When a cow-printed van pulls into the parking lot of Santa Rita Park those scattered across the park assemble in front of it, knowing they’ll get hygiene items, water, clothing and maybe even a hot meal.

On Saturdays, Community on Wheels — or COW — hands out supplies at the park, a hotspot for the homeless population, partially due to its proximity to social service organizations and its accessible near-downtown location.

But on Jan. 21, COW and other local advocacy groups provided an additional resource: bright yellow signs that read “This is a constitutionally protected dwelling.” The signs were to be placed on tents or makeshift shelters that have been built in the park in anticipation of a displacement effort.

The warning comes after advocates say an internal city email indicated it plans to clear out Santa Rita Park’s homeless population ahead of the Gem, Mineral & Fossil Showcase, slated to begin this weekend.

On Jan. 17, COW, Community Care Tucson and the People’s Defense Initiative sued the city to halt enforcement of ordinances that ban residing in parks after hours.

The groups protested at Tuesday’s City Council meeting, telling members their concerns and raising signs reading “Stop the sweeps.”

City Attorney Mike Rankin said the allegation that a sweep of the park is planned because of the gem show is “demonstrably false.” But the park’s inhabitants will still have to vacate the park due to the city’s new encampment protocol.

Homeless advocate Victoria DeVasto addresses the Tucson City Council on Jan. 24.

