At a University of Arizona forum last month, Law School Dean Marc Miller pressed the guest speakers on the issue of the moment.

Will the events of Oct. 7 in Israel lead to any change in First Amendment doctrine or free-speech policy on campus?

The issue was urgent when Miller asked the question Nov. 15. Two professors in the UA's College of Education had just been suspended after making ill-informed statements on the Israel-Hamas conflict in an early-education class, and having them revealed on Twitter.

In April, a crowd marched on the University of Arizona campus to counter a near-by anti-abortion display.

In the days after the forum, students staged sit-ins at the College of Education to protest the suspensions. Two weeks later, those professors were reinstated but not allowed to teach that class anymore.

At the same time, unknown to people outside the law school, an Israeli-American law professor was facing consequences for statements he made in class countering criticisms of Israel.

And then came this week. During a congressional hearing, the presidents of Harvard, MIT and the University of Pennsylvania equivocated about whether statements calling for genocide violate their schools' codes of conduct. It drew outrage from members of Congress and forced the presidents to backtrack the next day.

But when the experts in Tucson answered Miller's question about whether the war over there changes First Amendment doctrine or policy on campuses over here, they answered, essentially, "No."

Tim Steller, Metro columnist for the Arizona Daily Star.

"The short answer is it doesn’t change the basic doctrine," said former UA Law School Dean Toni Massaro, a First Amendment expert.

Eugene Volokh, a UCLA law professor and fellow First Amendment expert, said of campus discussion of the conflict: "This is an issue that need to be freely debated, and I don’t think the courts will say 'No, no no, the defense of Hamas is a completely different thing.' "

Not to mention, he noted, Arizona has strong and specific protections for such speech on campus — thanks in part to the Goldwater Institute and legislative Republicans.

A warning letter

Business law Prof. Barak Orbach didn't attend the Nov. 15 forum, but the issues discussed, of free speech, hate speech and academic freedom, were haunting his classroom at the time.

Orbach is originally from Israel, lost family members in the Holocaust, and is a veteran of the Israeli Defense Forces. He's taught at the University of Arizona for two decades.

"I've lived in the United States for 25 years,' he told me. "I’ve never thought about antisemitism until Oct. 7."

In the aftermath of that horrific attack, before Israeli forces entered Gaza, Orbach began feeling antisemitism's sting, he said. In unexpected conversations with students and colleagues, he heard stereotyping of Jews and blaming Israelis for their victimization, he said. There was little sympathy offered.

