Teter is also hoping for a bit of closure. As he explained on Twitter recently, he’d much rather be talking about cats or gardening or medium-format film photography.

“I am posting this nuke stuff so that I can hand it off and get it out of my system,” he wrote.

Assisting him with the effort are self-described “security dude” Phil Moyer and Ivan Stepanov, a simulation engineer and physicist who is developing his own online nuclear war simulator.

Teter released the first maps of his simulated nuclear strikes in December, never realizing how relevant they would soon become.

Late last month, three days into the invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin placed his country’s nuclear forces on high alert in response to tough economic sanctions from the West and what he called “aggressive statements” by NATO.

A U2 high-altitude surveillance plane stationed at Davis-Monthan flies over the Tucson area in July 1986. The planes regularly flew over Soviet territory.

Though Teter’s scenarios all simulate Russian attacks on the U.S., he said they are not meant to demonize the Russian government or make the Russian people out to be our enemy.

“It’s a snapshot of a possibility. That’s all,” Teter said, though he acknowledged that the timing is suddenly lousy.

“Me posting these laydown maps isn’t helping with anyone’s anxiety,” he said.

Long-time target

Being in the crosshairs is nothing new for Tucson.

The city was an inviting nuclear target almost from the start of the Cold War. Davis-Monthan and the defense industry saw to that.

Historian Jason Gart from the Maryland-based research firm History Associates Inc. said that after World War II, there was a push to insulate the nation’s defense contractors from attack by moving them inland from the coasts and away from the major cities where many of them were concentrated.

“Hughes Aircraft was dispersed to Tucson,” said Gart, who wrote about the Cold War-era defense buildup in Arizona for his doctoral dissertation at Arizona State University. “They were looking for a place that was in the middle of nowhere.”

The missile factory Hughes opened in Tucson in 1951 almost certainly got the Soviets’ attention, Gart said. And if it didn’t, the Titan missile silos announced by the Air Force nine years later undoubtedly did.

By 1963, Tucson was surrounded by 18 of the underground facilities, each capable of launching an intercontinental ballistic missile in less than an hour and hitting a target almost anywhere in the Soviet Union with a nuclear warhead 600 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb.

The sites were developed over the opposition of a local group calling itself the Committee Against Ringing Tucson with Titans.

Its founder, UA physicist and meteorologist James E. McDonald, warned that prevailing winds would carry radioactive fallout to the city in the event of an attack on the silos. As McDonald told the City Council in May 1960, “Statements that the Titan will mean no increase in danger to Tucson are simply not supported by the facts.”

Another potential target landed in Tucson in the mid-1960s, when Davis-Monthan became a base for global operations by U-2 spy planes.

John Stufflebean and family in their fallout shelter in a Tucson neighborhood in April 1961.

Nuclear destruction remained a concern in 1981, when then-Pima County Supervisor David Yetman described Tucson’s necklace of Titan missile sites as “a magnet of death.”

He said plans to evacuate the city in the event of an attack were “utter wishful thinking,” and he called on the Defense Department to either provide the community with adequate fallout shelters or remove the silos altogether.

By then, the aging Titans were already on their way out.

The Air Force began decommissioning the land-based ICMBs in 1982, and the last silo in Southern Arizona shut down in 1984, though Davis-Monthan continued to serve as training base for ground-launched cruise missiles until 1990.

The lone remaining Titan II silo is now a National Historic Landmark, open for tours in Sahuarita, roughly 25 miles south of Tucson as the fallout flies.

Give me shelter

Present-day Pima County does not have “a nuclear bomb plan per se,” said county spokesman Mark Evans.

In the event of an attack, officials would refer instead to the Pima County Emergency Response Plan, which Evans described as “our guiding document for all emergencies.”

The response plan was last reviewed and updated in 2020, and covers such “human-caused hazards” as weapons of mass destruction and radiological or nuclear material releases.

No specific bomb shelters are identified in the document, but it does outline shelter capacity throughout the county.

“Any further actions we would take as a county would be at the direction of national and state emergency response agencies,” Evans said by email. “We would also refer people before and after the strike — assuming any of us in the county are still alive — to ready.gov’s page about nuclear preparedness.”

Sandra Espinoza, operations manager for the county’s Office of Emergency Management, said there is no one left in her department who knows the history of the county’s Civil Defense network or what became of things like fallout shelters and nuclear attack drills.