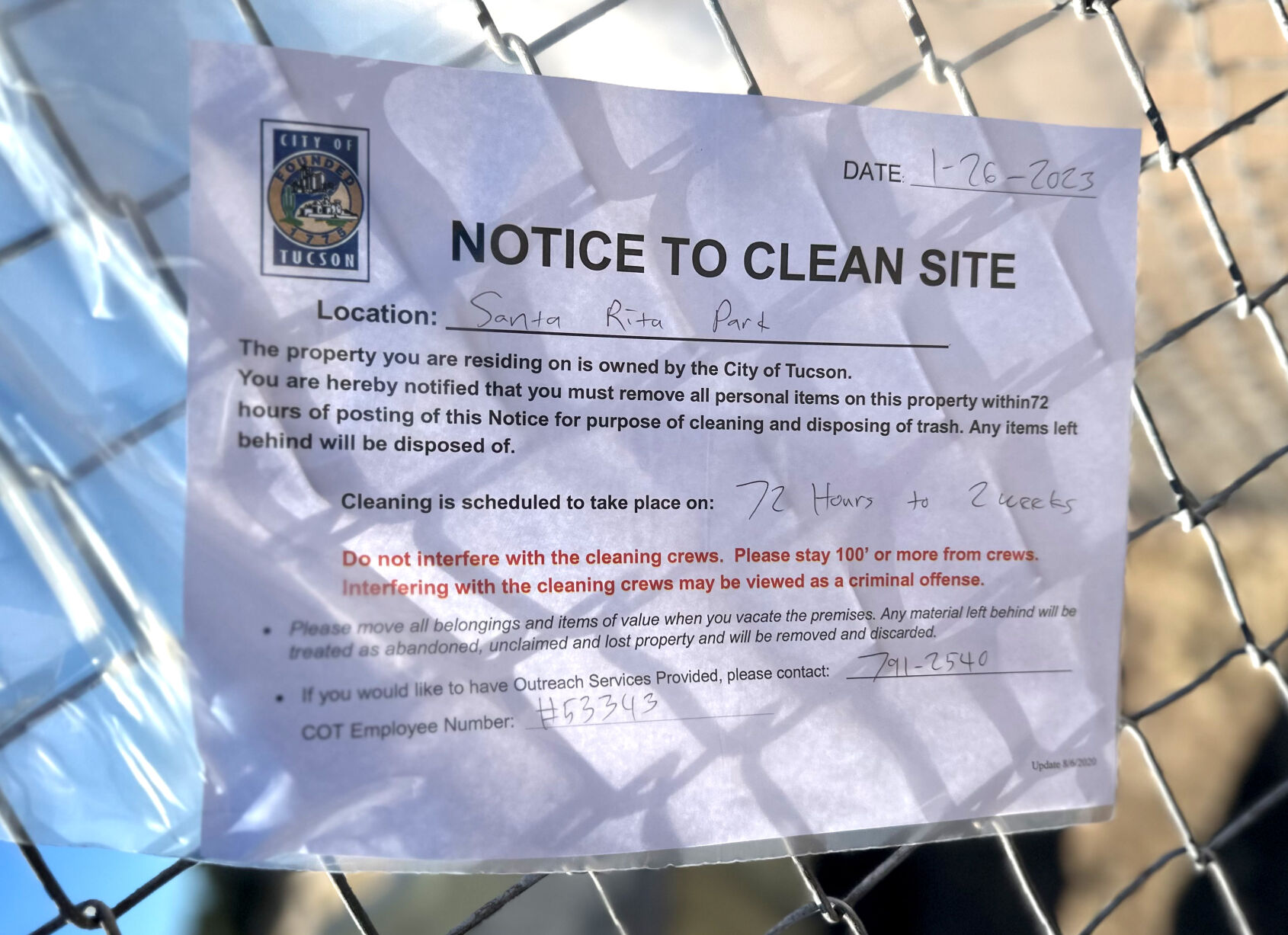

A Notice to Clean Site posted by Tucson city workers at Santa Rita Park.

New encampment protocol

On Thursday, notices were placed throughout Santa Rita Park warning people living there that they have 72 hours to remove all personal items from the park “for purpose of cleaning and disposing of trash” and that “Any items left behind will be disposed of.” The signs also warn that interfering with cleaning crews “may be viewed as a criminal offense.” The notices list the number to a city resource line.

In October, the city launched a new reporting tool for the public to report homeless encampments. Based on the danger the reported encampments pose to the public, inhabitants are either allowed to stay after cleanup or forced to leave within 72 hours. The notices posted at Santa Rita are in response to the new encampment protocol, the city said.

While saying he was limited on what he could say due to the pending litigation, Rankin said in an email to the Star: “Outreach at Santa Rita Park has been ongoing for years with many community partners. It includes connecting persons in the park with an array of social service organizations and attempting to assist the individuals that are unhoused obtain permanent stable housing.”

While sitting at a picnic table in the park on Thursday, Daniel Delgado said he’s not sure where he’s going to stay throughout the day now. He tries to sleep in alleyways to avoid being cited for sleeping at the park, but has been part of the park’s homeless community for about five years.

With the signage now warning him he’ll have to leave his daytime dwelling spot, he said, “I just gotta deal with it. Take it day by day.”

The need for shelter

Tucson’s Mayor and Council approved a master plan for Santa Rita Park in August that includes nearly $3 million in renovations as part of the $225 million Proposition 407 bond package voters approved in 2018. At the time the council approved the master plan, the same group of protesters took to City Council to denounce the renovations, foreseeing potential displacement of the park’s homeless population.

However, construction at the park isn’t set to begin for another year, according to the city. The notices provided are part of the “Tier 3” activation of the encampment protocol when a location is deemed “high problem” and exhibits “Violence and crime towards the surrounding community, the encampment inhabitants themselves, and many environmental hazards,” according to the city’s reporting tool.

According to the protocol, the city will call out enforcement to “address the criminal behavior, outreach will be offered, and clean up will be done by Environmental Services after the 72 hours vacate notice is posted.” Out of 2,943 encampments reported across Tucson, 155 have been determined to be Tier 3 sites, a city memo shows.

Rosie Portillo, who lives across the street from Santa Rita Park, said she’s reported the encampments at the park. Trash and drug paraphernalia frequently litter her front yard, she’s seen fighting and drug use and saw a man overdose at the park, Portillo said.

She discourages her two young kids from playing outside over fear for their safety, Portillo said.

“I would like to see more enforcement of having the people that are wanting to stay after 10:30 (when the park closes) just go ahead and head out, finding a different place,” she said. “I don’t know what that place would be. But that’s why the resources are out there.”

Tucson’s approach to addressing homelessness is a housing-first model that provides shelter without barriers to access. The city does acknowledge, however: “A shortage of and lack of formal coordination among outreach and housing navigator services contributes to long periods of time spent homeless before making contact with the homeless response system,” according to the city’s website on the local homelessness crisis.

Two homeless men go through carts of belongings near the south baseball diamond at Santa Rita Park.

Tucson doesn’t have enough resources to adequately handle its homelessness crisis, says the lawsuit filed against the city by the advocates for Santa Rita Park’s homeless population.

According to the complaint, there are about 3,000 people experiencing homelessness throughout the city and 859 emergency shelter beds. That’s based on estimates from the Pima County Homeless Management Information System, a database for local social service providers.