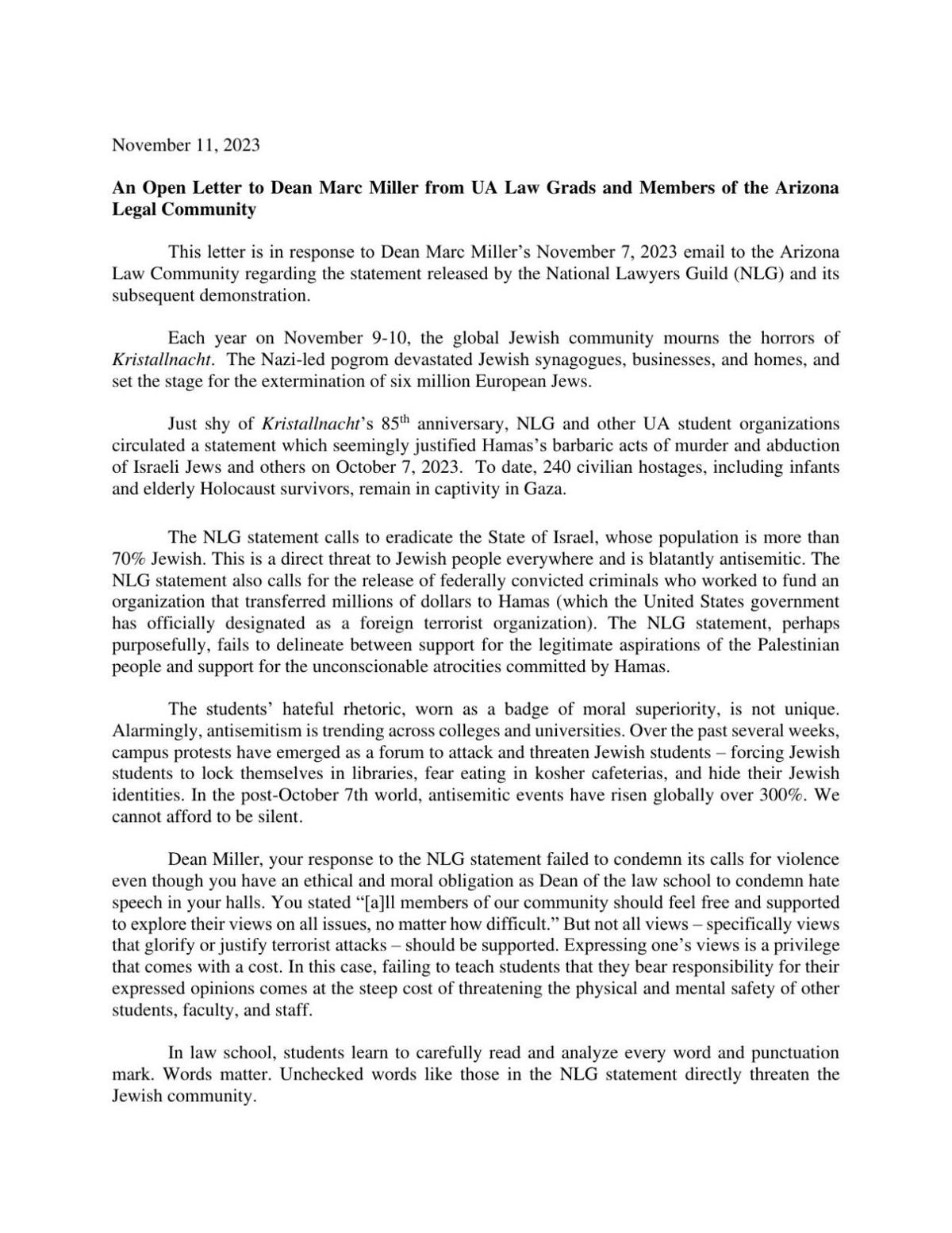

Then, on Nov. 6, the UA chapter of the National Lawyers Guild put out a fiery anti-Israel letter justifying "resistance" to the country's "settler colonial project."

Orbach was shocked by the vehement letter he considered antisemitic and by the tepid response to it from Miller, the law school dean. Miller wrote in a subsequent email, "Speech and protests are protected by the First Amendment, but specific threats and targeted harassment are not."

"Our students send horrible antisemitic statements," Orbach said. "The university refuses to denounce it as antisemitic."

In his classes the next day, Orbach said, he denounced the National Lawyers Guild letter, discussed his experience in the IDF, and he mentioned a Nov. 1 letter from dozens of big law firms. That letter warned law school deans that they were seeing antisemitism on campus and, in a roundabout way, suggested they wouldn't hire students engaged in it or maybe even from law schools where it was allowed to flourish.

You had to read between the lines to catch that warning, but some students apparently felt that Orbach was threatening to sabotage their careers over their opinions on Israel. Orbach says that wasn't his intent, and he doesn't know how many students complained.

The law school ended up allowing his students to attend Orbach's classes remotely if they wished and gave his students the right to choose a pass-fail option rather than be graded by him.

"Surely I was upset, but I was left in the position that I see such a letter (the National Lawyers Guild letter) and the University doesn’t protect me," he said.

"Nothing remotely like that would be tolerated if it were said about people of color, about the LGBTQ community, about women," he said. "About Jews it’s tolerated, because 'It’s complicated.' "

Perceived double standard

If you talk with Leila Hudson, an associate professor of Middle East Studies, you'll hear echoes of Orbach's arguments, but from a different direction. Hudson, a Palestinian-American faculty member and the chair of the UA Faculty Senate, sees room for a stronger code of conduct and calls out what she sees as double standards.

Conservatives who previously advocated for free-speech protections on campus in order to defend right-wing speech are less committed to the principle when it comes to defending people's right to defend Palestinians, she said.