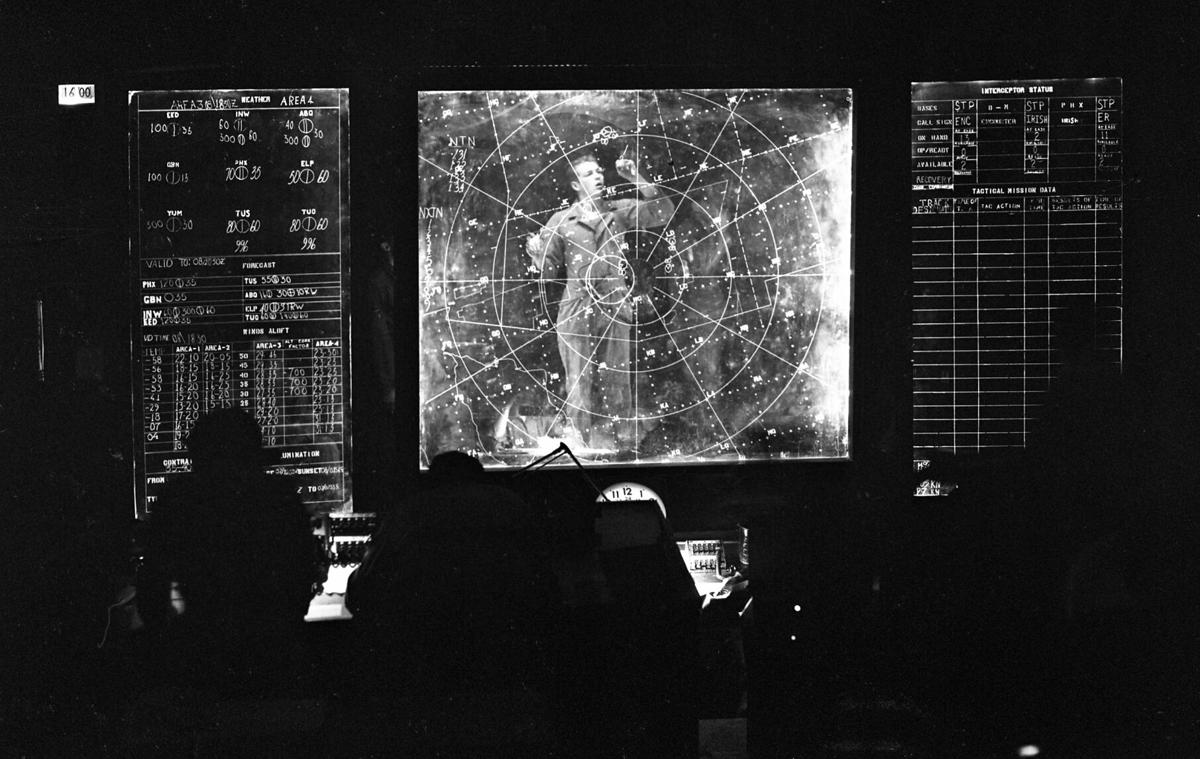

A 360-degree view of the command center at the Titan Missile Museum, 1580 W. Duval Mine Road, in Green Valley. The museum is a decommissioned site open for tours.

“Staff that served in this timeframe or knew of its existence have since long retired,” she said in an email.

But the specter of nuclear Armageddon lingers on.

In January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists set its famous Doomsday Clock to 100 seconds before midnight for the third year in a row, the closest it has been to civilization-ending apocalypse since the group unveiled the clock in 1947 to measure the threat of nuclear war.

And that was before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Teter hopes his attack scenarios serve as a wake-up call.

“The point of this exercise wasn’t to scare anyone, but for people to take the threat of nuclear war seriously,” he said.

It may be unthinkable, but that doesn’t mean we can afford to stop thinking about it.

Photos: Decommissioned Titan II Missile complexes around Tucson

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

The first Titan base near Tucson is fortified with concrete in May, 1961, as workmen continuously pour around the clock. Huge buckets of concrete are swung by a crane to the top of the structure where the material is poured into the hole through pipes in a slipform operation.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

A Titan Missile complex under construction near Rillito, Ariz. north of Tucson in 1961 (note cement plant in background).

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Thousands of feet of heavy duty reinforcing bar are tied together to form the backbone for tons of concrete to be poured for missile silo at this Titan Missile site under construction near Tucson in 1961.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

A worker inspects the ventilation tubes extended from the hardened silo during construction near Tucson in 1961.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Workers in the nearly-completed Titan Missile Site 11 silo near Tucson in 1961.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

The first Titan base near Tucson is fortified with concrete in May, 1961, as workmen continuously pour around the clock. Huge buckets of concrete are swung by a crane to the top of the structure where the material is poured into the hole through pipes in a slipform operation.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Construction site west of Tucson in May, 1961, as works prepare to house the Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile. The dome will house the control center.