Displacing the park’s inhabitants, the complaint says, would violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment by forcing people out without alternative shelter options and the Fourteenth Amendment right to due process by discarding homeless people’s belongings without proper notice or temporarily holding the property to give owners’ a chance to retrieve it.

The plaintiffs are asking the court to stop the city from enforcing its anti-camping and after-hours ordinances that prohibit people from being in the city’s park from 10:30 p.m. to 6 a.m.

“The only numbers that matter to me, for purposes of this lawsuit, are do you have at least the same number of beds as there are predicted unsheltered individuals?” said Billy Peard, a paralegal working on the case. “If the answer is no, it doesn’t matter to me how many resources you’re providing … our position is that you cannot cite people for quality of life offenses in parks.”

‘Triage like an emergency room’

Tom Litwicki, the Chief Executive Officer for Old Pueblo Community Services, a nonprofit with the mission to end homelessness in Pima County, said the organization has 150 low-barrier shelter beds.

“The bottom line is that we have a third or so, maybe, of what’s needed, and so you just have to triage like an emergency room,” Litwicki said of the region’s homeless shelter capacity. “We’ve normalized the idea that I should drive by people that the layman can tell probably hasn’t cleaned up in a year, seems to be in a psychotic episode, and they’re just wandering the streets dying. It’s shocking.”

Nearly a week before the protest at City Council, COW member Victoria DeVasto said she stood over a homeless man who had died at Santa Rita Park due to exposure when temperatures dipped below freezing. The Tucson Police Department confirmed an “unresponsive male” was located at the park and that “it looks to be a medical issue, and no foul play was noted.”

Community on Wheels outreach at Santa Rita Park on Saturday, Jan. 21.

And while the resounding message from the protest at City Council was to “stop the sweeps” at homeless encampments, Tucson Police have previously denied that they conduct “sweeps” of encampments that result in an area-wide forced evacuation.

Instead, displacement often takes place on an individual level. Many of the homeless people residing at Santa Rita Park allege they’ve been woken up in the early morning hours by TPD or city staff and told to leave the park or given citations for illegally sleeping there.

Several unsheltered individuals provided affidavits of their experiences for the lawsuit against the city.

One man said that about 3 a.m. on Jan. 20, “Tucson Police approached me and kicked me out of Santa Rita Park. They did not offer me any services. Gospel Rescue Mission refused me a bed. They threatened me with citation, but cited other people in the park.”

Another man, who said he’s been homeless for 3 and a half years, wrote: “I was awakened and cited for camping at the park and had nowhere to go. As I nearly froze, I then was told as they threw my belonging away. I’ve seen the police do this to myself and others. I suffer from PTSD, depression, and anxiety and suffer from this last (incident) and I’m very very extremely upset and affected by it.”

When asked about the citations issued at Santa Rita, or how a Tier 3 response in the park would work, the Police Department said only that it couldn’t comment on pending litigation.

Anyia "Duchess" Butler, who lives in one of the city's parks, speaks during a Tucson City Council meeting on Jan. 24.

Plan in the works

Litwicki from Old Pueblo Community Services estimates up to 80% of chronically homeless individuals live with significant mental or physical disabilities compounded by poverty, and that the region’s current homelessness crisis is “the worst it’s ever been.”

“I think one thing that is critical to ever getting anywhere around homelessness is having a community-wide plan and strategy with real benchmarks,” he said.