Indeed, at a legislative hearing Nov. 27, legislators condemned what they called left-wing "indoctrination" by faculty. They also gave a friendly response to a witness who called for the suspension of student groups whom he considers pro-terrorist, as well as the deportation of pro-terrorist students, and the banning of "potentially disruptive events" on campus.

"We see it, and we're with you," Sen. Anthony Kern said in response.

Said Hudson: "I think they’re willing to make an exception to First Amendment rights in order to try to quash and cancel pro-Palestinian speech and pro-ceasefire speech, and a variety of critiques of the Israeli government."

In particular, she said, people have deployed an "expansive" definition of antisemitism to try to quell criticism of Israel's policies and of Zionism more generally. She cited House Resolution 894, which condemns antisemitism and states that "anti-Zionism is antisemitism."

"The legislation of meaning, and the use of that legislation to silence in the name of fighting hate, is a pretty slippery slope," she said.

Hudson put these concepts into a Dec. 1 letter to all UA faculty that raised protests. The main sticking points were these sentences:

"It is important to note that pro-Palestinian sentiments and expressions, calls for a ceasefire in Gaza or an end to US unconditional support for Israel, allegations of genocide, terrorism, war crimes, or critiques of any ideology, government, non-state actor, or state policy or practice are protected speech.

"Accusations that the above are, in and of themselves, essentially pro-Hamas, antisemitic, genocidal, or terroristic are problematic and potentially defamatory and have a chilling effect on free expression."

The idea that non-Jews get to determine what Jews feel is antisemitic bothered some faculty, including Orbach and a group of five law faculty who sent a letter Friday protesting Hudson's statements to UA Pres. Robert Robbins and the Arizona Board of Regents. So did the vague reference to defamation, which suggested that people who call Hudson or others "antisemitic" could be subject to a lawsuit.

But in conversation with me, she defended the idea, saying that hypothetically and in the right circumstances, such a lawsuit could be justified.

"I am ready, when and if someone calls me as an anti-Zionist, an antisemite, I’m ready to challenge that statement and have it looked at in light of the defamation standards," she said.

"As a Palestinian, we would be getting into really weird territory, that in order to be a member of respectable society, I can’t criticize the political movement that has killed my family members, dispossessed us, and continues to advocate for that state of affairs."

Free speech protected

This kind of speech may not be what Arizona's GOP Legislature had in mind when it adopted the Goldwater Institute's model legislation for free speech on campus and passed it into law in 2016 and 2018.

At the time, most of the support for the bills came from Republicans worried that conservative speech was being suppressed on campus. But now, the same language is protecting pro-Palestinian speech.

"It is not the proper role of an institution of higher education to shield individuals from speech protected by the First Amendment, including, without limitation, ideas and opinions that may be unwelcome, disagreeable or deeply offensive," says one of the paragraphs of those laws.

The laws also prohibit "free-speech zones" from being established on campus, defining the whole campus as a free-speech zone.

In fact, when I asked Interim Provost Ron Marx the question members of Congress asked university presidents last week, he gave a similar answer to those they offered.

"If there’s a clear and present threat to a specific group, that would violate the tenets of free speech on our campus," he said. "As noxious as it is, a call for genocide, when it’s an abstract call, is not actionable."

So, for people on campus, the question is not whether you can express your opinion about the Israel-Hamas conflict and all the associated issues, or other topics. You can. Neither the Oct. 7 attack nor any subsequent actions have changed that, and they shouldn't, in my mind.

And university administrations are limited in how much they can restrict offensive or even hateful speech. Both Orbach and Hudson think the university can do more in this regard, but I don't think it's a good idea. The Goldwater Institute and GOP got that right.

The bigger question is whether, when and how you should speak. After all, you don't have to take a position on a hot issue that you might not know a lot about.

At the forum, Massaro called for humility in speaking and proportionality in response to others' mistakes.

"We are all so profoundly ignorant," she said, speaking broadly.

Yet, she added, "Universities should be safe places for us to learn by speaking without catastrophic consequences for our blinders and our blunders."