Fallout shelters

Updated

Dr. and Mrs. A. Russell Aanes check their civil defense rations as they start a two-week stay in an above-ground fallout shelter at KGUN-TV studios in October, 1961. The couple said they were "looking forward to catching up on long-delayed reading, napping and being away from the telephone." The TV station had a remote camera and would periodically monitor the couple inside.

Fallout shelters

Updated

A fallout shelter under construction behind a home in Tucson, ca. 1961.

Fallout shelters

Updated

John Stufflebean and family in their fallout shelter in Tucson in April, 1961.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

A Titan Missile section arrives at Davis-Monthan AFB in Nov. 1962.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan Missile lowered into silo, possibly near Three Points, Ariz., in Dec, 1962.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan Missile lowered into silo, possibly near Three Points, Ariz., in Dec, 1962.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan Missile lowered into silo, possibly near Three Points, Ariz., in Dec, 1962.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan II Complex 09- North Oracle Road, Pima County. August 15, 1971.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan LL Complex 09- Priority 1 safe locked down. August 15, 1971.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

The crew leader with his hand on the launch key at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

A airmen sleeping in quarters underground at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

The nuclear-tipped missile at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

Capt. Charles Harris, sitting front, and crew members discuss the situation during a drill at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

On-duty crew members at the ready during a drill at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977. P

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

The giant, hardened concrete sliding dome that covers the missile silo at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan II Complex 570-9

Updated

Off-duty crew members read, play cards at Titan II ICBM complex 570-9 south of Three Points, southwest of Tucson on Dec. 28, 1977.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Once underground, the dirt around the access portal at Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-4 has been excavated by Pima County, the property owner, for construction fill. The site is located near I-10 and AZ83.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

What was once part of the blast lock and the 250-foot long access tunnel to the missile silo has been partly excavated at the Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-3 near Empirita Road and I-10.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Inside the blast lock room looking toward the launch control center at the Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-3 near Empirita Road and I-10. The 6,000-pound blast doors are open, but the site is filling with dirt because of the partial excavation.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Wires remain in Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-3 in what would have been the tunnel to the missile silo from the blast lock - the central room one entered when entering the site from the access portal. The site is located near I-10 and Empirita Road.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Crista Simpson, owner of Crista's Totally Fit holds up a diagram of a Titan II Strategic Missile Site, similar to the one, 571-6, she lives atop near Amado.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Graffiti inside equipment at Titan II Strategic Missile Site 570-2, near Hermans Road and AZ86 near Robles Junction.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

For sale sign at Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-3 in 2006. The site is located near I-10 and Empirita Road.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

The top of the launch control center, once buried eight-feet underground, and other once buried parts at Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-4 are exposed after excavation by Pima County, the property owner, for construction fill dirt. The site is located near I-10 and AZ83.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Eric Neilson, owner of Titan II Strategic Missile Site 570-4 looks up into his home, built around the access portal in 2006. In 2002 he excavated and gained entrance to the launch control center.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Inside Titan II Strategic Missile Site 570-4's launch control center the man in the moon gazes into the four-member crews sleeping quarters.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

The logo for the 570th Strategic Missile Wing survived being buried for at least 15 years on a 6,000-pound blast door at Titan II Strategic Missile Site 570-4. Despite tons of debris filling the 35-foot deep access portal, when owner Eric Neilson excavated the site in 2002 the door opened up with just a bit of encouragement.

Titan Missile sites around Tucson

Updated

Titan II Strategic Missile Site 571-6 in Amado is home to Crista's Totally Fit fitness center in 2006. Crista Simpson, owner of the center who leases the property, uses one of the IRCS antenna pads for a picnic spot. She also uses one of the refueling pads to supply water to area wildlife.

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

An escape hatch inside the launch control center within a Titan MIssile complex for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

The blast door protecting the launch control center still work inside a Titan MIssile complex for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

Peeling lead paint on the wall of a Titan Missile complex for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

Property owner Rick Ellis passes through the junction between the launch control center and crew access portal at a deacivated Titan Missile complex for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

Ladders lashed together are the only way to the crew entrance nearly 100-feet underground at a 12-acre Titan Missile complex for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019

Titan Missile complex for sale

Updated

Demotion crews imploded the passageway from the the launch control center to missile silo after the Titan Missile complex was deactivated in the 1980s. The 12-acre plot is for sale along SR 79 about 10 miles north of Oracle Junction, Ariz., on Nov. 8, 2019