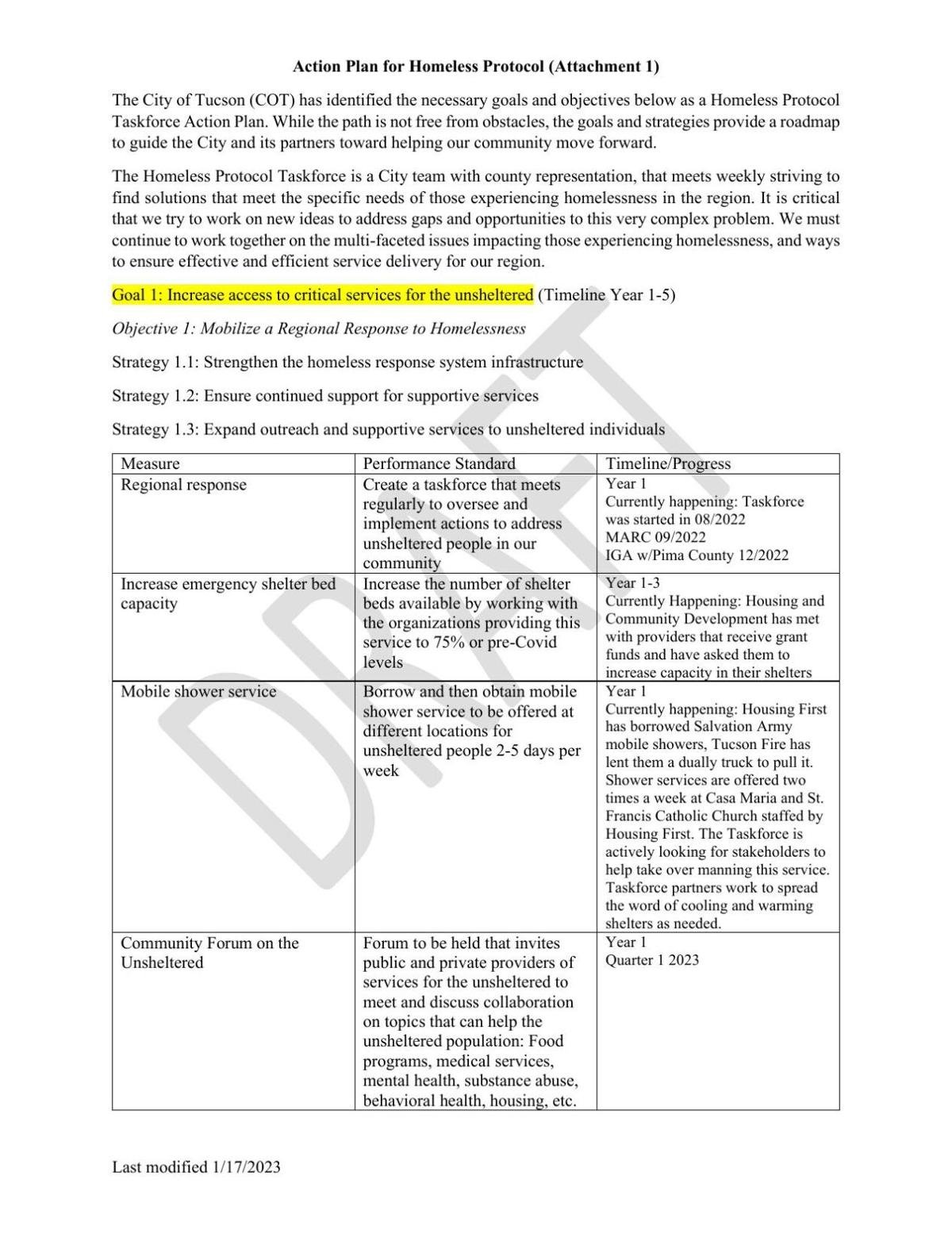

Pima County and Tucson have collaborated to create a homelessness task force that meets weekly, and at Tuesday’s City Council meeting, the leaders of city housing and homeless outreach departments shared a draft version of a five-year plan.

The plan has four objectives, the first being to “Increase access to critical services for the unsheltered.” The city has purchased several hotels to use as low barrier housing, and has started a mobile shower program that operates twice a week.

The other outlined goals include reducing “the impact of unsheltered individuals on the community,” creating “a data base to track integrated response” and “continuing to seek housing for unsheltered Tucsonans.”

“We want to make sure that we are supporting unsheltered people to become permanently housed, and we need to do something different than has been done for decades past,” Mayor Regina Romero said at Tuesday’s meeting. “This is only part of the solution to solve the issues of the unsheltered and the issues that residents and businesses have in terms of being able to deal with unsheltered homelessness in the city of Tucson.”

At the call to the audience portion of the council meeting, which took place after council members discussed the draft plan, DeVasto told council members more urgency is needed.

“We need emergency shelter in mass now. Alternative shelters and new strategies need to be implemented now,” she said, later adding, “How many people will die waiting for critical services in one to five years? You will be spending millions of dollars on other projects, allocate funds here now.”

The Tucson nonprofit I Am You 360 broke ground in March on its small home village for youth transitioning out of foster care. The foundations have been laid and walls built for six of the 10 buildings and work on the final four is underway. Video by Caitlin Schmidt / Arizona Daily Star.